I watch too much true crime, so I know how it goes. There is a particular type of crime story that is supposed to be more gripping than the others. It's the story of violence befalling the quiet person, in the quiet family, in the quiet town.

"This was supposed to be a safe neighborhood!" the host exclaims, passing his shock along to the viewer like a closed circuit. "These types of things don't happen here," the officer who investigated the case confirms breathlessly, desperately trying to make her work appear more skillful and elaborate than it was.

Beyond the scandal and drama inherent in conjuring such personal trauma into a piece of entertainment, I'm most interested by the unspoken questions this framing provokes: "This neighborhood was supposed to be safe for whom?" "Where do these types of things happen, and why is it more acceptable to happen there?"

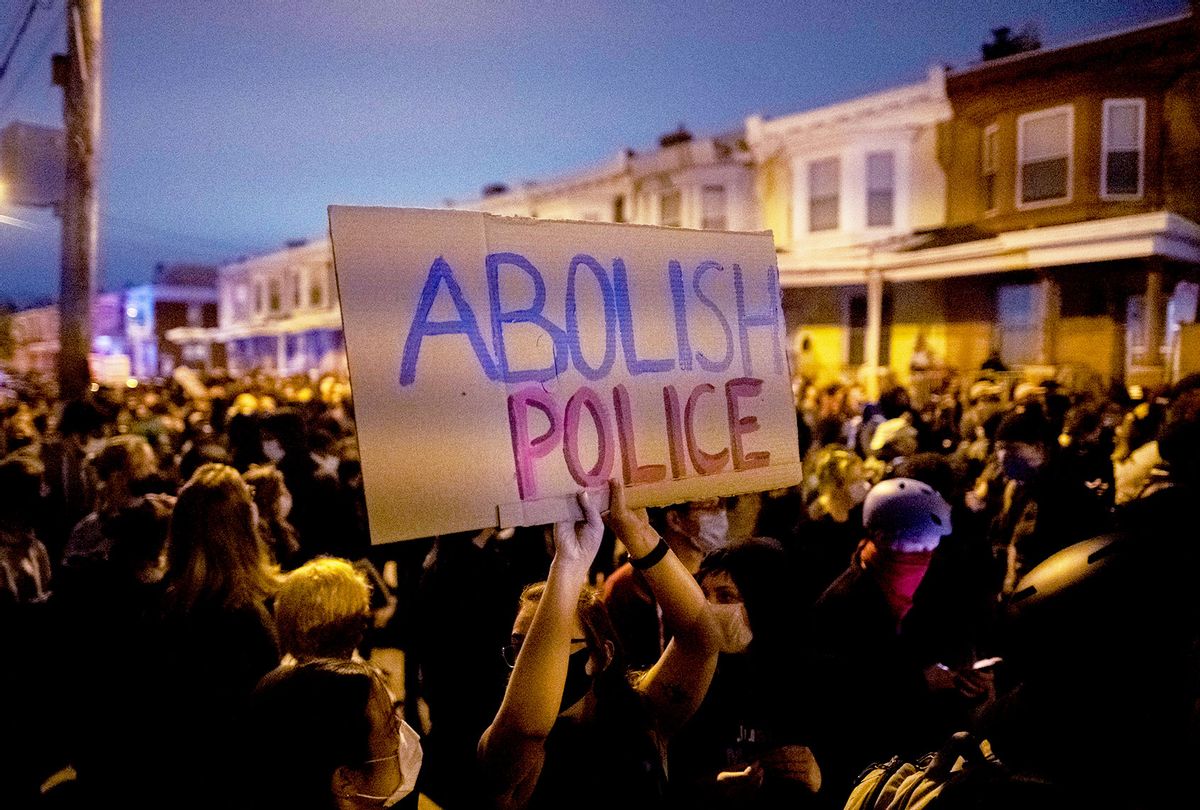

These are also the questions guiding my work toward a world without police and prisons. I believe they hold the answer to another question that often meets calls for prison/police abolition—"Who will keep us safe in a world without police?"—because they illuminate that safety is not a universally recognized phenomenon, as much as it is pretended to be. The meaning of safety depends on what exactly you find worthy of protection, and police and prisons are only understood to keep people in general safe because this society generally deems a particular group of us unworthy.

But there is another way to think about safety and protection, and police abolition demands it.

According to my realtor, I live in a "safe" neighborhood — by which he means at least heading in the direction of the neighborhood featured in that gripping "Dateline" special — where "there is a police station right around the corner!" I live in a neighborhood where gentrification is metastasizing more quickly than you can say "kombrewcha," where those police officers around the corner go out of their way to fine and throw Black people in jail just for living in a pandemic. I live in a neighborhood where most Black people can't afford the steadily increasing rent, where the clusters of homes Black people are able to hold onto amid pressures from banks and landlords become COVID hotspots quickest, and the people who live there die of the disease at much greater rates.

