Powerful men of the world are facing a reckoning. The list of influential men facing public allegations of sexual harassment and assault grows weekly, as it has for years. And while all of those men have their differences, they are linked by one major life event: all were once boys. Yes, it feels hard to say aloud, yet it’s true — all so-called bad adult men began life as innocent, and in many cases, sweet boys.

Parents are apt to heed this knowledge. What went wrong in the childhood of, say, Harvey Weinstein? And how do we stop sweet and innocent boys from growing into men who do horrible things?

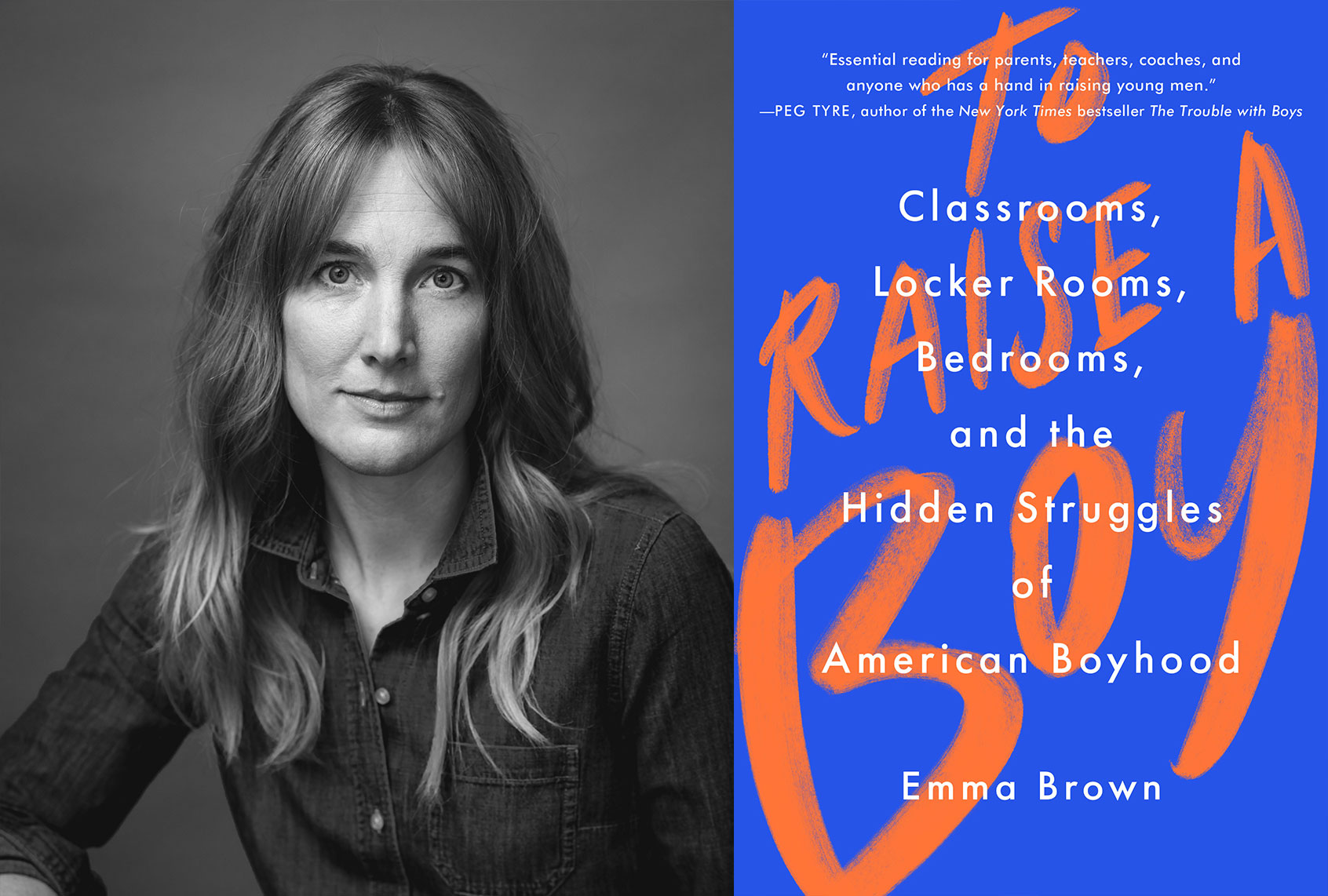

It’s a question journalist Emma Brown seeks to answer in her new book, “TO RAISE A BOY: Classrooms, Locker Rooms, Bedrooms, and the Hidden Struggles of American Boyhood,” which comes out today. In 2006, activist Tarana Burke coined the phrase “#MeToo” to foster empowerment among women of color who had been sexually abused. Over a decade later, the phrase evolved into a viral hashtag, popularized by actress Alyssa Milano in the wake of an explosive investigation into claims of sexual misconduct against Harvey Weinstein.

