Estrangement and stigma go hand in hand. Even if we accept the contemporary parenting precept that every family is a dysfunctional family, the thought of being fully cut off from one's own blood is still appalling. Joshua Coleman wants to change that, and help bring estranged parents and children back together. But that takes a lot of work and painful honesty.

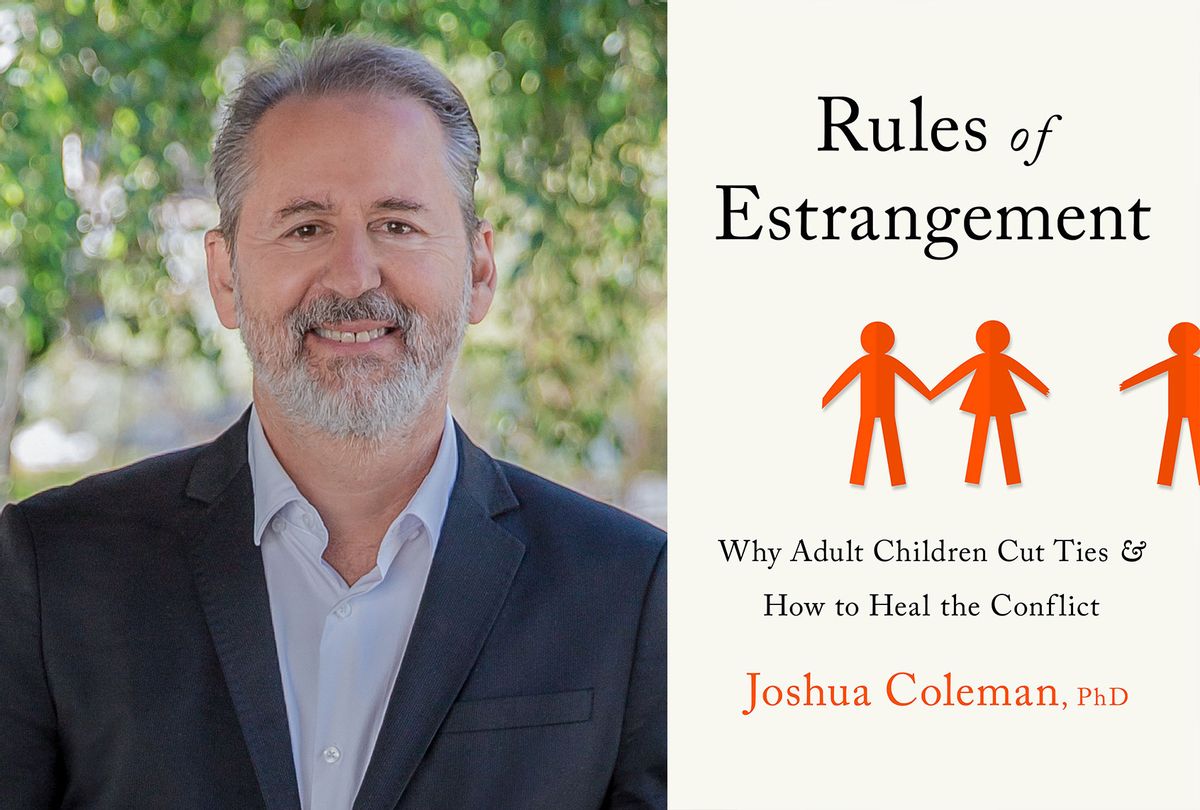

The Bay Area psychologist, who frequently works with parents trying to bridge the divides with their adult children, knows a lot about the causes of estrangement and the tools required for reunion. That's because his expertise is not merely professional: his own daughter did not speak to him for several years. The two have since reconciled, and Coleman has now put what he's learned together in his new book, "Rules of Estrangement: Why Adult Children Cut Contact and How to Heal the Conflict." And while he's clear there are no guarantees or easy solutions, he offers a path toward hope, growth and healing. Salon spoke to Coleman recently about the root causes of estrangement — and why it's on the rise.

I have a firsthand experience of estrangement, and there is so much shame around it and there is so much secrecy. But at least as the child, people often come around to, "Well, you must have a crappy mom." If it's your kids, I suspect no one says, "Oh, you must have crappy kids." If a child is estranged, I imagine that the burden on parents is so much greater and so much harder to bear.

I think that's true. And I appreciate you saying that, as the estranged adult child, because there can be this tribal, generational war of concepts around this. I think that if you [view] that from the parent's perspective, the identity of parent is such a powerful construct. It has so many different layers of meaning and self-assembly that it can get really rich and profound in terms of providing happiness and sense of belonging with other parents. When it's removed and your kid stops talking to you and that feeling of being really cut off from the identity of being a good parent, the shame that comes from that self-isolation, the feeling of failure, particularly with mothers, is incredibly profound. I work with both estranged adult children and parents, and also do family therapy and reconciliation therapy. And still, there's plenty of shame from the adult child's perspective as well. Like, "Well, what's wrong with you? Call your parents." That sort of thing.

You identify first and foremost in this book how you start with yourself as the parent and how you start with looking at your own past before you even move on to, "How am I going to have this reconciliation?" That's a hard thing for people to do.

