Who knew that in 2021 spoken word poetry would be embraced by millions for its significance as a nation-building anthem from the lectern at Joseph Biden's 46th presidential inauguration? In her poem "The Hill We Climb," astounding Amanda Gorman's cry to "rebuild, reconcile, and recover" with "every breath from my bronze-pounded chest" sounded in striking resonance with the man in whose name she addressed her nation, whose speech has also been the occasion for celebrations of recovery. Biden's well-publicized efforts to speak with and overcome a stutter have operated as an extended metaphor for the restoration of democracy that has now become his task in the aftermath of the political abuses under Donald Trump.

Even Gorman's evocative hand gestures silently pointed towards the body movements (blinking and head-nodding) that many have noticed are associated with Biden's speech, what Eric S. Jackson explains are "accessory or compensatory behaviour . . . that sometimes helps or sometimes seems to jolt us out of a moment of stuttering." Gorman's own experience with a speech impediment, a common pronunciation difficulty known as rhotacism, only further echoes this emergent theme. Gorman's efforts to overcome her impediment by reciting "Aaron Burr, sir," from Lin-Manuel Miranda's hit play "Hamilton" and Biden's attempts to overcome his by reciting lines of poetry by William Butler Yeats jointly brought poetry into surprising focus as the vehicle of the democratic project of overcoming.

Even the use of metaphor as the glue binding speech impediments to the work of democracy brings language and speech to the forefront of US federal politics as the political occupation of the nation. The Atlantic's John Hendrickson points out that Biden's frequent references to how he "overcame his speech problem" are an uplifting refrain for the national project he has been given on the heels of the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol that threatened the nation's democracy at its core. Democracy, with its emphasis on freedom of speech and expression, could hardly have been spoken up for better than with the example of two restored speakers overcoming vocal impediments to freely address an impeded country.

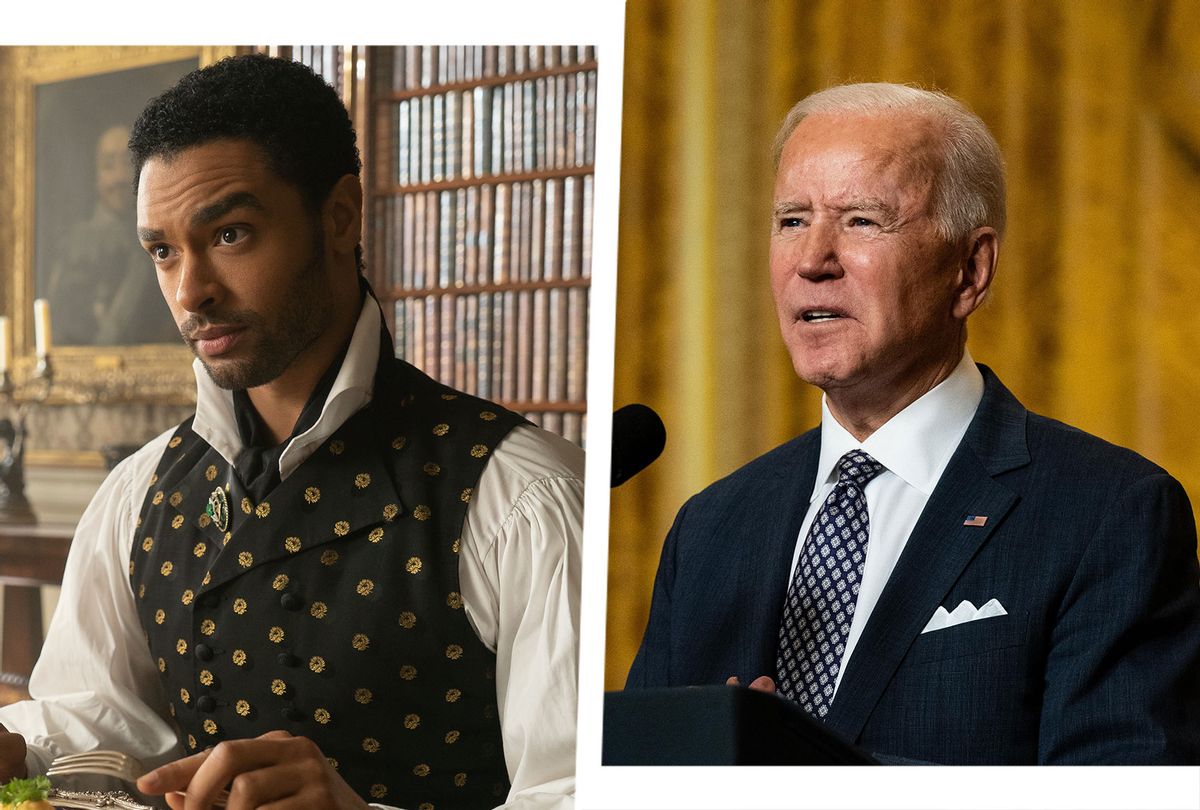

So perhaps truth would be exactly as strange as fiction when another salute to 19th-century speech quickly became the most popular Netflix series of all time. "Bridgerton," Chris Van Dusen's hit Regency romance from the media empire of Shonda Rhimes, is narrated by the the pseudonymous Lady Whistledown (Julie Andrews), the sassy gossip columnist whose cheeky observations are regarded as a threat to the order of the aristocratic, multi-racial town in what some call a revolution in women-centred television and what others dismiss as a bad Austen knock-off. Besides its comparatively convention-laden and puerile storytelling, the relation to Jane Austen's domestic fiction is drawn by the show itself with its first narrated lines, an altered rendition of the opening sentence of "Pride and Prejudice."

