On Jan. 6, a violent mob invaded the U.S. Capitol, injuring more than 140 police officers and bludgeoning one officer to death. Their goal was to prevent a joint session of Congress from certifying Joe Biden's victory in the 2020 presidential election and to find, and possibly kidnap or murder, elected officials they held responsible for what they considered the theft of the election. Some have called the assault an attempted coup, others an act of insurrection. The attack has raised a question that has been repeatedly asked in the five years since Donald Trump began his ascent to the presidency: Are Trump and his followers fascist, and is Trumpism perhaps the most successful example of American fascism in the nation's history?

The problem with calling anyone or any movement fascist is that "fascism" is likely the slipperiest term in our political vocabulary. And there is the further problem that there has never been a large avowedly fascist movement in the United States. But if we look at the perpetrators of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol — with their Confederate flags, their claims to be religious warriors for Jesus, their beliefs that those opposing them were traitors — we see elements that have been common in descriptions of American fascism for a century. In the words of one commentator on the subject:

These organizations exploit the active and latent prejudices that the average American has against the non-white races on the one hand and against the Jewish people on the other. They make it possible for a creative rationalization to provide a cloak for group hatreds which can be objectified as true Christianity or true Americanism. In other words, they provide for a legitimizing of sadistic and demonical impulses of which, under normal circumstances they might be ashamed. To appeal to anti-Negro sentiment in many sections, communities and among many groups is a "natural" for the would-be demagogue. It is sure fire.

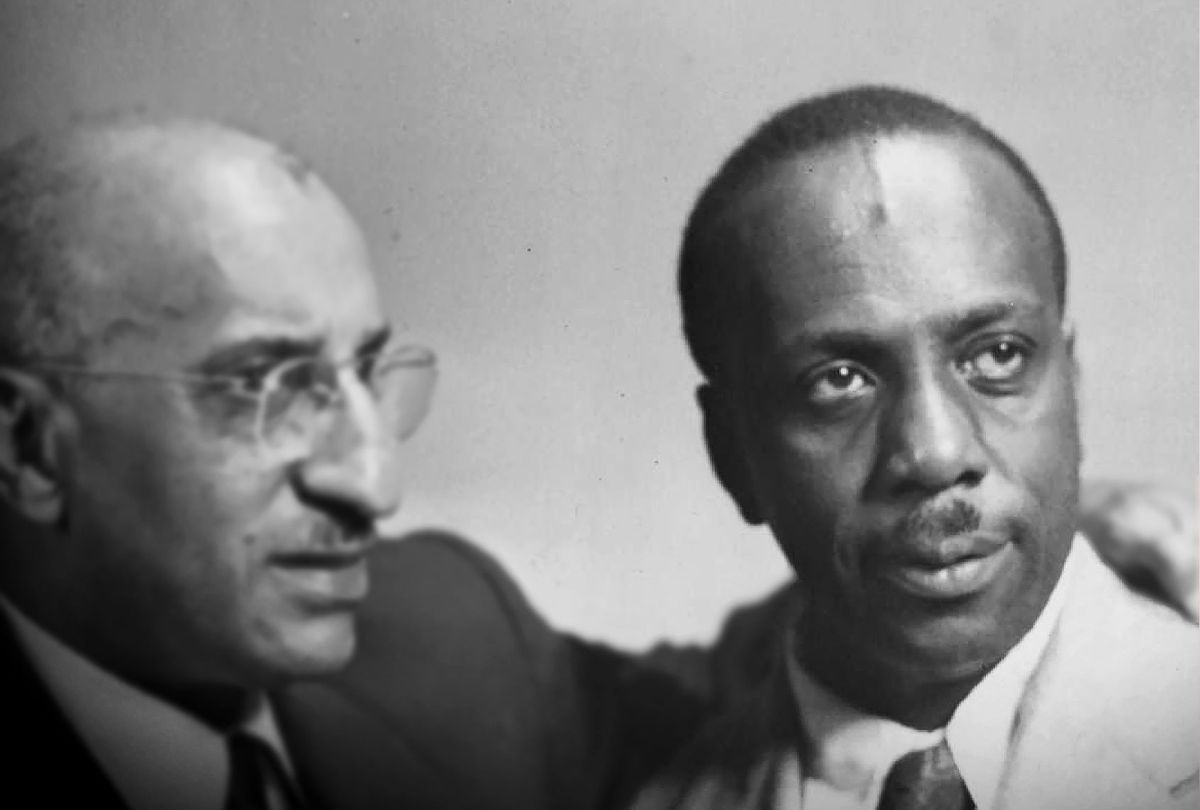

The word "Negro" is a likely giveaway, but this is not a reflection on recent events. It was written by the African American religious thinker, Howard Thurman (1899–1981), a pioneering advocate of radical nonviolence, an inspiration to the Black Freedom Struggle, a mentor to such civil rights pioneers as James Farmer, Pauli Murray and Martin Luther King Jr., and published in a 1946 essay titled "The Fascist Masquerade." The essay is one of Thurman's most urgent yet enduring political works. Its inspiration was Thurman's sense that the United States, shortly after the end of World War II, was at a crossroads. Either the post-war period would see the furthering of the tentative wartime gains by Black Americans for full citizenship, or it would see those aspirations crushed, as had happened so many times before, by a ferocious pushback by the maintainers and abetters of what Thurman called "the will to segregation."

