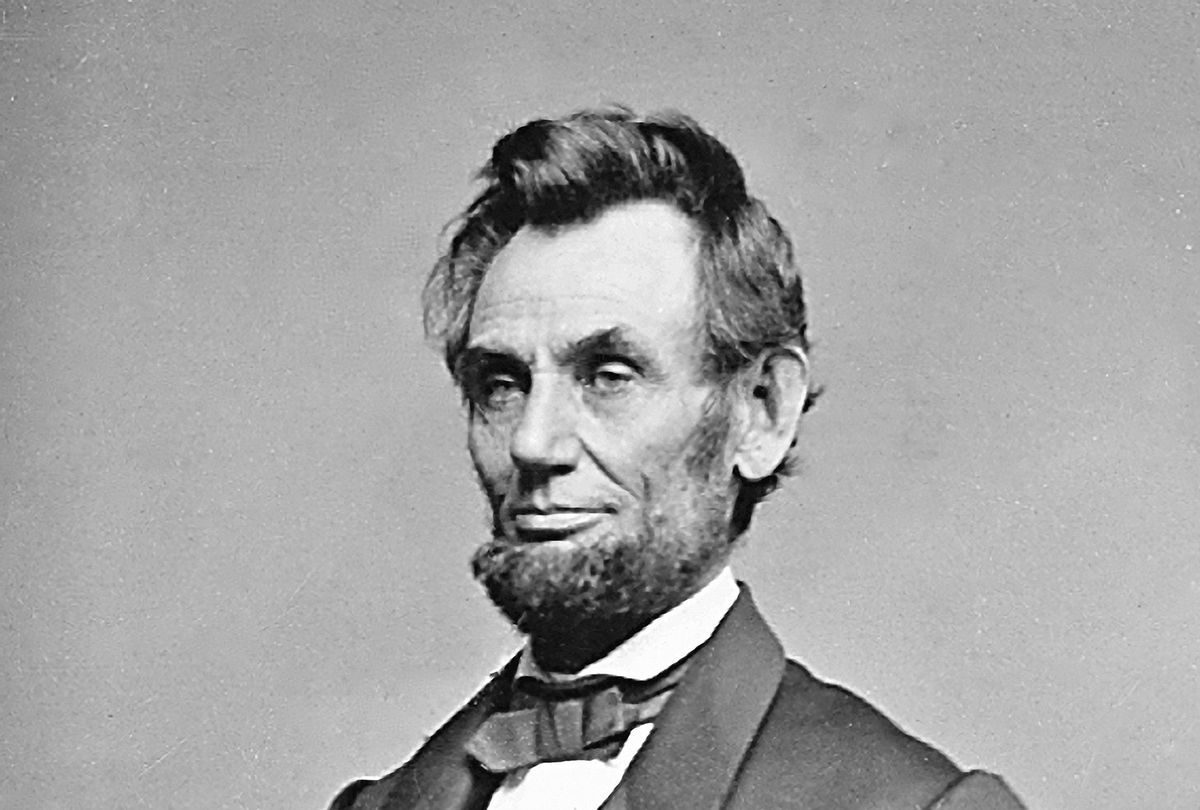

There is something incredibly charming about seeing talk show host Conan O'Brien deconstruct the genius of Abraham Lincoln — not Lincoln the president, but Lincoln the self-deprecating comedian.

This is one of the myriad pleasures derived from watching CNN's new six-part miniseries "Lincoln: Divided We Stand," which aired its first episode on Valentine's Day. It is a cliché to point out that Lincoln was one of America's greatest presidents, if not the greatest. He freed enslaved people, won the Civil War and was ahead of his time on economic issues. Yet apart from being a great president, Lincoln was also a fascinating man. It is this aspect of America's 16th president that is captivatingly brought to the fore in the documentary, which is narrated by "This Is Us" and "Black Panther" star Sterling K. Brown.

There are so many intriguing nuggets of information to choose from here. We can start with how the series recalls the cruel hardships of Lincoln's childhood. Lesser historians like to romanticize America's pioneer days, but as a young Lincoln's family moves from the hinterlands of Kentucky to those of Indiana, he isn't exactly experiencing the bucolic idyll concocted by countless dreadfully trite early Disney movies. Lincoln lives in abject poverty and must work to survive from a very young age; his beloved mother dies when he is only nine; his emotionally distant father temporarily abandons him with his older sister (who also later dies) so that he can find a wife in a nearby town; and, when Lincoln teaches himself to read and becomes fascinated with knowledge, his father physically abuses him because he wants his son to be a farmer.

That last detail was the one that struck me the most, perhaps because it is undervalued when people think about the Great Emancipator. Lincoln was an autodidact and his thirst for knowledge, and obvious joy in being able to learn more about the world around him, is evident both in this documentary and to anyone who has read his early speeches and poems. He took considerable pains, figuratively and literally, to find books, newspapers and virtually anything else he could get his hands on to improve his education. His mind was skeptical and had a knack for separating truth from baloney; it also had an artistic and intellectual flair, loving eloquent prose and probing ideas. This trait may even explain why Lincoln thrust himself into politics at an early age, clearly savoring the give-and-take of the Second Party System that saw Lincoln align himself with the Whig Party (the more "liberal" party by modern standards, although the term must be applied somewhat anachronistically here) with the Democratic Party, which at that time was dominated by Andrew Jackson.

