Republican control over redistricting in key Southern states, along with Supreme Court decisions that gutted protections for voters of color, could result in historically unfair congressional maps after the next round of gerrymandering, according to a new report from the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School.

The redistricting that followed the 2010 census resulted in “some of the most gerrymandered and racially discriminatory maps” in history but the next cycle of redistricting could be even more fraught with abuse in Southern states, according to the report. Florida, Texas and North Carolina, all of which are expected to gain House seats following the 2020 census, as well as Georgia, pose the highest risk of producing maps that are racially discriminatory and favor Republicans.

The report cited a confluence of factors for the growing risk. The next round of redistricting will be the first since the Supreme Court in 2013 gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required states with a history of racial discrimination to receive advance clearance from the Justice Department before making any electoral changes. The court’s conservative majority later ruled in 2019 that federal courts had no jurisdiction to review partisan gerrymanders, which have been “heavily accomplished by discriminating against communities of color,” said Michael Li, the author of the report and senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program.

Single-party Republican control over the map-drawing process and rapidly changing demographics, coupled with the weakened protections, are likely to result in even more “unfair” maps in those states than the last round. “Invariably, communities of color would bear much of the brunt, facing outright discrimination in some places and being used as a convenient tool for achieving unfair partisan advantage in others,” the report said.

Li said that Southern Republicans often focus on race because “it’s really hard to gerrymander” without “using communities of color.”

“While last decade you saw Republicans pack Black voters in states like North Carolina into districts and try to justify it on the basis of complying with the Voting Rights Act,” he said, “the danger this decade is they will pack Black voters and Latino voters into districts and simply say they were discriminating against Democrats because the Supreme Court said that’s OK.”

Democratic groups argue that despite the Supreme Court’s decisions, there has been progress in forming nonpartisan or bipartisan commissions to take redistricting out of the hands of state legislatures.