When a person asks, "Who will keep us safe in a world without police?" I think about how I have never felt "safe" as a Black person in the places police make "safe," and I am not even one of the local poor people who is most targeted for clearing away. To be "kept safe" in this way is only for the necks of Black people to be kept safely under the foot of everyone else.

Admittedly, this is a macro level understanding of safety that doesn't necessarily address the everyday threats that most people — including many Black folks — rationally fear coming to pass if policing were to disappear. It's true that people in our community aren't always kind. We aren't always peaceful or forgiving, even when we should be (and we shouldn't always be). It's true that without police, we would sometimes get into violent conflict — just like we do with police. But it isn't true that policing is the best institution to address these conflicts, or that we can't address intra-communal violence without punishment and prisons.

After the lie that everyone's idea of safety must be the same, the next most harmful belief fostered by prison culture is that people within a community should have no stake in their own protection. Many of us have spent so long outsourcing problem-solving to police and prisons who are trained only in punishment that we have lost all reconciliation skills ourselves, sacrificing a healthy connection to our community in the process. We learn to falsely think of our neighbors as disconnected individuals whose propensity to harm can be snuffed out without snuffing out anything in ourselves, and forget what it is like to struggle together to take care of the people around us.

It's true that having a stake in one's own protection demands a certain level of bravery, but I'll be the first to admit that I am not brave always. I haven't called on the police for anything in years, which has forced me to face some difficult situations I'd rather not face on my own, and I haven't always stepped up. But I have stepped up more than I thought I would, and I have seen others who have come to embrace abolition step up when someone in their neighborhood is in danger — with de escalation or crises management tactics they've studied, with a promise to defend or actual defensive actions, with a call to someone outside of the police who might be better able to — and I know it doesn't take any more bravery than any of us are capable of because we have done it before. We did not always rely on modern policing. And there have been less such difficult moments than I assumed would occur, too. In spite of what popular media portrays, my community is not full of mindless monsters who would run rampant killing and assaulting one another if there were no untrained, state-sanctioned white supremacists to keep us in check.

So, who will protect us without police? We will. I've seen it. Outside of physically stepping up in moments of crisis, we will join our local cop-watchers or community defense organizations, or other abolitionist organizations like Critical Resistance and Common Justice. If we can't join for lack of time, we will support with donations and getting out of the way when these organizations need us to.

Most importantly, we will find safety by recognizing that prison and policing is a culture that extends beyond its officers and agents. This is a culture that says all problems must be solved with punishment, including the ways we punish ourselves with shame and guilt, which has left many of us with deeper scars than anything our neighbors could ever physically do to us. It is a culture tied up with a capitalist system that exploits the poor so much so that they might use violence out of desperation and necessity even when they otherwise wouldn't.

Abolition is not just the closing of physical buildings that hold prisoners or the disbanding of police forces. It's a process of reckoning with the punitive history of which we are all part that birthed this culture. Abolition is in how we respond to being wronged by our friends, family and neighbors, and in how we respond to our own mistakes with accountability and healing. It's acknowledging our own capacity to wrong others, and being intentional about avoiding doing so.

As I've written previously, we won't ultimately be able to get rid of police without getting rid of the abusive culture that relies on them, and so there is no void police abolition leaves behind that we should spend all our time worrying will be filled with more abuse. The void is prisons, and they are already being filled with the abuse of Black people and children everywhere. By committing to police and prison abolition, the state—which teaches those of us who today commit intra-communal harms without facing accountability—is the target. And without such a state, what exactly would we need to be kept safe from?

In the true crime episode, just because the quiet person in the quiet town is harmed or killed doesn't mean they aren't safe, depending on one's perspective. This is part of the reason why, I think, white folks find so much comfort in this genre. Until abolition is here, their whiteness remains safe, regardless of what happened to the individual person being featured. Even if the police don't catch the bad guy, they might as well have. One's sense of a world where there are "good" neighborhoods and "bad" Black ones is safe, even if a single person's physical body determinedly isn't.

Only abolition truly threatens the safety of a white supremacist society; though it asks for us to give up some comforts around what we believe to be our individual safety within it, rather than finding entertainment in watching someone else be the sacrifice (and even if not on-screen, Black people are always being sacrificed). Abolition shows that a more equitable experience of safety is possible, but you must become part of creating it.

Shares