The trend of Americans exiting the pews, never to return, has been steady for some years now and shows no signs of slowing down. According to a new Gallup poll released this week, only 47% of Americans polled in 2020 belong to a house of worship, which is the first time that number has fallen below half of the country since they started polling Americans on this question.

But what's really interesting is that the collapse in church membership has happened mostly over the past two decades. Since Gallup started recording these numbers decades ago, church membership rates were relatively steady, with only the smallest decline over the decades. In 1937, 73% of Americans belong to a church. In 1975, it was 71%. In 1999, it was 70%. But since then, the church membership rate has fallen by a whopping 23 percentage points.

It is not, however, because of some great atheist revival across the land, with Americans suddenly burying themselves in the philosophical discourse about the unlikeliness of the existence of a higher power. The percentage of Americans who identify as atheist (4%) or agnostic (5%) has risen slightly, but not even close to enough to account for the number of people who claim no religious affiliation. A 2017 Gallup poll finds that 87% of Americans say they believe in God. So clearly, what we're seeing is a dramatic increase in the kinds of folks who would say something akin to, "I'm spiritual, but not big on organized religion."

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

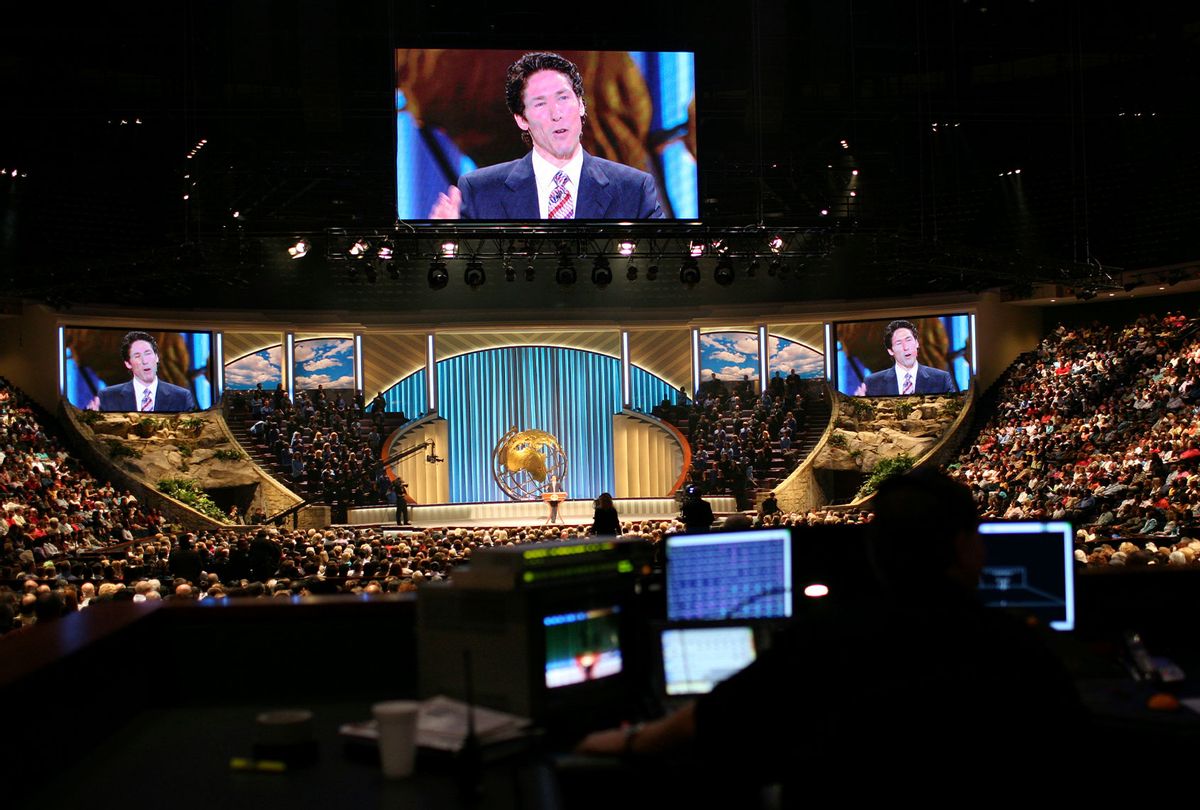

Blame the religious right. Until recently, the U.S. was largely unaffected by the increasing secularization of many European countries, but that started to change dramatically at the turn of the 21st century. And it's no mystery why. The drop in religious affiliation starts right around the time George W. Bush was elected president, publicly and dramatically associating himself with the white evangelical movement. The early Aughts saw the rise of megachurches with flashily dressed ministers who appeared more interested in money and sermonizing about people's sex lives than modeling values of charity and humility.

Not only were these religious figures and the institutions they led hyper-political, the outward mission seemed to be almost exclusively in service of oppressing others. The religious right isn't nearly as interested in feeding the hungry and sheltering the homeless as much as using religion as an all-purpose excuse to abuse women and LGBTQ people. In an age of growing wealth inequalities, with more and more Americans living hand-to-mouth, many visible religious authorities were using their power to support politicians and laws to take health care access from women and fight against marriage between same-sex couples. And then Donald Trump happened.

Trump was a thrice-married chronic adulterer who routinely exposed how ignorant he was of religion, and who reportedly — and let's face it, obviously — made fun of religious leaders behind their backs. But religious right leaders didn't care. They continually pumped Trump up like he was the second coming, showily praying over him and extorting their followers to have faith in a man who literally could not have better conformed to the prophecies of the Antichrist. It was comically over the top, how extensively Christian right leaders exposed themselves as motivated by power, not faith.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Gallup's numbers show numbers of religiously affiliated Americans taking a nosedive during the Trump years, dropping from 55% of Americans belonging to a church to 47%.

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

To be clear, the drop-off in religious affiliation is, researchers have shown, likely less about people actively quitting churches, and more about churches being unable to recruit younger followers to replace the ones who die. As Pew Research Center tweeted in 2019, "Today, there is a wide gap between older Americans (Baby Boomers and members of the Silent Generation) and Millennials in their levels of religious affiliation."

All of which makes sense. It's rare that people abandon an ideology or faith that they'e had for a long time. Once an adult actively chooses to belong to a church, it's hard to admit that you were wrong and now want to abandon the whole project. But young adults, even those who went to church with their parents, do have to make an active choice to join a church as adults. And many are going to look at hypocritical, power-hungry ministers praying over an obvious grifter like Trump and be too turned off to even consider getting involved.

In 2017, Robert P. Jones, the head of the Public Religion Research Institute and author of "White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity," spoke with Salon about how the decline in religion is concentrated largely among young people. There's "a culture clash between particularly conservative white churches and denominations and younger Americans," he explained, noting that young people were particularly critical of anti-science and homophobic rhetoric from religious leaders.

"[C]onservative white Christians have lost this argument with a broader liberal culture," he explained, including "their own kids and grandchildren."

It's a story with a moral so blunt that it could very well be a biblical fable: Christian leaders, driven by their hunger for power and cultural dominance, become so grasping and hypocritical that it backfires and they lose their cultural relevance. Not that there's any cause to pity them, since they did this to themselves. The growing skepticism of organized religion in the U.S. is a trend to celebrate. While more needs to be done to replace the sense of community that churches can often give people, it's undeniable that this decline is tied up with objectively good trends: increasing liberalism, hostility to bigotry, and support for science in the U.S. Americans are becoming better people, however slowly, and the decline in organized religious affiliation appears to be a big part of that.

Shares