After her passing at the end of 2020, obituaries celebrated Joan Micklin Silver's pioneering directorial work on feature and made-for-television films like "Hester Street" (1975) starring Carol Kane, "Bernice Bobs Her Hair" (1976) starring Shelley Duvall, and "Crossing Delancey" (1988) starring Amy Irving. In the Los Angeles Times Mark Olsen pointed out that "with the recently renewed focus on female filmmakers in Hollywood, Silver's work has enjoyed revived interest in recent years." However, discussions of Silver's career routinely ignored some of the gems in her filmography: the highly original, progressive, and delightful educational films she made in New York City at the start of her film career in the early 1970s.

Silver learned how to write and direct while making these classroom shorts, and because she produced them in the city — often casting friends and family members, shooting on location in Central Park and in friends' apartments — they capture some of the long-gone spirit of the city in this era. Her New York Times obituary briefly mentions one of these, "The Immigrant Experience" (1972), a social studies film that she made in partnership with producer Linda Gottlieb for Learning Corporation of America (LCA), Columbia Pictures' educational film division. Gottlieb, who went on to produce "Dirty Dancing" in 1987, and Silver formed a production company, Omaha Orange (named for the cities in which each was born), drawing from the people and places around them for the stories they collaborated on. Two wonderfully unconventional films Silver wrote and directed for LCA in the early 1970s—"The Fur Coat Club" (1973) and "The Case of the Elevator Duck" (1974)— deserve a place alongside Silver's later feature film work, offering viewers today a cheery, fantastical counterpoint to Fran Liebowitz's decidedly more curmudgeonly recollections of the era currently streaming in Martin Scorsese's Netflix docuseries.

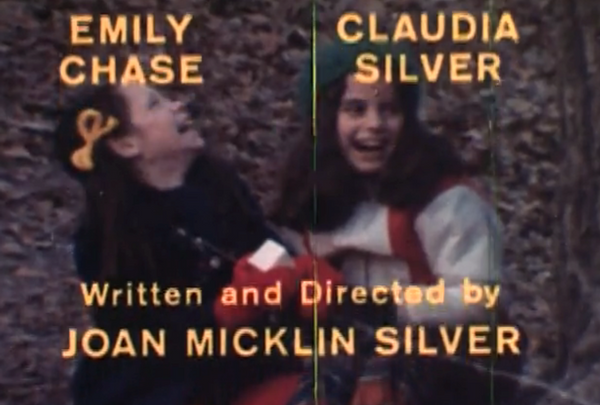

"The Fur Coat Club" (1973)

"The Fur Coat Club" (Learning Corporation of America/Joan Micklin Silver)

"The Fur Coat Club" (1973), which stars Silver's nine-year-old daughter, Claudia, and her real-life friend Emily Chase, wordlessly depicts two young girls scampering around the city in a friendly competition to see who can touch the most fur. The girls are fearless, brushing up against strangers as they pretend to look admiringly into a baby carriage while petting a mother's fur-coat-clad back or slithering between strolling Upper East Side ladies to cop a feel. They keep score of who is getting the most fur touches, taking turns in the lead. When they find but are ejected from fur fetish heaven, Mr. Paul's Fur Shop, they cleverly figure out a way to sneak into the store only to end up being accidentally locked in the fur vault overnight. This is the only scene in the film in which tears are shed, as the girls realize that they are stuck and the furs no longer seem like such fun company. The fur vault scene is shot in the style of a horror film, complete with screeching music, rapid cuts as the mink stoles appear to come to life and attack the girls, and quick inserts of an ominous taxidermied monkey face. But the girls soon realize that this is only their imagination, and so they snuggle up and go to sleep.

A pair of leather-jacket-clad burglars break into the vault, a potentially terrifying moment that Silver disarms with her humorous approach: the girls welcome the thieves with hugs of relief delivered out of gratitude for having liberated them from the fur dungeon. When she realizes what's going on, however, Claudia craftily slips one of the burglar's guns out of his holster and, cartoon-style, thwarts the robbery. When the police arrive, the girls are welcomed as heroines and get to literally thumb their noses at the bad guys. Having now had their lifetime fill of fur, when Mr. Paul arrives at their apartment the next day with a pair of white fur muffs as a token of his appreciation, they put on fake smiles and give the muffs to their younger siblings. The girls have left their fur fetish behind and embark upon a new hobby: spying on the conversations of Central Park lovers with a delightfully analog system of bright red plastic walkie talkies adhered to a park bench with masking tape.

