A rare constancy of the human experience is poetry. No matter how much people degrade each other in the quest for power, profit, or a false sense of security, and irrespective of how far some try to push poetry off the cliff, poets will stand at the ready, pen in hand.

The world of letters, and particularly the United States, is fortunate that for the past four decades one of those poets in Martín Espada. Operating under a grand, Whitmanesque vision of poetic possibilities, Espada pulls together the political and personal into one literary constellation, flashing lights that expose both injustice and opportunities for solidarity.

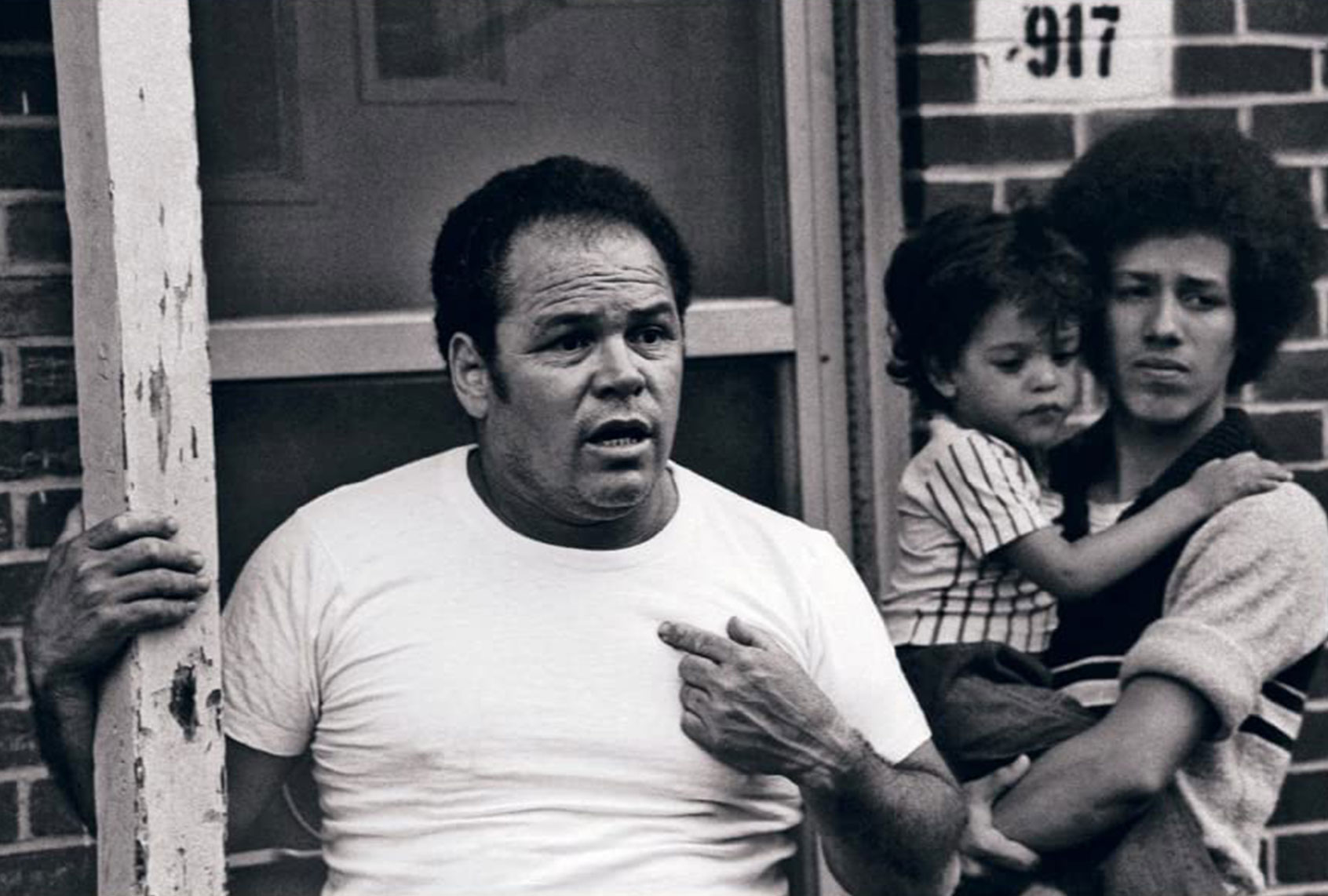

Espada was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, and followed the example of his father, a photographer and leader in the Puerto Rican civil rights movement, by striving to create a hybrid of advocacy and art. He spent his early years focusing more on the former as a tenant lawyer in Chelsea, Massachusetts, often representing non-English speaking Puerto Ricans facing eviction and suffering the exploitation of greedy landlords or an inadequate public housing system. His first book of poetry, “The Immigrant Iceboy’s Bolero,” was published in 1982. Since then, he was published more than 20 books as a poet, essayist, editor, and translator. Among many awards, he has received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and the International Latino Book Award.

His newest book, “Floaters,” features poems that deal with hate crimes, poverty, and immigration, but also love, grief, and remembrance. “Floaters” is a brilliant collection of poems that anger, delight, amuse, and shatter.

I interviewed Espada over Zoom about his work, and more broadly, poetry, politics, and activism.

You’ve said that you often have the intention to explain when you are writing a poem. Given how many of your poems deal with sociopolitical subject matter, could you walk me through how your poems begin with the specific, but then still possess the mystery and artistry that we associate with poetry?

I am a storyteller at heart. I am a narrative poet. I intend to communicate clearly, and this means there will be some attempt at explanation. This is especially true if I am telling a story that comes from a cultural, political, or historical experience outside the “mainstream” experience of many readers. That is a position to which I am accustomed. As much as I write for and about certain communities, I am always aware that other readers are going to be dealing with the unfamiliar. There are names, places, dates, history, politics, poetics, an entire perspective many will encounter for the first time. I want to communicate without sacrificing my