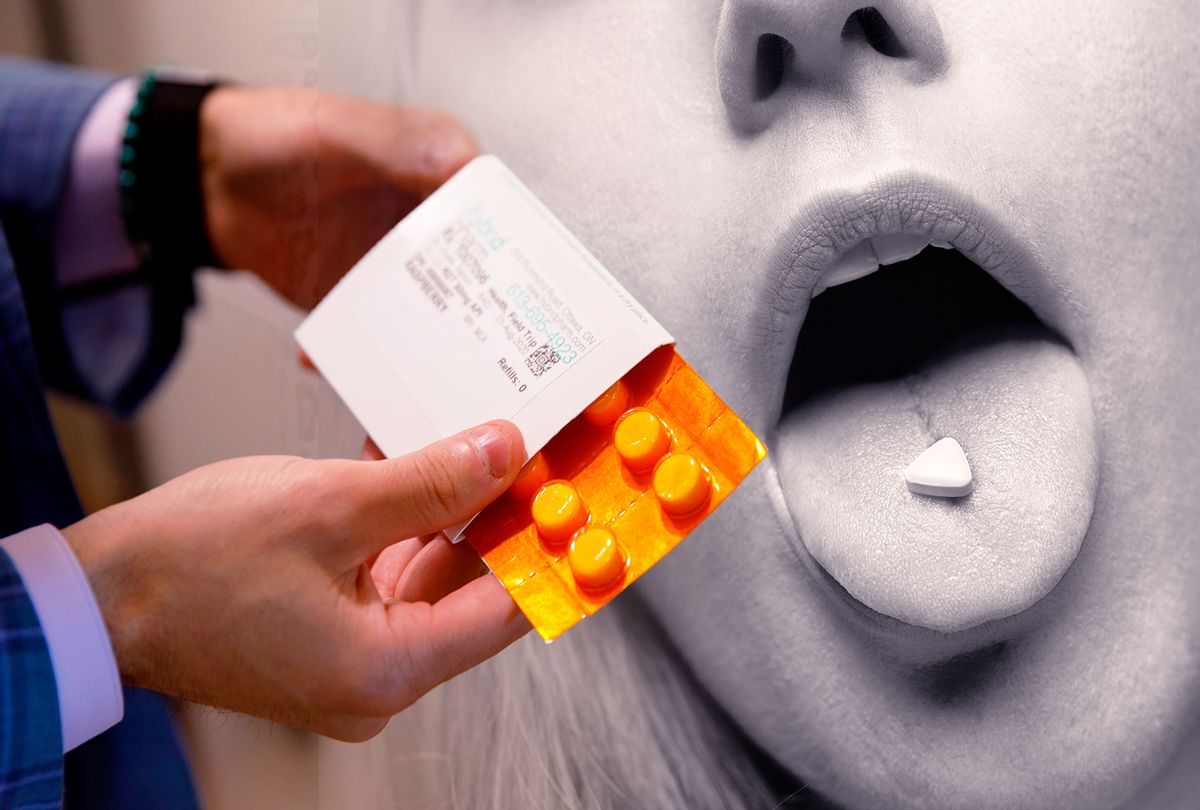

Supposedly, we are living through a "psychedelic renaissance." From ketamine antidepressants to MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, the medical use of psychedelic drugs is portrayed in the media as a boon for the mental health profession, which reports seemingly miraculous results for treating some of the most significant mental health issues facing our time. The FDA has granted "breakthrough" status for both psilocybin and MDMA as treatments, and venture capitalists are placing bets on psychedelics to curb the trillion dollar public health burden.

As psychedelic advocates and practitioners with decades of experience, having worked with thousands of people, we believe we need a serious examination of whether the current mental health industry is the place for psychedelic drugs. Looking at the industry historically, there have been repeated claims of breakthrough modalities that would bring psychiatry into the realm of medical science. Yet none of these claims have demonstrated a high benchmark of legitimate authority, and many have even been harmful. While we applaud the efforts that are underway for decriminalization, and are excited by the potential to learn from the wealth of traditional and underground practitioners, much will be lost in the process of medicalization.