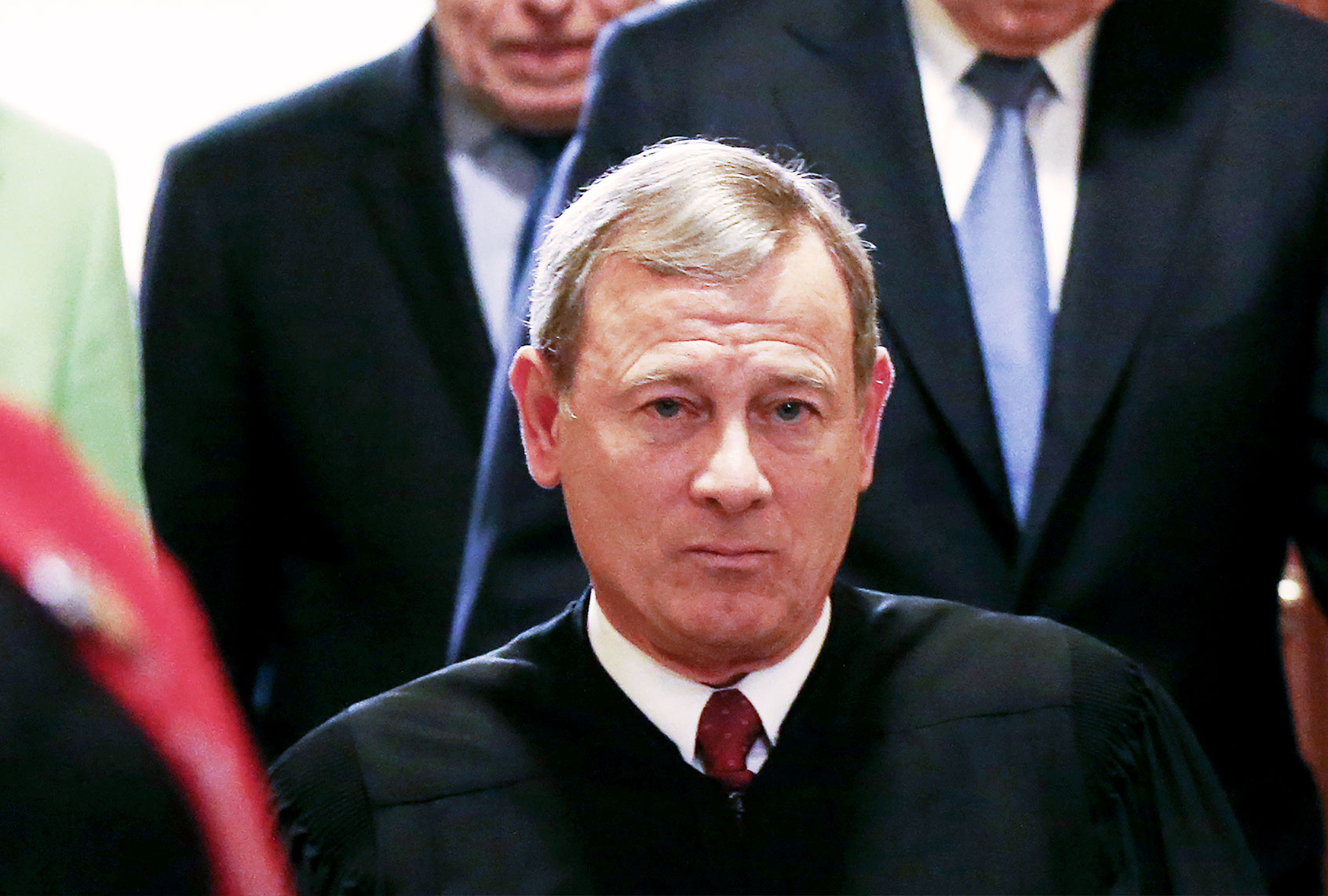

Under Chief Justice John Roberts, “there has been this sort of chipping away at voting rights, a lot of really frustrating decisions coming from the court,” Marina Jenkins, director of litigation and policy at the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, said in an interview. “That is sort of balanced, at the very least, by gains that have been made in a number of states in terms of changing who holds the pen on map-drawing.”

Though some states with past abuses have moved toward creating nonpartisan commissions for redistricting, the majority of House districts will be drawn under single-party control. Republicans have a massive edge over Democrats in terms of state legislative power: They hold control over 181 congressional districts while Democrats will determine the maps for just 49 seats. Single-party control is “by far the biggest predictor of redistricting abuses,” the Brennan Center report said.

Republicans have worked for years to carve up states to benefit the party using extensive demographic research that typically sought to dilute the voting power of Black residents. Files obtained from the computer of Thomas Hofeller, the late Republican gerrymandering guru, showed that the GOP in some states relied on spreadsheets breaking down neighborhoods by race to draw more friendly districts. But technological advances have birthed efforts like REDMAP, which helped the Republican Party pick up seats by carving out favorable districts using advanced software and terabytes of data. Improved data and technological advances have only increased the danger posed by single-party control since 2011, according to the Brennan Center report.

The 2011 redistricting cycle was one of the most extreme examples in history of how highly partisan gerrymanders allow lawmakers to choose their own voters, rather than the other way around, and allow the GOP to wield a disproportionate amount of power.

Republicans took over full control of redistricting in states like Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin on the strength of the 2010 Tea Party wave, allowing them to set up near-permanent majorities for the following decade. Republicans created maps that allowed them to win 10 of 13 House seats in North Carolina and 13 of 18 in Pennsylvania, even though they received roughly the same amount of votes statewide as Democrats did. The Brennan Center in 2016 found that gerrymandering in Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania alone was responsible for giving Republicans an additional 16 to 17 more seats in the House than they would have had with fair maps.

Democrats have tried to draw favorable maps as well, in states like New Jersey and Maryland, but have held control over far fewer states’ redistricting processes and have been far less aggressive with their gerrymandering efforts.

The increased media attention on gerrymandering may make some states reluctant to openly discriminate against communities of color, Jenkins said.

“There’s so much attention that states are going to have a really hard time conceiving maps that are worse than they are now,” she said. State lawmakers would be hard-pressed to “reduce the political power of communities of color,” she added.

