Democrats are unified behind a push for a new round of COVID relief spending even as Republicans coalesce in complete opposition.

The polling has consistently shown that a large majority of Americans, including many Republican voters, support the $1.9 trillion package that President Joe Biden has pushed for. Democrats feel they have the wind at their backs, as the budget reconciliation process will allow them to pass the bill on a party-line vote, and they recently won two Senate seats in Georgia by running explicitly on more relief funding.

So why aren't the Republicans more afraid of a backlash if they oppose it?

That's the big mystery hanging over Capitol Hill.

As the New York Times reported, Republicans are trying to message against the bill, calling it the "Payoff to Progressives Act." They're nitpicking at certain parts of the bill that they think they can make unpopular. Republican Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah wrote an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal skewering the proposed $350 billion for local and state governments, arguing that they don't need this level of funding and that it will be spent wastefully.

House Republican Whip Steve Scalise attacked the minimum wage part of the bill, Politico reported:

"As more people find out what's in this bill — and what's not in this bill — they get more furious," said Scalise, referring to things like a $15 hourly minimum wage, billions of dollars for pension funds and money for public transit and art. "Sunshine is the best disinfectant for liberal policies."

Others agreed:

"What's in it is not going to be popular," said Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.). "It's bad politics for them. Because the narrative is that they're liberal, they just spend money like there's no tomorrow, that every time there's a crisis they load it up with spending."

On this front, the parties just seem to completely disagree about the facts. Politico described Democrats as being "agog that Republicans don't see the downside in opposing a bill that polls better than most politicians do."

Democrats have a lot of reasons to think they're right. First, as stated, the bill already polls well. Republicans might hope they can turn that around with a focused campaign, but public opinion is often not so easily malleable. And up until now, prior COVID relief spending has been bipartisan and popular. The public understands that the virus is still a major problem, so it will make sense to most people that the Biden administration is offering more support. And since the bill includes direct spending checks to most families, and it's less likely that Americans can be persuaded that it's a wholly wasteful boondoggle — after all, many of them will be getting benefits personally.

Raising the minimum wage, despite Scalise's warning, is itself quite popular. It may not even end up in the final bill, but if it does, voters will likely connect it to the legislation's broader goal of creating a better economy. And it's not clear why the public will oppose funding for pensions, art, and public transit when it's clear money is going out to support people broadly.

Republicans are also complaining that Democrats are using budget reconciliation to pass the bill, which means they only need 51 votes, not 60, to get it through the Senate. But Republicans used this process twice to push through partisan legislation in 2017, so the complaints are disingenuous. And there's little indication that voters will care about these process arguments, especially if they like the final result.