It's really hard, absolutely.

How do you tell people to start with themselves? How do you tell them to get real about putting themselves in their child's shoes and saying, "Okay, where did this come from and what might my child be seeing when they look at me?"

There's a few different ways I approach it. One is tell to parents to look at the kernel of truth. Your child may say something like, "Well, you were always so critical, you were always involved in your work," or the like. And to not really get into the rightness or wrongness of it, to find some kernel of truth. Typically, in the same way that our spouses or romantic partners have a kernel of truth in their complaints, adult children have kernels of truth, if not whole bushels, of truth in their complaints about us.

A lot of my work is helping parents disentangle themselves from the shame and hurt and rejection that they feel when their adult child first starts to have this dialogue. Which, generally, isn't until they're adults and often doesn't start out as an estrangement. It may start out as a result of going into therapy or reading something, that kind of thing.

The parent has to be able to tolerate their own feelings of fear and guilt and anxiety and defensiveness, particularly if that parent was a much better parent than their own parent was. A common source of tension between today's boomer parents and their millennial or Gen Z kids is that the parents, in many ways, have provided their children with a much higher quality of life, in terms of what they paid for or the kind of experiences that they provided them. I'll often hear parents say, "Oh, you think you had a hard childhood? No, no. Let me tell you what a hard childhood is." Which, of course, brings the conversation to a grinding halt.

It also reflects one of the things you talk about in the book — how we got to this place where estrangement is an option, and what has led to this culture of estrangement, for good and bad. There are certainly legitimate reasons to cut oneself off from one's parents or from one's adult children.

I think it's a number of different things. Anthony Giddens talks about pure relationships. In late modernity we no longer have the institutional markers of identity.

We're no longer defined in relationship as much, in marriage, church, neighborhood, etc., detailing how we're supposed to act. Identity has become much more important. There's been this enormous rise in individualism that's been tracked and it continues to rise even in the past few decades. If you look at the way that boomers define themselves as individuals, it's very different from, say, how the millennials or Generation Z define themselves as individuals.

A rise in individualism is hugely important. Divorce is hugely important. In my survey of 1,600 estranged parents that I did at The University of Wisconsin survey center, I found that more than two thirds of the parents who were estranged were divorced from the child's other biological parent, and the estrangement happened after the divorce. Some of those divorces happened when the parents were in their sixties or seventies, even.

There's a bunch of different ways that divorce increases the risk of estrangement. One is just that it can cause one parent to poison the child against the other parent. It can cause the child, independently, to blame one parent over the other or, "You're the one that broke up the family." It can bring new people into the family home — step-parents, step-siblings to compete. And in a highly individualistic culture like ours, it can cause any child to see the parents more as individuals with their own relative strengths and weaknesses and less as a family unit that they're a part of.

I think the rise in therapeutic culture is also hugely important, that we define ourselves in the language of therapy and needs. I think there's an overemphasis on thinking about family and family dysfunction as a cause of an adult outcome. There's this great quote by cultural sociologists Eva Illouz where she says that today, our realities are plotted backwards. With a dysfunctional family, it's a family where your needs aren't met. How do you know that your needs weren't met? By looking at your present condition.

In other words, the therapeutic narrative of today's culture is to cause people to assume that whatever their anxieties, dysfunction, depression, liabilities in adulthood are, can be reliably traced to childhood. In some ways, of course, that's true and should be. But in many cases, it's not. Research shows that a large part of today's fringe, particularly in Generation Z, their anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, can be traced to just being born at a certain time period. Genetics are important. All of those things, I think, are hugely important. And finally, the political, tribal climate in today's society. I'm seeing many more estrangements in the era of Trump that are just based on political differences.

That brings us to something else — the "all or nothing." You're all in or you're not in at all. That the idea that maybe there are ways of compromise and setting boundaries and saying, "Dad, you and I have a difficult relationship and maybe we can come to some sort of civil detente. This is the depth of a relationship we can have and we can get something fulfilling out of that for all sides." As opposed to, "You know what? You're cut off. That's it, I'm done."

The problem is that our culture has lionized that act. It's considered to be an act of existential courage or strength to say, "I'm just getting rid of all the stressful people, I don't need the drama." There's enormous social support for that. That somehow, you're positioning yourself as being more strong or courageous or vital in a way that is really problematic. I also think you can just as easily make an argument that you're not being existentially courageous. In some ways you're being much more cowardly because you're not really facing the people or the anxiety that is evoked or the other feelings that is evoked in the present.

Obviously, it's a particular group of parents that contact me. They want help. A lot of these parents, they're willing to basically do just about anything to reconcile with their children. A lot of them are reasonable people and I think their adult children are missing out on what could be a good confidant or family member or other resource because the adult child is not willing to just have the dialogue, just even do family therapy. But there's two sides to the equation. Some parents have been so blaming, critical, rejecting for such a long time that the adult child feels like, "Well, screw you. Now you want to talk and figure it out? I don't think so. That ship has sailed."

It's important to also emphasize sometimes there will be a mental health issue or substance abuse. And it's also in the parents' interests to respect that boundary because it's important for them as well.