Thurman, to be sure, was an optimist. In 1944 he left a comfortable position as dean of chapel at Howard University to co-found a small, fledgling congregation in San Francisco, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, one of the first churches in the U.S. intentionally organized on an interracial and interdenominational basis. At the same time, he was a realist. He wrote in 1943 that the war against Japan "has given excellent justification for the expression of the prejudices against non-white peoples just under the surface of the American consciousness." In his wartime travels he found "the picture is the same everywhere — sporadic outbursts of violence, meanness, murder, and bloodshed." Black Americans were angry, and many whites were furious that they were no longer hiding their anger. The United States had to choose between democracy and fascism, and for Thurman the outcome was uncertain. But he was sure that American fascism would hide behind a homegrown vocabulary drawn from a toxic and intolerant Christianity and ultra-Americanism, disguising their real beliefs and intents. This was the fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the key to the ideology of fascism was the belief in inequality, the belief that the world was invidiously divided between the haves and have-nots, those favored, whom the state would help, and those out of favor, to whom the state disclaimed and denied any responsibility. Fascism was a worldview that built upon all existing inequalities; whether of race, class, nationality or what have you, and consciously tried to exacerbate those differences. And that was how business elites and the common racial prejudices of most white Americans could find common ground in fascism.

By 1946 Thurman was very concerned by the growing strength of anti-union sentiment in post-war America. Among the fascist organizations he considered in detail in his essay was the now quite obscure Christian American Association. Based in Houston, it was a racist, anti-labor and anti-Semitic organization whose one lasting contribution to American history was to popularize the term "right to work" while working to help enact the nation's first such laws, banning the "closed" or union shop, in Arkansas and Florida, in 1944. (One reason for such laws, the organization stated, was so "white men and women" would not be forced to work with "black African apes.") Thurman thought the Christian American Association had the perfect name for an American fascist organization.

Another, much better-known group Thurman wrote about was the Ku Klux Klan, which some observers had labeled fascist even before Benito Mussolini seized power in Italy in 1922. The Klan, in its various incarnations, had an exceptional longevity whereas, as Thurman wrote, most "hate organizations spring up, flourish for a season, disappear, and reappear in another form." The organizational form of such groups was less important than their continuing appeal, he added, noting that "an important part of the menace of fascism is its property as a catalyst," how its appeal "crystallizes moods, attitudes, and fears already in solution."

Thurman's enduring insight was that was a mistake to see hate organizations like the Klan as somehow outside the political mainstream. They were merely the far edge of a society that tolerated inequalities of all kinds as part of its civic and political life. To counter hate organizations it was "no answer to say" that hate organizations represent "a false interpretation of Christianity" or America. They represented the church and the state only too well. Traditional Protestant Christianity, he thought, with its ironclad division between the saved and the damned, provided the template for all the invidious distinctions that underlined American racism and fascism. As for American democracy, in the gap between the soaring promises of the Declaration of Independence and the uglier realities was a space in which economic and social inequalities could fester and become accepted as natural or even essential parts of American society and religion. This allowed, Thurman wrote, "the various hate-inspired groups to establish squatter's rights" in our basic institutions.

What would Thurman have to say about Donald Trump and the Capitol insurrection? Such retrospective ventriloquizing is always dangerous, but it is fair to say that he would have been appalled, and would have been dismayed that for all the changes in the United States since 1946, the descendants of the Christian American Association are still engaged in a version of the same old Christian American fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the most pressing danger of the fascist masquerade was its protean quality, its myriad guises and disguises. It was all too easy to become inured to its prevalence. It is not enough to oppose the KKK or their latter-day descendants such as the Proud Boys. We must look to the ways inequalities between persons are tolerated in our society as a whole. We must look to ourselves, and examine the ways we tolerate inequalities of all kinds in our own lives and politics. Thurman argued that we must "rely upon the guarantee of God in whom all life and all of the great potentials of mind and spirit are grounded. Such a position establishes the infinite worth of all individuals and denies that for which fascism stands."

We may see this struggle in more secular terms than Thurman, and we may believe that implementing a society based on the "infinite worth of all individuals," where no one is a means to another person's ends, is a utopian dream. At the same time, we need to confront the reality that almost 75 years after Thurman wrote his essay, the fascist masquerade, with its facades, its lies, its true believers and silent supporters, and its chilling willingness to resort to violence, is still very much with us, and seems to be growing stronger, not weaker. And as Thurman wrote in 1946, in 2021 we still stand at a crossroads, and still face the same stark choice: Democracy or fascism.

Shares