Suddenly, the Mafia was everywhere in my life. The podcasters I listened to were constantly joking about and referencing Scorsese's mob movies. My Gen Z housemate and her friends were binge-watching "The Sopranos" — a show that came out when she was two. The leftist Instagram posters I followed were dense with screencaps from "The Irishman" and "Goodfellas." The Harper's magazine on my coffee table had a Scorsese story on its cover. And most crucially, the people I followed on Twitter — a cross-section of what you might call The Very Online Left — was awash with jokes and memes about Mafia-related movies and shows.

Sometimes, cultural trends start randomly, as if the entropy of the universe were jostling artifacts off their shelves. The rise of Hush Puppies shoes in the 1990s, for instance, has been attributed to random influencers deciding they were suddenly cool. In other cases, however, trends come about for complex social reasons that relate to our political moment.

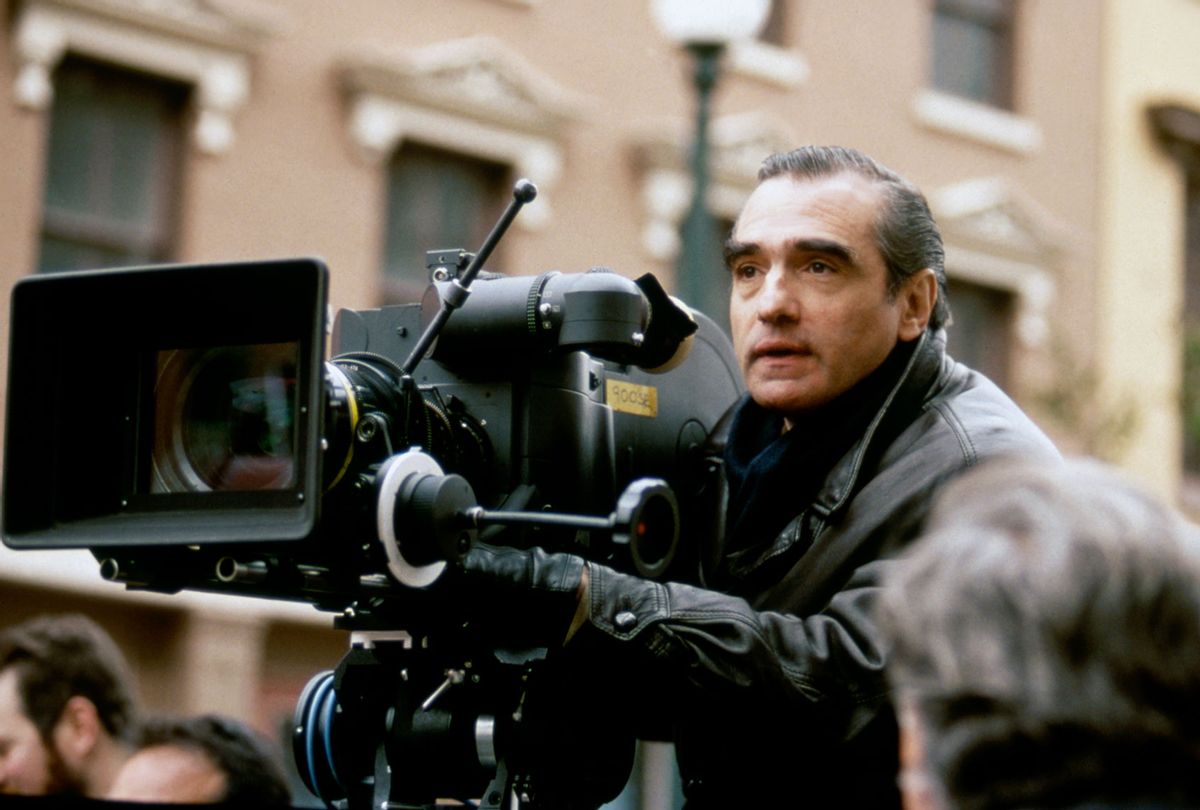

I'd thought that the sudden Scorsese renaissance was a case of the former: his movies are well-shot, well-acted, well-directed, and hearken back to beloved filmmaking tropes of the New Hollywood era. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that it was the latter. There are deep political reasons that young Americans, particularly those like me that are left of liberal, are swallowing the Scorsese pill right now.

When I talk about Scorsese being everywhere, I should clarify that I'm mostly talking about his mob movies — "Goodfellas," "Mean Streets," "The Irishman," "The Departed," "Casino" and so on. Yes, the man can make an incredible kids' film ("Hugo"), but that doesn't seem to be what's on the mind of the zeitgeist. It's the Mafia movies that are most resonant.

It might seem odd that organized crime flicks would resonate with the American left. After all, mobsters aren't exactly the paragon of revolutionaries. Most mobsters, both in real life and on-screen, are generally capitalists of the black market ilk: business owners who exploit their own workers, and have little compunction for their worker's own rights or freedoms. What could explain the sudden fascination of my political cabal for these type of characters?

Of course, a mob movie — like a superhero movie — isn't merely a film about mobsters. These movies, at least through the lens of someone like Scorsese, are larger stories about a group of friends (often very close friends) working together as a community, supporting each other, and undermining the state and its intelligence apparatuses — even, if their capers are successful, circumventing it. There's something faintly politically recognizable in those themes, particularly the subversion of the state and the camaraderie of one's fellow gangsters.