The mental illness is such an important thing for there to be more discussion about in the public. Certainly a not-insignificant number of estranged parents who contact me, their kids are mentally ill, and some are dramatically mentally ill. Others are homeless or drug addicted and the like and these parents, they're just really faced with a double burden of not only not having contact with their kid but that ongoing day-to-day, sometimes minute, worry of, "Is my kid alive? Are they having a psychotic break somewhere?"

As you make clear in the book, there isn't necessarily a happy ending for everyone, or something that works for everyone. I want to also touch on what happens sometimes in marriage or in relationships. A person winds up in a relationship with someone who is isolating them. It also speaks to the potential that a parent has of seeing someone getting in a toxic relationship. The powerlessness of that has got to be intense.

That's huge. I don't have any great statistics of that but in terms of the parents who contact me, it's a very significant percentage where the parent will say, "Prior to my child getting married, we had a really close relationship." They'll send me copies of cards, like "Best Mom Ever," or "Best Dad Ever," or some long letter of gratitude. A year or two later, they're estranged because their new husband or wife doesn't like them. Sometimes, of course, that may come because the parent doesn't like that son-in-law or daughter-in-law to be, or says something critical or negative and the problem is with the parent. But not always. Just as often, it's because the son or daughter married somebody who's really troubled or really controlling and basically says to the adult child, "Choose them or me, you can't have both." That's a significant problem.

What do you advise parents who are in that particular situation? If my daughter was in a relationship with someone like that, I would be very afraid that she was in danger.

The answer is, you have to proceed with absolute caution because part of what you're up against is your adult child's powerful desire to feel like they're in charge of their own life and they can make these decisions themselves. I you go up against that too powerfully, you're going to drive your child into that person's arms.

What I always tell parents is that new romantic partner is the gatekeeper to your child. You can't go around them. You can't try to have a separate deal with your kid — and by "kid" this could be a 60-year-old. You can't go around that person, you have to go through them. If you're going to send your child a birthday greeting, make sure you send them one to the partner. The more troubled they are, the more you have to be mindful that your goal is not to alienate them. One of the big things that I work on strategically is for parents to write a letter of amends. I encourage parents to write one to the troubled son-in-law or daughter-in-law, not so much that I assume that they're going to relent but for the audience of their own child. So that their own child can feel like, "Okay, my parents are doing everything possible, let me see if I can use that to advocate for a door opening."

But to return to your question about, "Let's say my 21-year-old is getting involved with somebody that's dangerous," you still have to be in a position of consultation, not management. Which is, ideally, what we shift into when our kids become teenagers. We're really a little bit behind them but we're not trying to shake them by the shoulders unless we have the luxury of having that kind of relationship with them. Most of the time, we don't, so we have to just say, "Well I've noticed this. Is that something that you've seen as well? Do you think that that's a problem?"

You also have to watch your adult child to see how allergically they're responding to those kinds of inquiries. The last thing you want is for your kid to stop talking to you. You're better off having a kid who will keep talking to you and you're tolerating your anxiety that the relationship is not a good or right one and maintaining open lines of communication than them feeling like, "I'm just shoving this down because my parent's just going to make me feel too guilty or controlled."

People have siblings, they have step-parents, they have in-laws, they have grandparents. It's a much more complicated dynamic where maybe one has become estranged but the rest aren't. How do you advise and counsel families about this? As you talk about at length in the book, this also then gets into money. This gets into inheritances. This gets into who is the favorite child and who is not, an siblings become estranged from each other, obviously. How do you negotiate that in a way that is loving and caring and equitable?

Parents have to be role models of taking the high road. Let's take the case of you've got three children and one's estranged and the other two aren't. It's not uncommon that the non-estranged siblings will be really mad at the estranged sibling, particularly if they feel like the estranged sibling's rewriting history or viewing the parents in a really unsympathetic way. What I tell parents is you have to show leadership to your children and the rest of the family. You have to show empathy for your estranged adult child. You can say, "She feels like we weren't good parents or that we were hurtful to her. Obviously, our memories are somewhat different," assuming they are. If they're not, then parents should just be as explicitly honest with the people that they're close enough to be honest with. Because kids do come back sometimes.

Sometimes, siblings, they're only estranged from the parents and they're not estranged from the other siblings. If the other sibling says, "Well, how are they talking about it?" If they say, "Oh, they're acting completely victimized and martyred, that's not going to really set the stage as saying, "They're really talking to figure it out and be sensitive. They really want to repair and they're working on themselves."

And often, not always but often, the truth or some version of it rights the ship again.

When estranged children estrange themselves, some clearly do if it's a clear case of abuse or neglect. But people sometimes estrange themselves for reasons or feelings separate from good parents. They don't know any other way to feel like they have a boundary or a claim on their own lives than to cut off the parent. Parents can approach them with compassion, with empathy and with an assumption that they're trying to work on something or master something in doing this and not just view it in a victimized light. What I always tell parents is, "Don't say to your child, 'Why are you doing this me?'" Say, "I know you wouldn't do it unless it was the healthiest thing for you to do," because that's what it feels like to them. I think the more family has that perspective, the more likely a reconciliation is to occur.

Shares