The model for introducing psychedelics into a medical framework is being defined by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), the most visible and politically connected psychedelic organization. Their flagship research project is using MDMA, a psychostimulant, to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a diagnosis that has become increasingly common. Its public association with war vets and sexual abuse survivors makes PTSD the perfect public relations focus for psychedelics as the next medical breakthrough.

Ross Ellenhorn, Ph.D., the author of "How We Change "and an owner of a therapeutic program, has been an outspoken critic of overmedicalization in the mental health field. Ellenhorn says that the terms "'breakthrough,' and miracle cure,'" form "part of a larger discursive power in medicine, in which people volunteer to be the subjects of power."

"First, they label certain experiences as things that need to be fixed by a cure: that there is a disease, and a skull-bound one at that," Ellenhorn explains. "Second, that means that the people who won't subject themselves to the cure are doing something wrong and irresponsible. In more clinical terms, they are in denial. They are deviating from their role as sick people: the responsibility in that role always being that you get help."

"It's really concerning right now that psychedelics are being sold as 'miracles,' and even that exact word is being used," he continued.

The promise of a cure has a real effect on people who are looking for help. This was the case for "Mel," a participant in one of the MAPS' Phase III clinical trials with MDMA, who described their initial enthusiasm about participating. (Mel is a pseudonym; their name and gender-identity have been changed in order to protect their identity.)

"Everything that I read, everything that I heard about, was how this stuff will fix you," Mel told us. "This stuff is going to make you better. It's going to make you unbroken. It's going to put all the pieces back together."

A survivor of serial sexual abuse as a child, Mel, now in their 40s, had been on psychiatric medications from the age of 10 and later turned to alcohol and drugs. After decades in recovery and a long history of working with psychiatrists and psychologists, nothing had worked. Following the loss of their mother, they said they finally "snapped" and felt like they were at the end of their rope.

After their first MAPS-administered session with MDMA, Mel felt ripped open. "Every defense mechanism that you have gets stripped from you," Mel told us. "The thing that kept me getting up every day was that sense of disconnection, and suddenly, I couldn't disconnect anymore. There were times I thought I was going mad. I never experienced PTSD flashbacks in the true sense before, but after that first MDMA session I did. I would wake up in a totally different place in my apartment huddled in a corner. I didn't know where I was. I didn't know how old I was. I didn't know who was there and who wasn't there."

In 1980, PTSD was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the "bible" of psychiatric diagnosis, which meant that it became a certifiable diagnosis. That change has helped countless patients access care, funding, and housing, and led to greater awareness of the long-term consequences of violence. Yet the recognition of PTSD as a diagnosis has also been criticized for medicalizing symptoms that some develop as useful coping strategies against trauma. Dr. Bonnie Burstow, the late professor and feminist psychotherapist, stated in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology that even the interests of traumatized women and children are not well served by the PTSD diagnosis.

"The diagnosis itself turns the aftermath into a disorder and turns the violence itself into nothing but a preceding event," wrote Burstow. Thus, it labels coping mechanisms as "symptoms," which are then subjected to treatment in an attempt to remove them. There are those who have found relief from suffering through these diagnoses and the existing pharmacotherapies. In some cases people find important identification and even community from them. However, psychiatry's tunnel vision can often be more harmful than healing, which is particularly concerning with the rawness and vulnerability brought about by psychedelics.

Since the early 2000s, the best funded and most visible psychedelic research has focused on PTSD and other disorders classified in the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). As a collated list of categories and symptoms, the DSM defines professional and popular understanding of mental illness.

In recent years the DSM has been denounced as "scientifically meaningless" by mainstream psychiatrists, and its relevance has been questioned by its own authors. The chair of the DSM-IV task force, Allen Frances, was so appalled by the current version, the DSM-5, that in 2013, he published a critical book, "Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life."