As a leftist and an anti-capitalist, I can say definitively there isn't a lot of positive representation of my kind in mainstream cinema ("Sorry to Bother You" being the very, very rare exception). That's to be expected: executives of media corporations, like most capitalists, aren't eager to greenlight movies about how rich people like them shouldn't exist.

But we're in a weird political moment, where the capitalist system is apparently collapsing in on itself and America is on the verge of becoming a failed state. Citizens of the Western World seem to know this on a subconscious level, but those who haven't accepted the reality sublimate it, and see it transformed psychologically into and through other objects.

To wit: The global rise of xenophobic nationalism, which Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, and Jair Bolsonaro all epitomize, embodies voters' regressive reaction to the failure of liberal managers of capitalism to maintain our standard of living over the past decades as the rich looted the commons. QAnon is a mass sociological delusion among those who can't accept that their populist leader was a fraud. And the "resistance liberals" of the past four years — who, I must note, are far to the right of what I speak of when I speak of "the left" — deluded themselves as to why someone as odious as Trump was able to rise to power, scapegoating Russia rather than confront the plummeting standards of living that had resulted from decades of unfettered capitalist accumulation.

Consciously or not, we're all looking for answers as to why things are so bad, and never seem to change. That means that all kinds of seemingly unrelated political phenomena stem from the shared wish to see an alternative to capitalism, or at least a return to some imagined "normal" existence. And on a visceral level, all of the above groups wish to see those whom they believe responsible for wrecking our future brought to their knees.

Consider, for instance, the public delight over the recent "GameStonk" debacle — in which retail investors organized on Reddit to drive up the price of GameStop stock, which many hedge fund managers had short-sold believing the price would fall; the result of GameStop's skyrocketing price was that these hedge fund oligarchs lost billions. Seeing Wall Street goons lose millions was a source of much online mirth, a joyful reaction to the common sentiment that we live in an undemocratic oligarchy in which we have no control. The public excitement over GameStonk was relatable: screwing over hedge fund assholes by using their own financial tools against them felt like a blow, albeit minor, against the goliaths who rule and fool us.

Of course, in reality, the Gamestonk incident wasn't really a case of little guys defeating the big guy: far from being proletarian leaders, those with the privilege to trade thousands of shares of stock tend to be middle-class or richer. Moreover, retail investors are not an oppressed caste, and their politics are not necessarily aligned with the global working class. Still, the GameStonk incident was the only incident in recent memory in which oligarchs suffered some kind of retaliation for destroying the planet and the middle class. For that reason it inspired great glee among onlookers.

Something similar can be said about organized crime cinema, in that it also depicts a David versus a Goliath. Hollywood is bloated with stories about future capitalist dystopias, because that's all that the capitalist imagination can envision: a depressing future with more oppression, or the status quo. Crime cinema is a way through, a subtle play on how a group of "revolutionaries" might interact with the world and try to win it back from those who uphold a rotten status quo in which their source of income is shut out. After all, what is a revolution besides a group of paranoid, cool guys and gals who hang out together, own a lot of guns, and try to do illegal things while the state's intelligence agencies try to stop them?

The idea of leftist themes being subtly "laundered" through other pop culture genres is not a new idea. In 1979, famously abstruse Marxist literary critic Frederic Jameson said something similar about "The Godfather." In an essay he wrote for Social Text, Jameson says he disagrees with the vulgar notion that such big-budget commercial flicks are void of larger political themes. Rather, Jameson posits that such art often has a hidden "psychic function" — often, the mass yearning for, say, freedom from capitalist oppression, which will be shunted through the clumsy artistry of big-budget action or adventure movies. In other words, the soiled masses need a cathartic outlet for their class-based rage, lest they explode and revolt against the elites.

Multinational media corporations produce entertainment that offers a "psychic compromise," Jameson says — media that "strategically arouses fantasy content within careful symbolic containment structures which defuse it." In other words, you, the media executive, give people something to yearn for and connect with, and it prevents them from coming at you with pitchforks.

As for "The Godfather," Jameson sees the film as a larger twofold metaphor. "When indeed we reflect on an organized conspiracy against the public, one which reaches into every corner of our daily lives and our political structures to exercise a wanton ecocidal and genocidal violence at the behest of distant decision-makers and in the name of an abstract conception of profit — surely it is not about the Mafia, but rather about American business itself," he writes. In "The Godfather," the mob, then, is a metaphor for a universal political sentiment.

But that movie is also about family. Jameson noted the utopian element in the tight-knit Corleone family — "a figure of collectivity and as the object of a Utopian longing." The ethnic element, of it being an Italian family, symbolizes an old-fashioned ideal of "ethnic neighborhood solidarity." For most of us in atomized capitalist societies, such tight-knit communitarian bonds are unfathomable. Would any of your friends help you bury a dead body?

Thus we can watch the mobsters in "The Departed" outwit the South Boston cops and perhaps cheer for them; but, we'll never see an action film in which the Bolsheviks rob a bank to fund the revolution (at least not one funded by Disney or Paramount). Still, Hollywood gives us a few pointed examples of mobster comrades subverting the state, chilling and drinking with friends, and sticking it to the man — and for now, that will have to suffice.

Shares