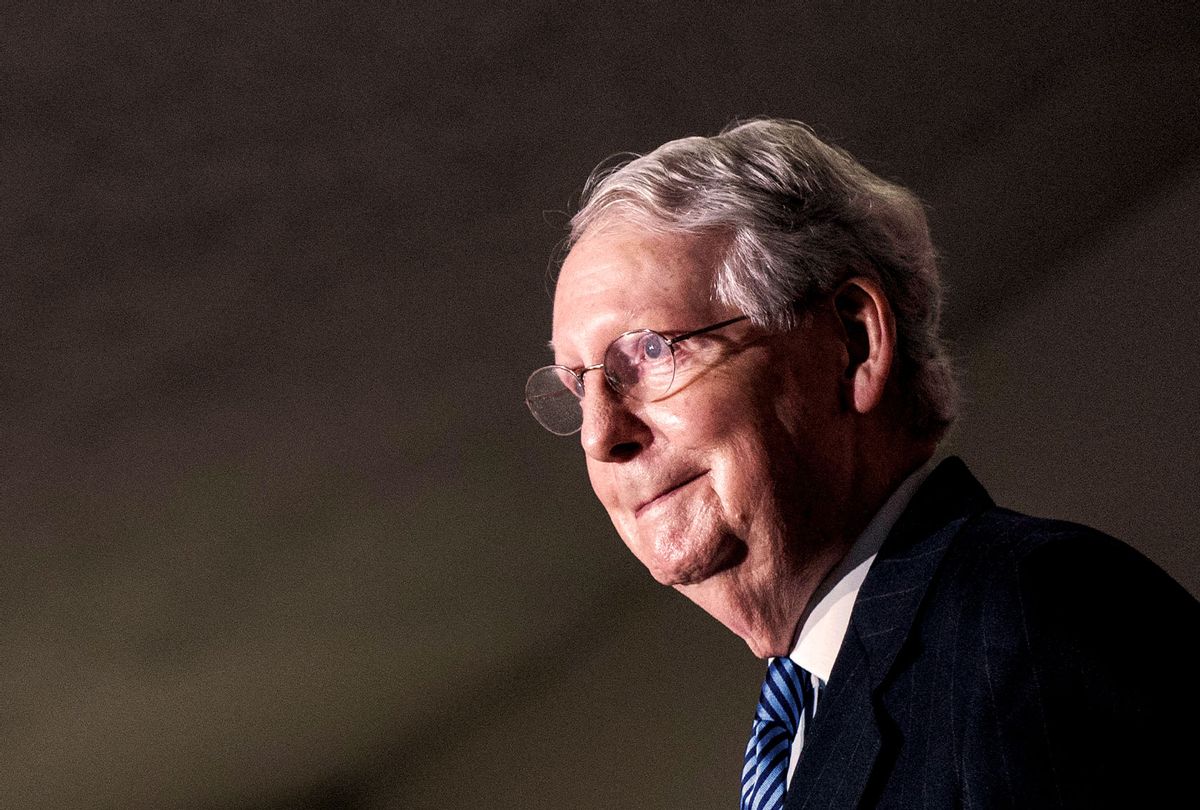

And yet, the GOP is committed to obstinance. "What you need to focus on is how unified we are today in opposition to what the Biden administration is trying to do," Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters, according to Politico.

Since their stated reasons aren't compelling in the face of public polling, is there a better explanation for the Republican Party's opposition? Should Democrats be nervous that Republicans know something they don't, and that the relief bill will backfire?

It seems unlikely. Recent history undermines that GOP's case. With hindsight, McConnell seems to have significantly miscalculated in September 2020. At that time, he has the opportunity to present the Senate with a new relief bill that would've featured more direct spending to American families and other forms of support. The checks would have gone out right before election, and they probably could have helped Trump win re-election. They might have even helped McConnell and the Republicans keep control of the Senate.

But McConnell seems to resistant to learning this lesson. He refused to bring a bill to the floor that would've sent $2,000 stimulus checks out ahead of Jan. 5 Georgia Senate runoffs, and the Democrats in the state ran winning campaigns promising to deliver those payments. McConnell now blames Trump for the loss, rather than himself.

Those episodes suggest that McConnell's own ideological leanings may prevent him from seeing the electoral implications of the policy clearly.

And it's also worth remembering that in 2017, the Republican Party focused their energies on two highly unpopular ideas: massive tax cuts for corporations, and dismantling Obamacare, which failed. They suffered mightily for these efforts in the 2018 midterms, when Democrats ran a campaign focused on health care and made massive gains in the House of Representatives, winning control of the chamber.

So perhaps Democrats shouldn't be so worried that Republicans have their fingers on the pulse of the nation and are sensing some burgeoning opposition to big spending bills. Republicans may just not be that good at delivering for a majority of voters, especially since their structural advantages mean they can often win elections even while being less popular than the Democrats generally.

McConnell and the Republicans' strategy of opposition seems to be picking up where it left off 12 years ago, at the beginning of President Barack Obama's term. In a remarkably similar set of circumstances, Obama took over and rushed to pass a large spending bill to help save the economy from freefall.

In that case, no House Republicans voted for the plan. Only three Senate Republicans joined on. By the 2010 midterms, Republicans had delivered their own walloping victory over the Democrats. And indeed, most presidents suffer big losses for their parties during the midterms after their election. So McConnell may feel confident there's little downside to the Republican Party opposing Biden's popular policy. He also may think Biden would get more of a benefit from passing bipartisan bills than if it just passed with Democratic votes.

Perhaps this is true. But refusing to give Biden any Republican support may also clarify the stakes of elections from voters, and could give the Democrats a powerful issue to campaign on in 2022.

Biden may also face more favorable conditions in the next two years than Obama did in 2009 and 2010. First, the economy does not appear to be in as dire straits as many feared. Coronavirus infections are plummeting sharply and the vaccine rollout is making significant progress. Some optimistic projections suggest we could be heading for real suppression of the virus by April; even in the less optimistic scenarios, much of the country should be vaccinated by the end of the summer. If the virus really is brought under control, the economy could snap back to life pretty rapidly, especially with the boost from the coming relief bill. It appears unlikely to suffer the same fate as Obama's stimulus bill, which many economists predicted at the time was too small for the task. Biden's relief bill also delivers support more directly to families, making it more likely to be spent and more likely to be recognized by voters as a result of government policy.

Democrats also paid a price in 2010 for another major policy item on their agenda: Obamacare. The Affordable Care Act, as it is also known, sparked confusion, fear and backlash, which the Republicans weaponized electorally, along with the sluggish economy. The benefits of Obamacare took far too long to make an impact in people's lives for the Democrats to benefit from it electorally in the midterms.

Biden's second priority after the COVID bill, on the other hand, has the potential to be much less contentious. He wants to spend trillions more on infrastructure across the country — another hugely popular idea. While there may be downsides to his plan, and Republicans will try to rally against it, infrastructure lacks the fraught tradeoffs that are implicated in any major health care overhaul. Biden may be able to avoid the second-year backlash Obama wrestled with.

Even despite all that, Biden might lose his Congressional majorities in the 2022 midterms. Presidents usually do. But with some fortunate outcomes with the virus and the economy, and the right mixture of popular policies that voters can quickly benefit from, Biden might find the key to defying history. And McConnell might come to regret his big bet on opposition.

Shares