These qualities sharpened Lincoln's mind and made him into the legendary wit whose comedy chops were so deft that Coco seems genuinely in awe of them nearly two centuries later. It brings to mind the famous line from "Game of Thrones" character Tyrion Lannister, "A mind needs books like a sword needs a whetstone, if it is to keep its edge." Hearing O'Brien regale audiences with some of Lincoln's most legendary sharp comedy moments (I dare not spoil them here) is a great joy of this documentary, especially since Lincoln's endearing ability to poke fun at himself is reminiscent of O'Brien's own sense of humor. (I'll just say it: My hunch is that Lincoln would have been on Team Coco.)

Yet the documentary is also strong because, when necessary, it takes Lincoln off of his pedestal. While simplistic historians tend to view Lincoln as a god-like man who with a sweep of his hand freed enslaved people, the reality is far more complicated. To its credit, the miniseries goes into detail about the horrors of slavery: The families ripped apart, the physical and psychological anguishes inflicted on its victims, the fact that America's economy depended on the degradation and subjugation of millions of people. There were men and women in Lincoln's time who wanted to abolish slavery altogether and accept African Americans as equals — but Lincoln was not one of them. He opposed slavery on principle, to be sure, but was willing to accept its existence in states where it already existed as long as it didn't expand beyond them. He believed African Americans should eventually be freed, but as the documentary astutely observes, thought they should be sent back to Africa, even though for most of them America was the only home they had ever known.

Lincoln was, undeniably, a racist. He made it clear, during a key moment in his famous debates with Democratic Sen. Stephen Douglas of Illinois, that he did not view African Americans as equal to whites. He was not an abolitionist and was only a friend to racially marginalized groups up to a point. He took political risks in his early years when advocating against slavery, but there were others who took even greater ones. And while Lincoln suffered intense hardships as a child, the documentary makes it clear, they were nothing compared to the living hell endured by American slaves.

Only the first three of the six episodes were given to Salon for review, and therefore is left off at the Battle of Fort Sumter in 1861 and the start of the Civil War. I have no idea whether the series will do justice to Lincoln's visionary leadership during the Civil War, or the events that gave birth to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment, or how he passed economically progressive measures like the Homestead Act, the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act and the Pacific Railways Acts. It touches on Lincoln's lifelong struggle with depression and other mental health issues; these were defining aspects of the man's life, and if the miniseries continues to mine that ore, it will do a great public service both for our understanding of Lincoln and on the complexity of the human mind.

The same can be said of how it discusses the great abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass, who is briefly introduced in these early episodes. Hopefully the later episodes will go into great detail about Douglass, especially since his 1876 speech on Lincoln perfectly summed up Lincoln's chief legacy — namely, that although Lincoln deserves credit for his courage and morality in ultimately acting to free enslaved people, "in his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man" and that "he was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country."

These are not criticisms of the miniseries, rather a comment on threads that I hope will be more fully explored and receive their due. I can simply say right now that the foundations have been laid, which seems promising.

There is one shortcoming in the documentary that could not have been helped, given that this was filmed before Election Day 2020, but it is regrettable nonetheless. One of the main reasons Lincoln could not prevent the Civil War was that his presidential predecessor, James Buchanan, was virulently pro-slavery and openly sympathized with the South's desire to secede. The parallels between Buchanan/Lincoln during the 1860 election and Donald Trump/Joe Biden during the 2020 election are hard to miss. On both occasions, the side of the country that lost an election refused to accept that the side that won should be allowed to govern, using far right-wing arguments and claiming that the winning side posed an existential threat to them or was somehow illegitimate despite irrefutable facts to the contrary. On both occasions, the outgoing administration (Buchanan, Trump) refused to work with the incoming one (Lincoln, Biden) even though there were terrible crises (a Civil War, a pandemic and depression) that required immediate attention. There are even similarities in the little details, such as how Buchanan and Trump were both corrupt (then again, Buchanan was not a candidate in the 1860 election and never tried to physically stop Lincoln from taking office). While the filmmakers could not have known to a certainty that Trump would act like Buchanan after Biden's victory, it still weakens the miniseries that so little attention is paid to Buchanan's reaction to Lincoln's victory. It would be like making a documentary about Biden's presidency but only giving cursory attention to how Trump created the conditions that Biden would have to confront.

Yet this is a minor quibble in the grand scheme of things. Lincoln is one of those historical figures who keeps on giving, a man whose protean gifts and complex personality makes it possible even for historians like myself to constantly learn new things. Whether the miniseries is describing in detail how Zachary Taylor betrayed Lincoln after the latter campaigned for him in Illinois during the 1848 presidential election or exploring the attempt to assassinate Lincoln in 1861 (The Washington Post recently profiled a woman who helped protect him), it is full of fun little gems — and sober reminders of the ugliness that coils beneath the surface of America's past — that will make any serious Lincoln scholar take a few moments to stop and think.

That, I suspect, is what Lincoln would have wanted.

New episodes of "Lincoln: Divided We Stand" air Sundays at 10 p.m. on CNN.

Shares