identity or the art. I remember doing an interview with the great Nicaraguan poet-priest, Ernesto Cardenal, in 1982. I was stunned when he said, “The first duty of the poet is to write well.” This was the major poet of revolutionary Nicaragua. I remember, as a young, would-be revolutionary, being taken aback by that statement. But he was right. We have a duty to write well so we can best tell a story that may otherwise remain untold. In the service of that untold story, I pay attention to the art. As for mystery: I know where I’m going, but I don’t know how I’m getting there. I know what I want to say, but I don’t know how I’m going to say it. I don’t know what language I will use, what image I will call upon, or what metaphor will become central to the telling. I know that I want to tell this tale, reveal a hidden history or a forgotten injustice. It’s like having a map, but not having a map.

You mention making references or describing something that an audience won’t easily understand or appreciate. That seems to emphasize representation. In your new book, “Floaters,” the second section of poems – “Asking Questions of the Moon” – falls into a tradition of your poetry that gives representation – to Puerto Ricans, to the tenants who were your clients. What do you feel, in addition to first and foremost, writing well, is your responsibility as the poet attempting to represent something particular to a general audience, especially considering that it will have political implications?

Issues of representation are always complex, thorny, and difficult. Yet, consider the alternative: silence. Consider the alternative: disappearance. Consider the alternative: dehumanization. Representation comes naturally in my work as a poet, in part, because it was an essential characteristic of my work as a tenant lawyer for Su Clínica Legal in Chelsea, Massachusetts. I didn’t stop to contemplate the dilemma of representation when I was standing in front of a judge. My client was on the verge of being evicted, being made homeless, and didn’t understand a word in court. Keep in mind that the language of the law is the language of power, designed to render its victims dizzy. Imagine being doubly removed from that language of power if you don’t even speak English. It was a natural step for me to stand up in court and speak on behalf of those who could not speak for themselves. In fact, there was an ethical imperative. Can you imagine if I went into to court, and said, “Excuse me, Your Honor, I lack the authority to speak,” and sat down? I would have been disbarred. There isn’t much of a leap from what I did as a lawyer to what I do as a poet if I write a poem that documents the struggle of those without the opportunity to be heard.