That same year, under the direction of Dr. Thomas Insel, the National Institutes on Mental Health (NIMH) abandoned the DSM as a research instrument. In a statement on the NIMH website, Insel wrote, "Symptom-based diagnosis, once common in other areas of medicine, has been largely replaced in the past half century as we have understood that symptoms alone rarely indicate the best choice of treatment."

Psychedelic science portrays itself as a vanguard revolutionizing mental health care, while remaining firmly focused on developing treatments defined within these same antiquated models. An early and vocal critic, Dr. Bruce Levine, a practicing clinical psychologist and author who has written extensively on the topic, says that, now, "there is nothing more mainstream than to trash the DSM." Nonetheless, the field of psychedelic research has simply ignored this widespread criticism for political and economic expediency.

"On a scale of 0 to 10, where 10 is real science and 0 is not science at all, I would put the DSM at a 0," says Dr. Levine. "These are just wastebasket categories for behaviors that create tension, behaviors from individuals who make psychiatrists uncomfortable, and who psychiatrists judge make others feel uncomfortable."

Interviewed from his home, Dr. Bruce Cohen, Associate Professor of the Sociology of Mental Health at the University of Auckland, and author of "Psychiatric Hegemony," said, "What the profession does, and what these diagnoses do, is to act as a discourse of social control. The same as police, the same as the criminal justice system — this will reflect the dominant norms and values of whatever society it's in." This is explicit and fundamental to the DSM, which defines personality disorders as "an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual's culture."

The hope has long been to discover, for the field of psychiatry, the equivalent of what the antibiotic was to the field of medicine. The theory of chemical imbalances followed, along with the widespread introduction of antidepressants. Decades later, the editor of the Psychiatric Times, Dr. Ronald Pies, wrote that no "knowledgeable, well-trained psychiatrist" believes mental disorders are caused by chemical imbalances, saying it was "always a kind of urban legend." And Dr. Joanna Moncreif, a critical psychiatrist and researcher, clarified in the British Psychiatric Journal the now widely held view that, "there is no evidence that antidepressants work by correcting a chemical imbalance... and evidence suggests they produce no noticeable benefit compared with placebo."

The search for psychiatry's antibiotic has fallen flat. Admitting that, "Current treatments are failing patients," Dr. Ben Sessa, a prominent psychedelic researcher and psychiatrist in the UK, is part of a revival of this same antibiotic narrative in a psychedelic context, saying that now MDMA could be "as important for the future of psychiatry as the discovery of antibiotics was for general medicine a hundred years ago."

Robert Whitaker, author of several books on the subject including "Mad in America," voiced concern about moving psychedelics into this arena. "Psychiatry itself is feeling a bit delegitimized right now. They told a story about chemical imbalances and drugs that treat those chemical imbalances, which is being revealed as a fraud. They need a new story to tell." The burgeoning psychedelic industry is marketing yet another new hope that the roots of suffering can be extracted "quickly and conclusively," but Whitaker says, "you have to tell a corrupt story about what psychedelics do to fit them into that model."

Even for the most well-meaning researcher, accurate measurement of changes to symptoms can be a challenge for a number of reasons, one of which is a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne effect. Specifically, people tend to change their behavior when they know they are under observation, especially when they feel that their participation is valuable. MAPS has generated massive public support and media presence for their research before it has ever been conducted, let alone published. One result is that research participants can develop a major sense of involvement in this movement, and a sense of responsibility to help shape its future.

Mel described how this influenced them. Once they learned about the MDMA studies they were determined to enroll, reaching out to every site in the country, even offering to move to another state in order to be admitted. They researched the study's protocols online, looking through the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the measurements that would be used. "I wanted to place myself right in there. Not in a dishonest way. Nothing was fabricated, just holding things back because I didn't want to be too crazy to get in."

"I wanted to be fixed," they said, "and I felt great responsibility. At the time I felt that if I didn't get better then the FDA was not going to approve it. I was going to fuck up their numbers and then it wasn't going to be legal, and millions of people were not going to have access to it." As a result, Mel said, they "only gave them the good stuff that was happening. I really omitted a good number of things that were challenging and difficult… It was more of reporting how things were getting better, because that's what I really wanted, and part of me really believed that too. That's what I wanted so badly that maybe I could convince myself."