Since the 2011 round of redistricting, voters in Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, Colorado, New York and Utah have approved reforms aimed at creating more fair maps. Colorado and Michigan both created independent commissions that will oversee the new maps. Virginia created a bipartisan commission. New York and Utah created advisory commissions that will recommend maps to state legislatures. But it remains unclear whether those two states will comply with the commissions’ recommendations, while Republicans in states like Michigan have repeatedly sued to try to strike down the new system.

Other states, like Minnesota, have adopted fairer maps as a result of a divided government, giving either party veto power over any potential partisan abuses. But Republicans continue to hold single-party control across the South from Florida to Texas and are more likely than ever to draw unfair maps as a result of changing racial demographics that threaten their hold on power and reduced protections for communities of color.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in the 2019 Rucho v. Common Cause case overturned lower court decisions and effectively prohibited federal courts from weighing in on partisan gerrymanders, after those courts struck down several gerrymanders in 2016.

That decision followed the 2013 ruling in the Shelby County v. Holder case that ended the pre-clearance requirement for 16 mostly Southern states that had previously been required to prove that their maps were not discriminatory. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority ruled that the formula used to determine which states were covered by the requirement was outdated, even though it had been used to reject a gerrymander in Texas just one year earlier.

The gutting of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act could also increase the risk that states “potentially game the timing of redistricting,” according to the Brennan Center report.

“In the past, states had an incentive to complete redistricting expeditiously to allow enough time for the back-and-forth of preclearance review,” the report said. “Now, states previously subject to Section 5 may choose to delay completing redistricting to limit time for litigating any challenges brought under other laws.”

The risk of delayed maps is even higher this year after the Census Bureau announced that the data needed for redistricting would not be ready by the usual deadline of April 1 as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, pushing the new date back to Sept. 30. Some states will have to change their laws to avoid overshooting deadlines related to redistricting while Virginia, which will hold legislative elections in 2021, likely won’t have enough time to draw new maps before the election. Many states will likely be forced to hold special legislative sessions to draw maps, which the Brennan Center report argued “significantly increases the risk of abuses” because these sessions are often short, “reducing the opportunity for hearings and effective public oversight.” Delayed maps also mean that courts will have less time to review challenges to new maps.

Jenkins said the delay was “absolutely a concern” but was optimistic that states can begin their normal redistricting process and hold hearings in advance of the data release.

“Hopefully, the energy and engagement from advocacy communities will put the heat on states to actually do that,” she said. “Litigation or petitioning courts for extensions of time, I think, is on the table. This is a crunch, but I think there is lots of time for the appropriate planning, to make sure that redistricting doesn’t have to be done in a manic short timeframe.”

Li predicted that some states may try to use data sets like the American Community Survey to draw preliminary maps without public feedback, and only release the final maps once the Census data is in.

“The reality is lots of people are already looking at maps,” he said. “They’re already trying to figure in Texas where to stick congressional districts, how to gain extra seats or protect seats. People are already looking at maps behind the scenes.”

Jenkins said that it is to be expected that “there are bad actors who are going to try to game the system.”

“That was true before, as it is true now,” she said. “I don’t think those bad actors are different from the bad actors who were expected to behave poorly even before the delay was announced. I understand the concerns and I share them. But it is not something that we are not fighting. We were already prepared for that.”

The delays also create a lot of unknowns about upcoming election cycles. Courts may block maps from going into effect or decide that legal challenges come too late, Li said. They could order states to redraw maps or order that special elections be held at a different time.

There are other changes that states could make to further dilute the voting power of communities of color. The Census Bureau was embroiled in a years-long legal battle after the Trump administration tried to include a citizenship question that voting rights advocates worried would result in an attempt to exclude non-citizens from the count, which would likely disproportionately affect Latinos. Though the Trump administration ultimately dropped the plan — which had been pushed by Hofeller — after the Supreme Court ruled that it had lied about the true reason for the addition, the Brennan Center report warns that the next round of redistricting could also restart the fight over whether states can draw legislative or local government districts based on the adult citizen population rather than the total population.