Now, I don’t sit down in the morning at my computer screen to search for a headline that will provoke a storm of poetic outrage. There is usually some tangible connection with the subject of the poem. You mention one poem about my own life experience, “Asking Questions of the Moon.” I’m an adolescent playing the outfield and pondering a girl’s gently racist inquiry about my Puerto Rican identity when a baseball smacks me in the eye. Another poem in that section contemplates my father’s raucous activism in Brooklyn — and then his quiet death years later. There are poems in the first section about migrants from México and Central America, including the title poem. There is a poem about my legal work at Su Clínica and an encounter with a bigoted cab driver, called “Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge.” There is usually a tangible connection that not only allows me to follow the dictum, “Write what you know,” but gives me an emotional bridge to cross when I write about the subject.

You describe the law as the “language of power.” The poet Susanna Childress in very creative and clever ways talks about the “utility of poetry.” If law is the language or power, what is the utility of poetry?

I can tell you that the common ground is precision. Whether I am speaking the language of law or the language of poetry, there is an obligation to be precise. One word out of place, and everything may collapse. That can happen in a will or contract or a poem. As far as the utility of poetry goes: people find poetry useful all the time. We, as a society, crave meaning. In the absence of words that matter, we hunger for words that matter. We are bombarded with euphemisms, whether these euphemisms are political, commercial, or legal. We endure a barrage of words that do not mean what they supposedly mean. Poetry makes an appearance in places and moments where people crave meaning deeply. At one point, I did six memorial services in 12 months. People, in that moment, seek a way to make sense of something senseless: death. They crave meaning. Thus, they call upon poets. The same is true of weddings. I’ve done my share of weddings. That is the other end of the spectrum, a celebration, but, again, the participants crave meaning. Poetry fills that longing.

We live in an age when, ironically, we’re buried in words. We are subject to more words and images than ever, yet they come at such a high rate of speed. We see these words and images scrolling past us, only to see those words and images pushed aside to make room for the next flurry of words and images. What poetry enables us to do is to savor, to taste the words that will sustain us, in contrast with that sense of the meaningless that confronts us every day.

When I spoke to Rita Dove, she said that poetry “deals with the unremarked upon.” Your reference to death reminds me of that idea. There are several poems in “Floaters” that deal with some measure of the unremarked upon – whether it is racism, something historical – and you bring it to bear in your poetry. Is casting light upon the unremarked upon also part of the utility of the poet?

Absolutely. Often, what I intend to do when I deal with “the unremarked upon” is to humanize the dehumanized. For example, we see statistics about what’s going on right now at the southern border, numbers and more numbers. These abstractions don’t move us as they should. They don’t connect us as human beings with other human beings. If I can deal with “the unremarked upon” by presenting the faces or voices of one migrant family, that means humanizing the dehumanized. Then again, sometimes I deal with the remarked upon to accomplish the same ends. Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos were two Salvadoran migrants, father and daughter, who drowned crossing the Río Grande on June 23, 2019. A photograph of their bodies went viral. Óscar and Valeria, as they came to be known, were remarked upon. There was outrage, grief —and trutherism. An anonymous post in the “I’m 10-15” Border Patrol Facebook group charged that the photograph had been faked. The same post referred to the drowned migrants as “floaters,” a term used by certain members of the Border Patrol to describe those who drown crossing over. The title poem of my book, “Floaters,” responds to the viral photograph of Óscar and Valeria, to their death by drowning, to the charges of fakery, to the use of the slur “floaters” itself. I wrote the poem to deal with the remarked upon.