Gottlieb and Silver were inspired to make the film by contemporary stories featuring mischievous, irreverent, and adventurous girls, like Louis Fitzhugh's 1964 young adult novel "Harriet the Spy," about an 11-year-old Upper East Sider who writes about people's doings in her espionage notebook; and the 1965 movie "The World of Henry Orient," in which obsessed teenage girls follow a concert pianist (Peter Sellers) around New York City. "The Fur Coat Club" also had personal roots: its plot was inspired by Claudia's real-life fur coat club, a game she invented with her best friend (when I interviewed Claudia in early 2021, she assured me that she never got locked in a fur vault; that part of the film was her mother's fabrication). Claudia, whose literary obsessions at the time included Nancy Drew novels and Madeline L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time," remembers that she would give her friend "the eye" before trying to rub up against one of her easy-to-locate targets: the endless parade of Upper East Side ladies in furs walking the neighborhood's streets. For the shoot, not only did she and Emily get to miss school under the pretense of being sick, but they got to spend these days going around New York City "feeling for coats," a "super fun" experience for a grade schooler. Claudia remembers the hilarity of shooting the fur vault scene during which the girls were encouraged to really ham it up with exaggerated facial reactions because the film had no dialogue. "Mom was a good director," Silver recalled. "She knew how to get it out of you."

The film gave its grade school audiences a glimpse of independent girlhood, modeling an inquisitive sense of play in the city that is hard to imagine now in our buttoned-up, fearful modern-day world. Looking back at "The Fur Coat Club," Claudia Silver commented that "the world is so protective now, with so many rules. One of the charms of the movie is that it is free and exciting, almost fairy tale-ish." It was also innovative: from its largely visual storytelling to Silver's resourceful use of non-actors — including fur-coat-owning friends like Fresh Air Fund chairwoman and prominent trustee of the New York Public Library Sue Newhouse, who plays the glamorous and untouchable lady in white in the film, and Mr. Paul, who plays himself in the scene shot in his fur shop — showing Silver rising to meet production challenges on a small budget.

"The Fur Coat Club" (Learning Corporation of America/Joan Micklin Silver)

The film also hints at some of Silver's socially progressive ideals. When Claudia rubs up against the back of what she presumes is yet another white woman in a fur coat bending over a drinking fountain in the park, it turns out to be a Black man instead. Looking down at her in a low angle shot from Claudia's perspective, the man smiles warmly. Claudia smiles back and then goes in for some non-furtive extra fur rubs before the two high five and she goes on her way in search of her next feel. When the police arrive at the fur shop, a Black officer is the one who gently interacts with the girls. These might seem like insignificant moments, but they were certainly intentional and important in their small way: at a time when school integration was still being debated and when social and racial unrest was peaking, such easy moments of easy interracial interaction were normalizing, not just in a place like New York City, where the film was made, but in the far corners of the country to which it traveled through the powerful conduit of the classroom.

Watch "The Fur Coat Club" below:

But why was this film made? Adults often ask this question after seeing "The Fur Coat Club," as film collector Skip Elsheimer of A/V Geeks Educational Film Archive likes to acknowledge when he shows the film at his 16mm screenings, which he often does since it is one of his personal favorites from his over 25,000 film collection. I recently asked a seven-year-old to watch the film and wanted to know if she thought the film was trying to teach any lessons. Her answer was no, because "the girls didn't change" — they just move on to their next equally mischievous game. This is certainly part of the charm of the film: the un-cynical way it captures the spirit of childhood. I asked Linda Gottlieb the same question, and she said that she couldn't imagine why William Deneen, the head of LCA, actually allowed them to make such an offbeat film. Gottlieb recalled that she and Silver really just wanted to show smart girls navigating the world, encouraging kids who would eventually watch the film to be creative and have fun. They were not interested in making a film that was "message driven."

Luckily for them, LCA was actively seeking out open-ended and un-didactic films at the time, and so Omaha Orange got greenlit to complete the project. The film's study guide questions, which aimed to help teachers incorporate films into their curricula, included a series of standard issue viewing comprehension questions ("How many different ways can you remember in which people reacted to the girls' tactics?"). But it also laid out the ways that teachers might use the film to inspire creative reactions from their students: "Write a story about, or draw a picture of, 'The Thing I Love Most to Touch'" or "Tell this story as if you were the girls, the furrier, the fur-coated woman with the baby carriage, the robbers."

"The Case of the Elevator Duck" (1974)

"The Case of the Elevator Duck" (Learning Corporation of America/Joan Micklin Silver)

Based on a children's book of the same name by Polly Berrien Berends, "The Case of the Elevator Duck" (1974) departs from the Upper East Side to bring viewers inside a New York City housing project. The film is focused on a charismatic African American boy (Silver's ability to direct youthful non-actors in both of these films is notable) who fancies himself an undercover detective and sees the world through this imaginative lens. Gilbert's life takes a turn when, during one of his patrols, he encounters a duck that has mysteriously wandered into his apartment building's elevator. The building doesn't allow pets, but Gilbert can't resist its charms and decides to take care of it, at first hiding the duck in his hamper and letting it out for floats in the bathtub. When his mother discovers the duck, she gives detective Gilbert two days to find its owner — since there are no pets allowed in the projects, no exceptions, she is not going to risk their safe housing for the sake of a wayward bird.