Such an effort would almost certainly be challenged in court. The Supreme Court in 2016 rejected a case brought by conservative activists which sought to require states to base maps only on the adult citizen population, but “left unresolved the question of whether it is constitutional for states to voluntarily use adult citizen populations as the basis for drawing districts,” the report said.

“The Missouri constitution was changed to add ambiguous language that potentially could open the door to draw legislative districts on the basis of adult citizens rather than total population,” Li said, although it’s unclear whether Missouri officials will attempt to do that. Other states may also try to change their state constitutions, or may limit such efforts to local government and county positions rather than legislative seats.

The report highlighted the particularly high risk of gerrymandering abuse in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas.

Though a 2010 constitutional amendment barring partisan gerrymandering and various state supreme court decisions have “created some guardrails that could help constrain the most blatant abuses,” the report said, the appointment of new conservative justices to the U.S. Supreme Court has raised questions about “how vigorously the court will enforce those limits on gerrymandering in state law should Republicans decide again to aggressively gerrymander.”

Georgia, which just voted for a Democratic presidential candidate for the first time in 28 years and elected two Democratic senators for the first time in two decades, has seen its share of nonwhite voters grow quickly since the last round of redistricting, while white suburban voters also increasingly back Democrats.

“These two trends in tandem threaten Republicans’ hold on power, making it tempting to use their single-party control of the process to gerrymander maps to safeguard against change,” the report said. “And as in southern states in general, the existence of racially polarized voting means that the most efficient way to gerrymander is often to target communities of color.”

In North Carolina, Republicans still control the redistricting process because Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, plays no role. Though state courts struck down the state legislature’s previous gerrymander, “those decisions will not stop Republicans from again passing gerrymandered maps” though they will “provide voters with an avenue for redress,” the report said. But given the increasingly conservative makeup of the state Supreme Court, “it remains to be seen how vigorously the court will apply” those precedents.

Texas’ previous gerrymander also resulted in a years-long federal court battle, and the state’s rapidly changing demographics increasingly threaten once-safe Republican seats.

“A crucial question this decade will be whether Republicans try to aggressively maximize seats — at the risk of losing some of them by decade’s end due to political and demographic changes,” the report said, “or try to draw a smaller number of safe seats.”

Other high-risk states include Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina, which have not seen the same degree of demographic change or population growth but were also previously covered by Section 5 of the VRA and have single-party Republican control.

Though the report highlights concerns around potential gerrymandering abuses in the South, there have been some positive signs in changes to the redistricting process since the 2011 cycle. State courts in Pennsylvania and North Carolina struck down Republican-drawn maps in recent years, suggesting that these lawsuits could serve as a “model for other states’ efforts to ensure fair maps.” The Supreme Court’s decisions over the last decade to block blatantly racial gerrymanders as unconstitutional could also be used to target partisan gerrymanders that rely on race data. But Li said Congress must act to crack down on the potential for abuse.

Li pointed to H.R. 1, a sweeping pro-democracy bill that would expand voting rights and, among other things, ban partisan gerrymandering, strengthen protections for people of color and expedite judicial remedies.

He also pointed to the Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would renew Section 5 of the VRA and require states with a history of discrimination to once again seek approval of their maps from the Justice Department.

“Those are all things that could be done and have a huge impact on congressional redistricting,” he said.

Jenkins said the NRDC is “enthusiastic about the possibility of the Voting Rights Advancement Act passing this year” and is “very focused on the possibility of a federal statutory partisan gerrymandering ban from H.R. 1.” But she is also optimistic that there are already enough public engagement and resources to prevent the worst gerrymandering abuses.

Jessica Post, the president of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, shares that optimism.

“As the process gets underway this year, we’re going to scrutinize Republicans’ every move and use every tool at our disposal to fight for fair maps,” Post said in a statement to Salon, vowing that the mistakes of 2010 that led to electoral disaster for Democrats will not be repeated. “We know that Republicans will do whatever they can to rig these maps — unlike 10 years ago, we will have a comprehensive legal strategy and resources to fight back.”