The COVID-19 pandemic has lasted only slightly more than a year; the AIDS epidemic, by contrast, now spans decades. Just as AIDS has taken more than 670,000 lives in this country, scientists have long dreamed of a day when they could inoculate the population against HIV, the virus which causes the deadly disease.

It turns out that these two pandemics may be more related than anyone realized. And incredibly, some researchers believe that the same revolutionary technology which was used to create the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines could be used for an HIV vaccine.

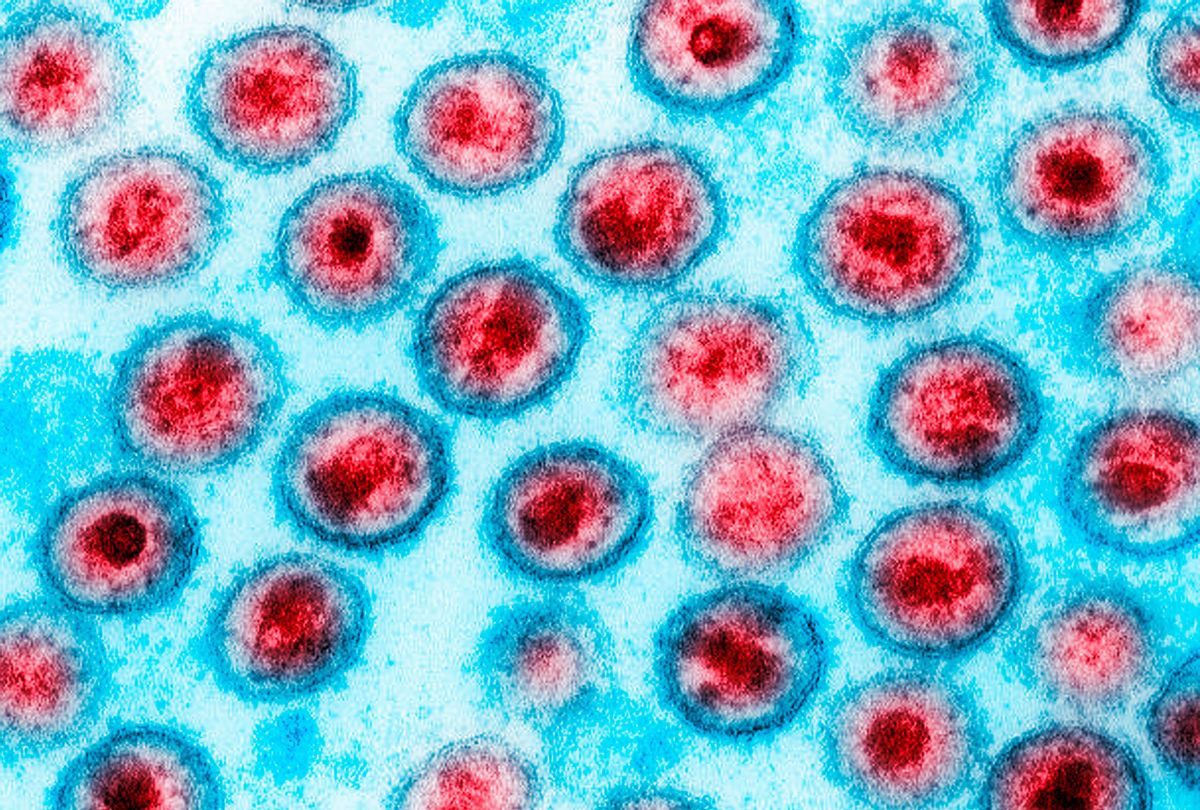

A vaccine developed by researchers at the nonprofit IAVI and Scripps Research in San Diego had a 97% success rate at stimulating production of precursor immune cells, which experts hope could eventually produce broadly neutralizing antibodies, a rare part of the immune system which have proved effective at binding to the spike proteins on HIV. (The spike proteins are the needles that stick out from the HIV's sphere like the spines on a sea urchin.) This development could be hugely meaningful to creating an HIV vaccine.

Historically, much of the difficulty in creating an HIV vaccine stems from the fact that HIV is a retrovirus — meaning that it readily mutates to avoid being thwarted by antibodies, the proteins created by the immune system to help identify and destroy foreign threats.