After he evades some close calls with the building's dedicated security guard, Gilbert sleuths about to find the duck's home. Like "The Fur Coat Club," "The Case of the Elevator Duck" has a zany sense of humor. At one point Gilbert bemoans having taken on the duck's case when instead he could have taken on "something more routine, like a mugging." But he sticks to it and finally cracks the case by taking the duck to each floor of the building and letting it lead him to its apparent home. As it turns out, the duck had been residing with Julio, a Puerto Rican boy who is a little younger than Gilbert, whose older sister won't risk eviction either, shuttling the duck back into Gilbert's care. Frustrated at seemingly every turn, Gilbert finally lands on an ingenious solution: he brings the duck to the neighborhood's day care center, where there are no rules prohibiting animals and where all of the kids can enjoy its company, Julio included.

As with the girls in "The Fur Coat Club," Gilbert is resourceful, persistent, independent, and a creative problem-solver. His barrier to keeping the duck as a pet may have been specific to the rules of life governing his housing project, but his solution represents something universal: not getting discouraged by failure and finding inventive ways to problem solve. "Man," he proudly says with a smile on his face after he solves the case, "I'm gonna go crazy with all of the ideas I'm getting."

Gottlieb recalled that when they were auditioning for the lead they were immediately impressed with Robert Lee Grant, who was cast in the role of Gilbert. He was confident and charming, a natural. At the end of his audition Gottlieb asked him how he felt about ducks, and Grant responded that he loved them. On the first day of the shoot, when the two ducks — one star, one alternate — showed up on the set, it turned out that Grant was in fact terrified of ducks, a fear that he fortunately surmounted during the course of filming. Gottlieb remembered one particularly difficult four-hour shoot that involved trying to get the duck to walk into Julio's apartment. Gottlieb laughed as she asked, "How do you get a duck to turn left and go in a door?" They tried everything they could think of: food, verbal coaxing, someone from the prop department tying an invisible string to the duck's legs to steer it into the apartment (which looked like a duck being pulled by an invisible string into an apartment). Someone had the idea to try a water gun, and so a crew member off camera shot water at the duck from behind, and lo and behold it walked inside the appropriate apartment. Gottlieb and Silver vowed never to work with ducks again.

Watch "The Case of the Elevator Duck" below:

Like "The Fur Coat Club," "The Case of the Elevator Duck" lacks an obvious lesson; it does not seem to be teaching its viewer anything in particular. But it depicted a smart, curious, and imaginative Black boy solving problems on his own, helping his neighbors, and being kind to an otherwise helpless creature (he expresses fear about the duck being put to sleep if it ends up at the pound or ending up "in a pot" for someone's dinner). Gottlieb didn't believe in dry instructional or "message films," which is evident throughout the LCA catalogue, over which she wielded significant influence. Take, for example, the highly successful social studies films that she produced. Instead of delivering lessons these films told stories, conveying culture and context in a way young people could easily relate to, as in Bert Salzman's "Angel and Big Joe," about a migrant worker and a telephone lineman (played by Paul Sorvino), which won an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film in 1976, or Michael Ahnemann's "Siu Mei Wong: Who Shall I Be?," about an aspiring Chinese American ballet dancer. Dramatic films, Gottlieb reminded me, were also savvy from the business end: they could be marketed to different teachers, in this case to social studies as well as English, thereby generating more sales and rental revenue.

Claudia Silver recalls that her mother was proud of the films she made during her time at LCA, and was especially fond of "The Fur Coat Club," no doubt partly because it also functions like a home movie, capturing her spunky daughter playing one of her imaginative youthful games. Claudia remembers her and her classmates' delight when her mom showed "The Fur Coat Club" at her private girls' school. Watching the film now brings to mind the freedom she felt as a young girl in the city, the experience of exploring New York as well as getting in and out of trouble on her own. Silver concedes, though, that the film presents this in fantasy form: she was, in fact, not allowed in the park alone, even with a friend, until she was at least 11 or 12.

Those who look only to Hollywood as the gold standard for evaluating a filmmaking career might deem these films inconsequential. However, they were important in a number of ways. They helped shape the values and creative lives of the kids who saw by showing them a diversity of young people who were competent and resourceful. The National Council of Teachers of English conducted a 1978 study to determine what classroom films fourth and fifth graders best liked watching. Out of the 24 short films they were shown for the study, "The Fur Coat Club" and "The Case of the Elevator Duck" were ranked No. 1 and No. 2 respectively.

Film companies like LCA were also incubators for Hollywood talent. Many future directors, actors, writers, editors, and camerapeople cut their teeth in the flourishing nontheatrical industry. Given the paucity of women directors in Hollywood in the early 1970s, this was an especially important segment of American film production for women who wanted to learn the business of filmmaking. Gottlieb doesn't recall specifically looking to give women opportunities at LCA, but she acknowledges that as a young woman in a powerful position at LCA that she was drawn to people like her (the old boys network, of course, works the same way), and usually hired female assistants to scout for new talent and projects. This is precisely how Joan Micklin Silver got her first break at filmmaking, which allowed her to push her way into the firmly male territory of Hollywood in the 1970s when she was ready to take her talents to the big screen. "By the time she came to do 'Hester Street,'" Gottlieb told me, "she really knew her craft."

Shares