Not only do we humans struggle to manage our trash on Earth — it’s a problem in outer space too.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), the total mass of all the man-made space objects in Earth’s orbit is more than 9,200 metric tons. Statistical models estimate that there are 34,000 objects greater than 10 centimeters crowding our planet, 900,000 objects between 1 and 10 centimeters, and 128 million objects between smaller than 1 centimeter. As more satellites make their way into our orbit, the immense amount of space junk poses a serious issue for potential collisions or inhibiting the function of these satellites.

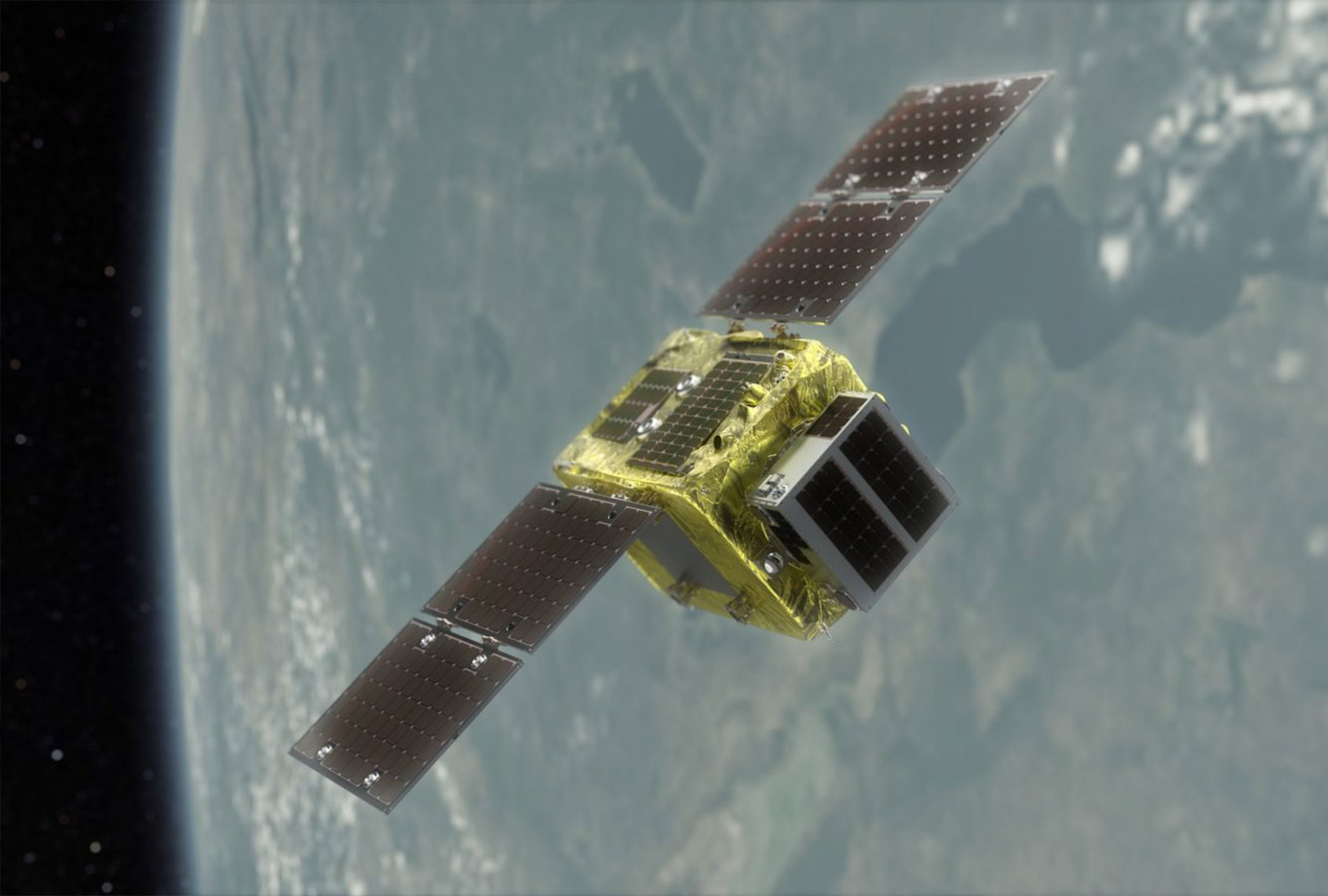

This is why a spacecraft named ELSA-d (which stands for End-of-Life Services) was launched on Monday morning from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Its mission is to test a way to clean up space debris. Specifically, ELSA-d will attach itself to future dead satellites and other space junk and then proceed to push them toward Earth so that they can burn up in Earth’s atmosphere, acting as a space janitor for man-made orbital debris.

Notably, the spacecraft is not designed to capture dead satellites already in orbit, but rather future ones that would be launched with compatible docking plates. The mission that started today is part of a test to see if the two satellites are up for the job.

According to the mission’s web page, ELSA-d consists of two space crafts: a servicer satellite and a client satellite. The servicer satellite will use its magnetic docking mechanism to target and rendezvous with the client satellite. A private Japanese company called Astroscale is behind the mission that will eventually target debris and push space junk toward Earth’s natural incinerator.

This is a very tedious catch-and-release dance to do in space, John Auburn, Astroscale’s managing director in the United Kingdom, explained to NBC News.

Want more science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“It’s enormously complex because you have to exactly match the motion of the spacecraft you’re docking with,” Auburn said. “When a spacecraft docks with the International Space Station, that’s a very controlled maneuver. But if you’re trying to dock with a failed satellite, it could be tumbling and you have to very slowly come together almost like you’re doing a dance.”

But if these satellites can stick the dance, it could be a viable solution to a growing problem in space.

“This is an issue like plastics in the ocean,” Auburn said. “We’ve been working for eight years to turn a difficult problem into a business.”

As Salon has previously reported, there is a growing conflict between the interest of the business world and science. More satellites, like the ones being launched by SpaceX, means more pollution and garbage in space. This not only could affect astronomy research from ground-based telescopes, but it could also increase the risk of collisions from other satellites, both commercial and scientific, in similar orbits.

Scientists fear that if enough satellites collide, it could cause a chain reaction as thousands of fast-moving shards envelope other satellites, creating a cascade of more shards and thus more collisions ad infinitum. That scenario is known as Kessler syndrome, so-named for the NASA scientist who theorized it. While the destruction of human satellites would affect commerce, research and communications, the worst-case scenario would involve the loss of human life if, say, the International Space Station or other future space stations were destroyed. The International Space Station has been struck by debris before, including 2016 when such a collision cracked a window.

Satellite collisions have happened before, but not to the extent that any caused a chain reaction. In February, 2009, two satellites collided — an active Iridium 33 satellite which was operated by U.S.-based Iridium Communications LLC, and Kosmos 2251, a decommissioned Russian satellite. There were reports of bright lights in the sky over Kentucky, and loud booms from satellite debris falling into the atmosphere. Two years prior, China destroyed one of its own satellites in low-Earth orbit as part of a test. Shortly thereafter in 2008, the United States tested a similar anti-satellite weapon by destroying a defunct satellite, a move widely interpreted as a chest-thumping rejoinder to China’s anti-satellite missile test in the ongoing cold war between the two nations. Both of these events created a fair amount of space debris in their wake.

Aaron Rosengren, an assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California–San Diego, told NBC News that cleaning up space junk will be critical for the future of other space missions.

“Even though space is big, the usable orbits where we keep our satellites are quite small,” Rosengren said. “If we have a higher and higher density of objects in these very narrow regions of space, that will lead to more collisions over time.”