Now, almost two years later, the same poem deals with “the unremarked upon.” We see something, register horror — and forget. On the first anniversary of the drowning, I wanted to post that poem on social media, and connect it with a story in the media that would mark the anniversary. There was nothing. I noticed, as time passed and I would read that poem in public, that people were already forgetting. It is a given that what we are talking about today we may not be talking about tomorrow, and almost certainly not talking about a year from now. When I write a poem, it may appear that I am commenting journalistically on the events of the day. However, what begins as journalism soon becomes history and then becomes oblivion. This is how I remember. This is how I observe the unobserved. To come full circle, there are migrants dying right now on the border, be it river or desert. We just aren’t saying their names.

You’re reminding me of the connection that always exists, as Albert Camus wrote, between rebellion and love. The singer/songwriter, John Condron, often says, “Sometimes the best protest song is a love song.” The last section of poems in “Floaters” are homage poems to people you knew, you loved. There is no contradiction or disharmony between those poems and the earlier poems in the book that are directly political. Is the connective tissue memory?

You could say that the connective tissue is memory. You could also say that the connective tissue is forgetting. I don’t want people to forget. Maybe it’s gesture of futility. It’s not as if I can alert the entire world to the existence of people I want the world to remember. You refer to love. At the risk of coming off “sentimental,” which is considered a great sin among contemporary poets, I’d say this is a book grounded in such passions. I am best known as a political poet. You see the political poems in the first section of the book, dealing with immigrants and racism. There is a middle section of love poems dedicated to my wife, Lauren Marie Schmidt, a poet in her own right, as well as a novelist and high school teacher. There’s even a wedding sonnet in there. There are persona poems that are absolutely ridiculous. I have a poem in the voice of a Galapagos tortoise by the name of Lonesome George. From these poems of love, it’s a logical transition into the poems of homage in the last section. Most of these are elegies, a form I know well, since so many I’ve loved have died, since I’ve been called upon so often to speak at memorials, including the memorial for my father, Frank Espada. He makes an appearance at the end of the book in the poem, “Letter to My Father.” This is not only a poem for him, but for the island of Puerto Rico — and his hometown of Utuado in the mountains — in the aftermath of Hurricane María and Trump’s disgraceful neglect. There is a poem for Luis Garden Acosta, friend and mentor, a brilliant organizer and the co-founder of El Puente, “The Bridge,” a multi-service community center in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. He died a couple of years ago. This was my way of remembering him, but also telling a good story.

The elegy is not only a lament. The idea is to recall the vision, the blood and heartbeat that energized that human being. Only in the last stanza of the poem for Luis do I even mention his death. What I want people to take away is Luis in resplendent life. In an elegy, for me, death is necessary but not sufficient. What is the life force that made the person indelible?

You have one poem, “I Now Pronounce You Dead,” that deals directly with capital punishment, but also the effect of memory, which is so often haunting.

Of course, nearly everything we do in our society, we measure in dollars and cents, according to profit and loss. Poetry is an art form that usually refuses to be so measured. I write poetry not for the sake of transaction, but for communion. When I read an elegy in public, invariably someone will approach me and say, “Yes, I lost someone too.” The poem forms a bridge where we cross back and forth to one another. Once, in Boston, I read a series of elegies I wrote about my father, who died in 2014. A young woman came up to me and said, “I am glad you read those poems about your father. I lost my father too.” I said, “I’m sorry. When?” She said, “Wednesday.”

You use the word, “haunting.” We’re all haunted. When Hurricane María struck Puerto Rico, the only person I wanted to talk to was my dead father, or, more specifically, his ashes in a box on my bookshelf. In “Letter to My Father,” I call upon him to rise against Trump. That’s what it means to be haunted. In fact, there is a poem in my previous book, “Vivas to Those who Have Failed,” to my father, called, “Haunt Me.” I’m inviting him in. Most people want to keep the ghosts at arm’s length. I invite them in. The dead have as much to say to us as the living do.