While the Weinstein allegations unfolded, Brown was nursing her six-week old son watching the reckoning unfold on her phone. “The wave of all that, the weight of it, left me breathless and sometimes furious,” Brown writes in her book. “And it left me, too, with a persistent, niggling question: How would I raise my son to be different?” Six months after giving birth to her son, back at work she received a tip from Christine Blasey Ford and broke the story about Brett Kavanaugh.

Raising a son while reporting on #MeToo took Brown on a year-long investigative diversion, in which she interviewed researchers, parents, boys, coaches and educators. Her goal was to learn how she could raise her son, and all sons, to have better relationships with women, other men, and themselves. “I’m embarrassed to admit that I had never given much thought to how boys learn to be boys until that moment in time in late 2017, sitting at home with my chubby, cooing infant son, reading about the wrongdoings of men,” she writes. “These men had been infants once, too. And then they had grown up.”

What she discovers is that men, like women, suffer dangerous gender stereotypes as boys that harm their mental, emotional and physical health. In her book, she discusses how the rise of porn coincided with the decline of effective sex education in American public schools — which, taken together, makes it challenging for boys to understand boundaries and consent. She examines the importance of male friendship and mentors, and the effectiveness of burgeoning outreach and support programs. Brown leaves readers with a feeling of hope, but doesn’t downplay the challenges boys face today.

“While girls have long been allowed and even encouraged to be boyish, we are finally starting to rethink the penalty we’ve made boys pay for being girlish,” Brown writes. “More parents and teachers and coaches are starting to realize that we owe our sons the same message we are trying to give our daughters: you can become whoever you want and pursue whatever you dream.”

Salon interviewed Brown about her book; as always, the interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I love the backstory, and obviously it’s a very personal subject to you. I thought it was really interesting how you start off right away saying that people should lay off the term “toxic masculinity?” Why did you set the stage with that opinion?

As I was talking with boys and young men, I learned from them that that term, for many of them — not for everybody of course — but for many of them, was a really difficult term to take. And I think that when folks I was talking to, when they heard that word many of them felt like they knew where whoever was saying that, they knew where that person was coming from. And it wasn’t coming from a place of empathy for what it’s like to be a boy or what it’s like to be a young man. And so, in my conversations with boys and young men, I just don’t find it to be helpful because it’s so freighted and loaded with all of these conversations that sometimes you don’t even know it’s carrying for the person that you’re talking to.

So that’s why I choose not to use it. I think I quoted a boy in the book who I talked to, a high school student. He said, if you use that term nobody’s going to listen to a word you say. And so if we want boys to hear us, and we want to support boys, I think it helps to use language that they can hear and embrace.

In one part of the book you asked how we can tell boys that they must be empathetic on the one hand, yet fail to show them empathy on the other hand. I’m curious, after reporting your book, do you have an answer to that?

Well, I think we all thrive with support, right? We all need support. And that can look a lot differently in many different ways. But I think empathy is a good place to start with everybody, and if we want, just as I wrote, if we want boys to be empathetic to others, we need to be empathetic to them.

I was just pretty astonished to realize how much stress and pressure there is as a boy. I grew up thinking about all the ways in which I had to overcome my femaleness. I wrote in the book about being in eighth grade and the girls were told to play volleyball with a giant beach ball while the boys got to play with a real ball. And that’s just a tiny example, but there are a lot of ways that we are sort of familiar with thinking about how girls have been put in a box because of their gender. And I think we’re less familiar with thinking about the ways that boys are put in boxes because of their genders.

It was really eye-opening to me to talk to boys and young men about what that’s like for them, and how hard it can be when they try to push past the limitations of those boxes and expand the definition of what it means to be a boy. So, yeah, I have great empathy for boys and the particular pressures that they face growing up in America.

Want more science, health and parenting stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

You refer to the “man box” that men are forced into in America — this idea that they have to be stereotypically masculine. And you talk about the role that fathers play in building it up and tearing it down. I definitely walked away from the book more thinking the solution is in the school system, and our public rhetoric. But I’m curious if you can share more like how you think fathers can build it up and tear it down.

I think that relationships in our lives are just hugely powerful forces. And that goes for, particularly, of course, for our relationships with our parents. What was interesting to me was to read research, and then speak with fathers. I found that for fathers, the way your son is can feel like a reflection of your own masculinity. And that can be tough for dads. But the flip side of that is that dads have so much power to sort of help boys think about what masculinity is.

So there’s research, for example, that boys, young men who are in college, who can recall their dads caring for them, doing things like taking them to the doctor, or caring for them when they’re young, are more likely to envision having a more active role in their own kids’ lives.

I definitely think we’re seeing a shift like that in younger parents. I thought that the first chapter on sexual assault against boys was really eye-opening. I didn’t know about “brooming,” or know how common it is for men to be sexually assaulted at school. From your perspective as a former teacher, what do you think needs to be done to take these reports and these acts of sexual violence more seriously in schools?

