Tahar Rahim plays Mohamedou Ould Slahi, the title character in "The Mauritanian," a gripping new drama based on the memoir, "Guantánamo Diary." Slahi is said to have recruited and helped organize the 9/11 attacks and is being detained in Guantanamo Bay without charges. He comes to be represented by Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), who hopes to prove the U.S. government lacks evidence to detain him. Meanwhile, Lt. Colonel Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch, who also produced) is hired to get Slahi the death penalty. How the case evolves, and what Hollander and Couch discover in the process, is compelling — even if that sometimes includes them reading and reacting to files.

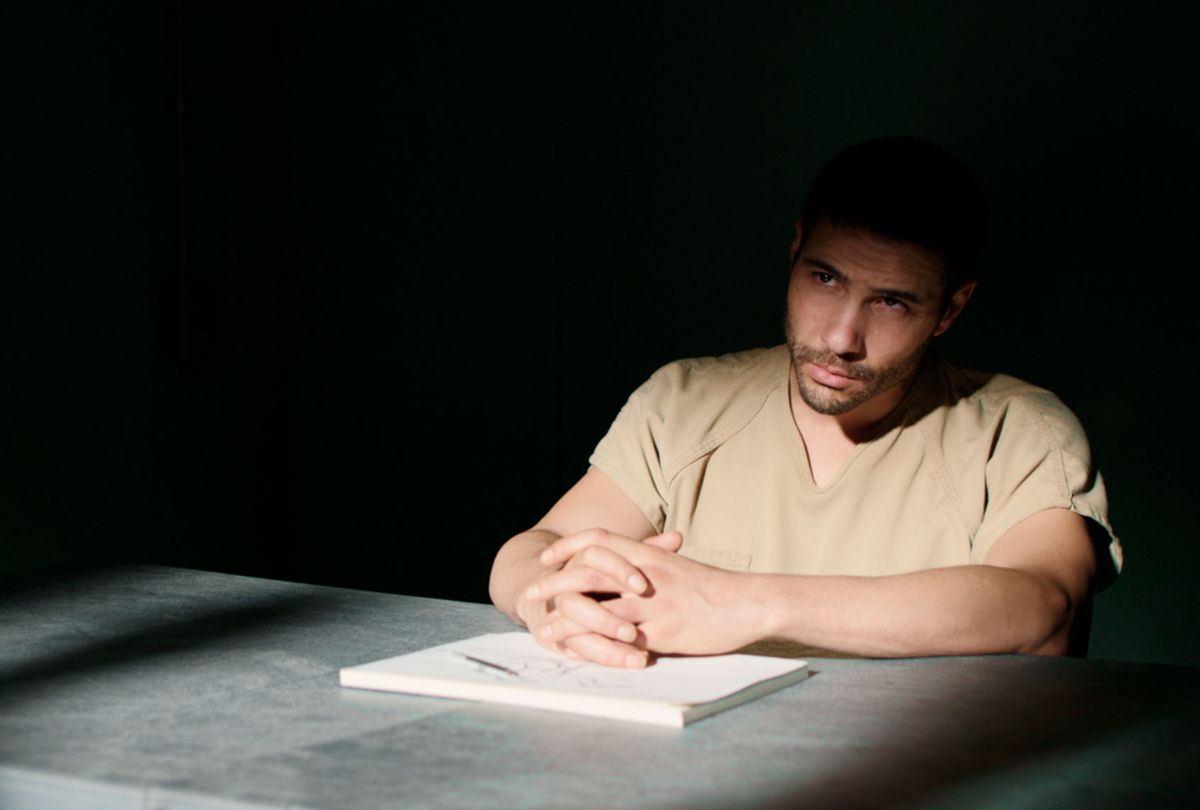

The real excitement in "The Mauritanian" is Rahim's committed performance. His moving turn will come as no surprise to anyone who saw the French actor in "A Prophet," another film where Rahim played an imprisoned character. Here, Rahim endures physical and psychological trauma as Mohamedou is tortured for a confession. He spends most of his screen time isolated and/or in chains. Rahim gives a very intense, and often internal performance as Mohamedou reacts to the forces around him. But he also gets impassioned in his speeches as he is fights for his life.