Returning to the idea of “life force,” in your poem, “Ode to the Soccer Ball Sailing Over a Barbed-Wire Fence,” you write about teenagers playing soccer in an immigrant detention facility, and you have a beautiful imagining of where the soccer ball might travel – how it might not only emancipate them, but serve as a mechanism of justice in the world. Imagination is obviously essential to poetry, but how important is it to politics? It seems so much of our politics suffers under a deficit of imagination.

This is why most people find political discourse so damned dull. It so often centers around policies and the partisan. The imagination is absolutely critical to political activism, illuminating the vision of a world that does not yet exist. Vision is hope, and hope is fuel for the activist. What we imagine now might become concrete reality in this lifetime or the next. There are times when we wait decades or centuries for change, and then suddenly (or so it appears), there is change. We must be able to envision a world that isn’t here yet. Those who do so will be accused of utopianism. Guilty as charged. This reminds me of Eduardo Galeano’s “Window on Utopia.” Galeano writes: “Utopia is on the horizon. I move two steps closer; it moves two steps away. I walk ten steps, and the horizon runs ten steps further away. As much as I walk, I’ll never reach it. What good is utopia? That’s what: it’s good for walking.” Even if we don’t get where we want to go, the vision moves us in the direction of justice, and ultimately makes for a more just society.

Back to your question: Poetry invigorates the imagination. When they bring me to speak at a demonstration, a rally, a community center, an urban high school, an ELL (or English Language Learners) program, they are bringing me there to invigorate the imagination. They are bringing me to raise hell. I gladly accept that responsibility.

Do you believe that American culture’s fine arts, our poets have become too antiseptic and detached from the processes and activities you are referencing? Do you believe that our poets are not sufficiently in the streets?

Poets often accept their own marginality. We live in a mercantile culture, and there is no price tag on a poem. Poetry is famously unprofitable; therefore, poets accept this sense of being marginalized. Poets engage in self-mockery because we internalize this idea of our own irrelevance. It is easier to confine ourselves to circles of the academy or the intelligentsia. I believe poets are better than that. We are much more capable than that.

I can’t speak for all poets. As Robert Creeley put it, “Thankfully, a plurality of poetries exists.” Some poets write poems that will never go beyond those circles because those poems are not designed to do anything else. But for those of us who are poets and participants, poets and activists, poets and citizens, it is incumbent upon us to get out there. We must face that challenge of transcending barriers. I have read everyplace you can imagine. My first reading happened at the bar where I was the bouncer. I once did a reading at El Matador Tortilla Factory in Grand Rapids, Michigan. I once did a reading for young amateur boxers, mostly Puerto Rican, at the Windham Boxing Club in Willimantic, Connecticut. Every year I do readings at The Care Center in Holyoke, Massachusetts, a program for adolescent mothers, mostly Puerto Rican, who have dropped out of the public school system. Those community programs bring me back where I belong. Some people may think of these as non-traditional audiences. I think they are the most traditional of all because they go back to the idea of poetry as an oral and communal art form, which it was in the ancient world and continues to be in the present.

Sherman Alexie once said that if you want to help people, write poems about them, and sing songs for them. Do you think that’s true?

It requires a leap of faith, but political poetry is, paradoxically, a matter of faith, just as political activism is a matter of faith. The fact is that, when I write a poem or read a poem aloud, I have no idea what will happen because of that poem. You cannot quantify the impact of a poem. You cannot label it or box it, weigh it or measure it. I put the poem in the world, and it takes wing.

I will cite a professor of mine from the University of Wisconsin in Madison where I got my Bachelor’s Degree in History. His name was Herbert Hill. Hill was the National Labor Director of the NAACP. He was one of those responsible for Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, dealing with discrimination in employment. He would say to us, “Ideas have consequences.” Simply, yet elegantly expressed.

I don’t know what consequences my ideas in poetic form will have, but I do believe in the truth that Herbert Hill expressed: Ideas have consequences.