I think learning about the experiences of boys who have been sexually assaulted, particularly by their peers, was incredibly hard and eye-opening for me. I saw how shame is just a really corrosive force. Boys who are sexually assaulted — and as you say, it happens more often than we talk about or more often than we really recognize — it’s just incredibly hard for them sometimes to even understand that what happened to them was sexual assault. Much less admitted to themselves or admit it to somebody else. So I guess, you know, and I’m going to talk specifically here for a minute about boys as victims of sexual assaults, I think we really owe it to our sons to give them the same message that we are trying so hard to give our daughters, which is that your body is sacred and it’s yours. And that you get to decide who touches it.

For a long time, many schools have not been very good at dealing with sexual harassment and assault, and it’s gone unpunished and unrecognized, which makes it seem in some schools where it’s a real problem like it’s normal.

On the other hand, we don’t want to be cracking down and just suspending kids or expelling kids for the mistakes that they’re making in the course of trying to figure out life. And so I think one thing schools and parents and communities need to do is figure out how to hold young people accountable in productive ways, so that they can learn from their mistakes and grow. And also so they can keep victims of really horrific behavior — like what you’re talking about, the brooming — safe. So, we aren’t doing that very well right now in schools. I don’t know that we’re really doing it very well as a culture either.

Do you think that suspensions are an effective form of discipline in schools?

I think that boys need support to learn from their mistakes and grow. It’s hard to make blanket statements about any form of discipline, but I think what we see is that if children are simply sent home without the support to learn how to take responsibility for the mistakes that they’ve made, try to make amends with the person that they’ve hurt, or sort of repair that harm in some way, then I’m not sure they’re getting the support that they need to really learn and grow from their mistakes.

In fact, there’s piles of research that shows that suspensions are associated with really poor outcomes, in terms of higher likelihood of dropping out and other things like that. So I think we need to think more creatively about how we support boys so that they can learn from mistakes that they make.

I write about restorative justice as one model for that. And restorative justice is the process of sitting with the person that you have harmed, accepting responsibility for the harm that you caused, and coming to some agreement about how you can repair it. It’s really controversial to use [restorative justice] for sexual harm because of the power dynamic that can happen when you have a victim and somebody who hurt the victim sitting in the same room, but it is being done more and more. And it’s being done with some kinds of sexual assault here in Washington, D.C. with great success, according to the prosecutors who are sort of overseeing that program.

I thought that part on restorative justice was really interesting. I understand how it can be controversial, especially in cases of sexual assault. You mentioned that there is some success to it. Why do you think restorative justice is not being widely implemented in America’s public school system across the country?

Yeah, I think restorative justice has become much more common in public schools over time. I’m an investigative reporter at the [Washington] Post now, but I used to cover local and then national education. And over the course of my time covering education, it certainly became much more common. But I think, as with all things, restorative justice, the ideal of how it is practiced can be different than how it is practiced on the ground, under the constraints of time and money and resources. So the question is, do schools have the time and money and resources to do restorative justice? Not only to do restorative justice, but to do it well. And I think that varies widely depending on the school you’re in.

After MeToo, as a society, we’ve had to ask really big questions: What do we do with men who sexually abuse, assault and harass others? Your book explores how to raise men to be themselves, not what our culture tells them to be. But I’m wondering if through your reporting, if you found any answers to society can better handle adult men?

Yeah, as you said, I didn’t really focus on that question in this book. And I did focus more on what can we do differently so that that doesn’t happen. And I guess I want to highlight this idea of shame as a really powerful force that we should think about when we’re thinking about what can drive behavior that hurts other people. And when I say shame, I mean boys feel such pressure to be manly enough among their friends, among other boys, and fear that they won’t be seen as manly enough — and that that can, for example, drive sexual harassment. Boys are thinking more about impressing their friends than they are about the girl or young woman who is on the other end of their harassment. And that is something borne out in all kinds of research. So that’s one reason why it can be really, I think, a powerful tool to help boys think beyond really narrow ideas of what it means to be “manly.”

While I was reading the book, I was just wondering why even very young boys try to impress each other with how “manly” they are. I mean, do you think it’s because of the media they’re consuming? I know you talk about porn and childhood and access to that nowadays. What do you think?

I think that there’s no one answer to that question. We are all sort of swimming in stereotypes about what it means to be a boy, and what it means to be a girl. And we as parents reinforce some of those without even realizing it.

Sex education has been evaporating out of a lot of schools over the last few decades, which was surprising to me, even though I covered schools for years. And at the same time, online pornography has become pretty ubiquitous. And that leaves our boys in this situation of learning about intimacy from online pornography, which is dangerous for them and it’s dangerous for girls too.

I spoke to a young woman from Maine who described to me a boyfriend who would choke her in the middle of sex without asking her first, because he thought that that was sexy. He had been watching pornography where choking is not unusual and had that misconception. So when we leave boys to learn without the support and guidance of sex education and honest conversations, then we’re putting them and their partners in that situation.

Emma Brown’s book, “TO RAISE A BOY: Classrooms, Locker Rooms, Bedrooms, and the Hidden Struggles of American Boyhood,” comes out March 2, 2021 from Atria/One Signal Publishers.