The actor, who was nominated for a Golden Globe for his performance, spoke with Salon about his film and playing the real-life Slahi.

How much of Slahi's story did you know when you were approached to play this role? Had you read his book?

[Making a "zero" with his thumb and index finger] Nothing!

Were you able to meet and discuss the part with Slahi, and what did he tell you that informed your performance?

I did my homework. I read the book. At some point I got to meet Slahi on Skype. And it was a beautiful, joyful moment. He was so full of life, so funny, ready to crack jokes all the time, playing music, talking about movies, it was unbelievable that he went to Guantanamo and lived through the horror.

At some point, I needed to do my job and I asked him questions about touchy topics. He changed. His face started to darken; the trauma would come to life in his face. It was almost hard for him to articulate, and I felt bad. Who am I to bring him back there? I stopped. I never did that again. I felt that the right way to get what I wanted was to talk with him and observe him and get to know each other. I felt I was meeting someone extraordinary. That doesn't happen often in life, so, I took advantage of it. My old friend Bob from Chicago would say, "If you don't have anything to say, you shut up and listen." And that's what I did.

Do you have concerns about playing Slahi, who was seen by many as a terrorist? Did you feel you could approach playing him as guilty or even ambiguously guilty, or not guilty? Did you recalibrate your performance?

When I read the script, and when I met him, it was obvious that he was innocent. The first act is made to make audience feel doubt, and if I fall into that trick, it's not going to be right. It was written and shot this way. All I had to be is convinced of my [character's] innocence. I needed to show the doubt, that he could mistrust his lawyers, and a system that put you in jail and tortured him with no charge. How can you trust the lawyers in front of you? I didn't think that I should show that I'm guilty or not.

Your exceptional work in "Un Prophet" surely made you a strong candidate for this role. What observations do you have about making prison movies?

[Laughs] I pick parts and good stories, which is what I'm trying to do. It was funny to think that my first big part in America would be a prison movie! But this film is so totally different from "A Prophet." This is a true story. I got interested by the depiction of his character regarding his background. It's rare to read parts like that. What I see from Middle East characters are stereotypical. I never wanted to play them, so I've said "no" many times to Hollywood and Europe. But this time, you could take the part and put it in another context, and the story would still work. So there so many layers to play and emotions to convey.

The film requires some real physical work from you — not just your body's transformation, but also your body language. Can you talk about how you approached the character who is mostly confined, chained, and disoriented?

When I picked the part, I knew there would be a lot of challenges. Thank God, I've never been tortured before, and I didn't know how to do it. The way I found to do him justice and be convincing was getting as close as possible to get to the real conditions as Mohamedou. I asked the props department to bring me real shackles, to make the cell as cold as possible. I wanted to be waterboarded for real, force-fed. I lost 10-12 kilos in short amount of time. I wanted to experience what it feels like to be treated this way, so I don't have to sell something or create something out of the blue. I needed to feel physically what it was to be in those conditions. When I play feelings and emotions, I take what I've been through in my own life. I imagine some stuff and then I mix it and it feels like truth. But this was the other way around. Your emotions pop out here and there in drastic conditions. What I had to do was grab my emotions and let them lead me to some emotional states that I'd not experienced before. That felt like I was touching a sort of truth, and as an actor, that's what you seek.

What is your threshold for pain, how much suffering can you endure?