But beyond the swooning and bodice-ripping, the show's intertextual theme of the force of galvanizing speech finds its mark in the childhood stutter of the rakish Simon Bassett, the Duke of Hastings (Regé-Jean Page). The story of his struggle to speak under the neglect and verbal abuse of his domineering father, and his overcoming the impediment with the help of a supportive aunt to produce the fluent, confident voice that so dizzies the young Daphne Bridgerton (Phoebe Dynevor), reproduces well-worn psychopathological theories about the causes of stuttering.

In Simon we see the familiar narrative of the preternaturally shy, sexually inhibited stutterer, made as such in the crucible of bad parenting and who through gritty self-confidence and proper love becomes the sexually mature virtuoso. Only Simon has taken these prescriptions too far, for his oedipal inhibitions have transformed into the oversexed detachment of a slippery rake who refuses to father a child. Only with Daphne's restorative, heterosexual love can he overcome his overcorrection and become a fully functioning reproductive adult and produce an heir of Hastings for the fluency of his dukedom.

The correspondence between speech impediment, sexual suspension, and nation-building is a trope we saw in the popular 2010 film "The King's Speech," where a young King George VI (Colin Firth), aka Bertie, works with the speech therapist Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush) to treat his stutter. During a therapy session the two men speak of the prince's childhood while he regression-plays with a model airplane belonging to Lionel's young patient. Lionel asks him if he and his brother David "chase[d] the same girls." "David was always very helpful in arranging the introductions," he admits. Bertie has come to Lionel on this day shortly after his father's death and ostensibly because of "my brother" (who will briefly serve as the King of England). In this oedipal moment, as his father passes and his brother ascends, the future king confesses his pain – from the nanny who withheld love to the brother everyone adored. With Lionel's help and the aid of early prosthetic technologies for producing what is now known as delayed auditory feedback, Bertie will overcome much of the evidence of his impediment in his public speeches to do the work of nation-building and unite the United Kingdom in its renewed postwar era around the sign of its increasingly fragile monarchical democracy.

For "Bridgerton"'s Simon as well, the continuity of a racially united feudal stronghold is embodied by the Duke's oedipally suspended heart. He is one of several Black aristocrats who make "Bridgerton"'s reimagining of the genre so unique. As his aunt the Lady Danbury (Adjoa Andoh) explains, their own family's inclusion in the aristocracy and indeed the royalty became a reality with a similar dose of restorative love. "We were two separate societies divided by color until a king fell in love with one of us," she says. "Love, your grace, conquers all." Lady Danbury's promise to the young Simon to "help you overcome this stammer of yours" is the first expression of this "love" that conquers even racism, nations, and stammers.

Similarly, 2020 saw a transformation of the Black Lives Matter movement, when in response to George Floyd's last words, "I can't breathe" – themselves an echo of Eric Garner's last words under the knee of anti-Black police violence – Black voices were heard worldwide in a sea change of protest in support of the basic right to life and liberty: to breathe and with it, speech. We heard the vibrations of these horrendous thefts of breath in Gorman's own "breath from my bronze-pounded chest." Simon's symbolic triumph over the speech-impeding abuses of his Trumpian father pre-echo Gorman's testament that "love becomes our legacy" when through the constancy and adoration of Daphne he is able to over-come inside of her and create a son to carry on his own legacy.

This intersection of speech therapy, nation-building, and Blackness has a long history in both the United Kingdom and the United States where correcting children's speech has been part of a larger project of racial and class assimilation. In the 20th century, reciting poetry and the formation of "speaking choirs" were employed to erode traditionally Black speech patterns as well as those associated with regional and lower-class dialects. Verse or speaking choirs were widely embraced as a progressive reform designed to "assist the disadvantaged in overcoming the perceived liabilities of their backgrounds," as Joan Shelley Rubin explains in "A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the United States."

Patterns of speech associated with the "best-educated" class of a region were introduced via choral speaking (a form of auditory feedback related to Lionel's early prosthetics) to reverse the influence of race and class on speech. In the same text, British-educated Wellesley College speech faculty member Cecile de Banke decries nasality in American speech as a "nation-wide handicap . . . a mark of boorishness [and] lack of culture." In this tradition, poetry recitation has its use in bringing about a new sound of Americanization that "yoked all the poetry [being read] . . . to a genteel definition of culture as refinement."

As we breathe new breath into democracy through poetry, representation, and marginalized voices, let us embrace renewed metaphors as well, ones divested of the damaging and ableist expectation to speak well by overcoming the intricacies of our individual voices. Hear the United States' stutterer-in-chief lead a new defense of truly democratic principles through stops and starts, pauses and blinks and head nods, as a new language for a new freedom. Poetry, with its line breaks, enjambment, repetitions, and attention to language sounds is itself a kind of impediment to language that opens language up. Let us hear the brokenness of poetry, its rejection of conventional and acceptable language, to express political possibilities that can be lived and breathed not in the overcoming of difficulty but in the stops and starts of a precarious future.

Shares