In December, 2020, Rick Doblin, the founder and executive director of MAPS, announced with, "an enormous sense of pride, satisfaction, and relief," that their Phase III MDMA trial had produced "statistically significant" results in lowering symptoms of PTSD. However, the benchmark for statistical significance according to this very limited set of criteria is a far cry from the widely hyped ideas that underpinned Mel's hopes. Statistical significance in altering self-reported changes to symptoms does not mean that MDMA or psychedelics address the underlying issues so completely that coping mechanisms become unnecessary.

These unrealistic expectations are part of what Tehseen Noorani, Ph.D, an anthropologist who worked as a psychedelic researcher at Johns Hopkins, calls the "Pollan effect." The name refers to the author Michael Pollan, and the dramatically heightened expectations people have of psychedelics healing effects after reading stories like the ones found in his bestselling book "How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence." Noorani told us that "clinical researchers are finding these expectations difficult to grapple with, but they are likely influencing the results."

In Noorani's article, in which he coined the term, Dr. Albert Garcia-Romeu, a Johns Hopkins researcher, admitted, when asked, "It's a huge problem… you want people coming into this with some openness, and typically once you have all these preconceived ideas, they think they know what they want. That doesn't always work out well."

Mel said that the therapists and other researchers were talented, kind and caring. Those involved in the Phase III studies are some of the most competent and experienced professionals in the field. Mel said they did have meaningful experiences during the trial. However, the container that was required by the research, which is designed to fit these drugs into the healthcare system, simply wasn't suitable to process the experience. At the end of the three sessions, Mel felt they had not had the white light transformation they had expected from all the media coverage. "I was still horribly broken and it was devastating," they said. "It shattered me in a whole new way." Now Mel meets regularly with an informal support group for others who had negative experiences during or after the MAPS trial.

One of the long-term positive changes Mel did mention was connecting with underground psychedelic practitioners and continuing to work with those medicines without the restrictions of time and procedure. With decades of experience and a more personal approach, these people helped them to reframe their narrative about their trauma and the path of recovery, outside of the narrow confines of the DSM. The reality is that millions of people have done psychedelics for spiritual, therapeutic or recreational purposes and have had healing experiences. Their anecdotal stories are what have inspired the current research, but only a tiny minority have done so under the care of a psychiatrist or conventional therapist.

If psychedelics hold promise, maybe it is because they do not work in linear ways or provide overnight results. Psychedelic experiences can be expansive. They can lead people on paths of self-inquiry and growth that extend through time and space, bringing forward new challenges and insights that become personal reference points, even years later. As Robert Whitaker points out, "That doesn't fit a medical model that gets you FDA approval. You can't say we have these agents for exploring and coming to think differently about the world." The necessity of reductive research here is to come up with a strict clinical protocol that will lead to replicable changes for anyone with a given diagnosis. This rigidity belies the organic and expansive nature of the psychedelic experience. "If they're going to be agents of exploration," asks Whitaker, "why do you need a doctor for that? Why do you go to medical school for that?"

There is a need for research into psychedelics as they present an opportunity to recontextualize how we think about and experience suffering. However, drowned in the media hype of psychedelic advocacy organizations and the mental health industry, there is little public discourse about the potential implications of moving psychedelics into a system with such a problematic history.

Recent localized efforts to decriminalize psychedelics offer some hope that the underground and traditional practitioners can continue to work with less risk of arrest. It may even provide the opportunity for them to come up from the underground, and to act as mentors and teachers to the less experienced medical and therapeutic professionals, conveying a more nuanced understanding.

As a result of the more expanded perspective that Mel found working with underground providers, they found a way to contextualize the PTSD narrative. Although they didn't believe in it before, they now say, "My partner and I often joke that I didn't have PTSD until I finished the trial."

Want more science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Shares