There was something odd — it was the first time I had gone this far physically. The more I would dive into, I wanted to go on and on, and it would never really stop in my mind. But I'm seeking truth, so when you feel like you're touching it from the tip of your finger, you want to go further and further and further, to a point that Kevin [Macdonald, the director] came to me. He was worried, and said, "You're doing well, and I believe in it." But I was like, "It's personal now. I need to go as deep as I can. Don't worry, I'm not going to hurt myself." And I did. The hallucination scene. I never took drugs before, I never got sick to the point to hallucinate. When we shot it, I was exhausted, and It was like I saw my own mom in the cell, it was very strange. I could do it just once then I literally collapsed. I laid down and said, "I can't do it twice."

What can you say about working with Jodie Foster? How did you develop your onscreen relationship with her? I'm assuming you both spoke in French!

I wanted to hear her speak in French, so I started to speak French, and she answered, and my coach stopped me, and said, "You're gonna play in English and you're going to speak French? Stop it now!" She speaks better French than I do.

We met at a read through and I have to say I was a bit intimidated. I grew up with her movies. I was nervous, but the way she behaves, her personality, relaxed me, and we talked about the parts and talked with Kevin. When we were on set it was magical. It was an honor to work with her. It was like a dance. The script was the choreography. When you get on set, you do your dance as it's supposed to be, but at some point, you want to improvise, and pace left or right, and she follows, and something happens. It brings you to a space where time and space are not the same, and this is what it means to be in the present. It's all about the trust you have for your partner.

What are your thoughts about Slahi's faith? He talks about God. He talks about forgiveness.

He has a great, great faith in God and that really helped him to get through this of course, and this extraordinary philosophy — to forgive folks who did bad things to you. I asked him, "Were you angry against God at some point?" And he said, "Yes, because I couldn't understand why I was here? Why was this happening to me?" He realized that forgiving people is a treat you give to yourself. By doing this you might have the power to change people's mind. And that's what happened with his captors. When they would torture him, he would ask them, "Why did you do this to yourself?" After years, they bonded and became friends. To have this power is incredible.

Are you someone who holds a grudge?

I do sometimes. I'm trying not to. His philosophy is a good direction to take in life. I feel like when you are angry at someone you're pretending it's all good, but in your head, you feel bad inside, and keep thinking over and over about it; and at the end of the day, you're the one who suffers. I have the will to be like that, but it's a long way.

Slahi talks about living in fear of the police but also believing that the law protects. Do you have any experiences with the law yourself?

In every job or groups, you have bad people and good people. I never had trouble with police in my life, or problems with justice. A man I used to see in my suburb, he would drink a lot, and one day he took a slice of pizza and didn't pay. He didn't have money. He did six months in jail for a slice of pizza.

Slahi lives in hope that he will see his family. What is your coping mechanism during periods of trouble?

I have family, and friends. That helps me when I have to face hard things in life. Even if bad things happen in the past, or future, there are still good people with the will to make the world a better place. I like to think about them.

"The Mauritanian" might position you for more work in Hollywood. Are you worried about being typecast?

Even before I worked in the business, I knew I never wanted to be typecast, or do the same part all the time. It wouldn't be interesting. I like to explore, and be surprised, and challenged as an actor. It was not an easy thing to do, because you build your career by saying "no" more than "yes." Sometimes it's scary. You say "no" three, four times in a row and people think I'm too picky, or that maybe I don't want work? It's risky, but you have to risk to reach your goal. My goal is to experience different things all the time, from playing a doctor to a gangster to a murderer to a lawyer. Acting is a bit like being an anthropologist. You have to be the devil's advocate. You get to know more of the human condition, and humanity, and it makes your more indulgent in your own life. It helps in your everyday life, when you talk to people, or to talk with your kids, or to be more indulgent when you talk with your neighbors, or friends. But with typecasting, actors must be risky enough to say no; producers to want to tell different stories; for writers, to depict characters from certain backgrounds differently, and not always have to justify a color a religion or something because the character has a certain name. I see Arab and Black cops, lawyers from different backgrounds. These are characters as well. Just tell their stories.

"The Mauritanian" premieres in select theaters nationwide on Friday, Feb. 12.

Shares