Yet because the HIV virus' spike proteins generally remain the same, even among different HIV strains, a vaccine that creates more broadly neutralizing antibodies could train them to target those needles — and in the process inoculate people against HIV.

To be clear, the technology is only in its very early stages. Researchers are still in Phase I of clinical trials (this means that they are only beginning to test their technology, and on a very small group of people, with an emphasis on making sure that everything is safe). The initial test group only included 48 healthy adults, some of whom received a placebo. The enthusiasm comes from the fact that 97% of those who did not get the placebo showed early evidence that their bodies could be able to manufacture these broad antibodies.

This is where the developments that led to the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines enter the picture. Unlike conventional vaccines, which train the immune system to recognize a potential threat by injecting a patient with a weakened or dead version of the antigen (the foreign body that triggers an immune response), Pfizer and Moderna developed what are known as mRNA vaccines. These vaccines use synthetic versions of mRNA, a single-stranded RNA molecule that complements one of the DNA strands in a gene. The mRNA is then modified, depending on the antigen that scientists wish to fight, and injected that into the body. It then trains the body's cells to manufacture proteins like those found in the antigen; when the cells infected by the mRNA releases those proteins, the immune system recognizes them as threats and learns to recognize them.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

The candidate HIV vaccine studied in the Phase I clinical trials was not an mRNA vaccine. IAVI and Scripps, however, are collaborating with companies like Moderna to see if they can use the mRNA vaccine technology to develop their own product more quickly and more effectively.

"mRNA vaccines could help reduce the time it takes to develop and evaluate new HIV vaccine candidates in clinical trials," IAVI President and CEO Mark Feinberg, MD, PhD, told Salon by email. "While conventional approaches can take years to advance a promising idea in the lab into a vaccine candidate that can be tested in humans, mRNA vaccine technology can reduce that time from years to months."

At least one prominent outside organization shares IAVI's enthusiasm for mRNA vaccines. Mitchell Warren, the executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition (AVAC), wrote to Salon that mRNA vaccines are promising precisely because they were so effective in fighting SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

"It's important to note that the mRNA candidates were able to move quickly into COVID-19 vaccine trials because of years of basic science research by HIV vaccine and other researchers," Warren explained. "It, therefore, has exciting possibilities for an HIV vaccine, and it's great to see Moderna looking at how to move an mRNA HIV vaccine into clinical research."

Warren noted that there is a caveat. "One key question is whether there will be the political and financial support to move a mRNA-based HIV vaccine forward with the same speed the COVID-19 vaccines were moved forward."

Of course, a huge amount of scientific and clinical work must happen before an HIV vaccine can be a reality. Vaccine development is a painstaking process, and pharmaceutical companies have to be very careful to make sure they do not create a product that accidentally hurts people.

"The results from the IAVI G001 trial are encouraging in that they validate a promising new approach to HIV vaccine design," Feinberg told Salon. "However, much research will be needed to extend this approach so that we can achieve the goal of a broadly effective HIV vaccine. We are working with partners, including the biotechnology company Moderna, to advance research as quickly as possible."

When asked about how optimistic he is about the HIV vaccine's prospects, Feinberg wrote that "based on our recent results, and should future research to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies by vaccination continue to generate positive results, we believe that it will be possible to develop an effective HIV vaccine."

He cautioned, however, that the challenge is so complex that "we don't foresee this goal being achieved in the near future," although he is optimistic that "we have a promising approach to pursue and new tools that will enable us to accelerate and optimize HIV vaccine development efforts."

Those views were echoed by Adrian B McDermott. Ph.D., chief of the Vaccine Immunology Program at the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Institutes of Health.

"We need to temper the enthusiasm seen with the initial results with the need for carefully controlled clinical trials and the accompanying experimental evaluations, such as G002," McDermott told Salon by email. "We are at the start of a long journey of clinical experimental immunology that we hope will yield robust and long lasting antibody responses for HIV and after a long time yield a safe and effective HIV vaccine."

Warren expressed similar views.

"I remain optimistic than an HIV vaccine will eventually be proven safe and effective and be rolled out to those who need it, but it's impossible to put a time frame on that," Warren explained. "There is one HIV vaccine (the J&J one) in efficacy studies now, with results expected in 2022, and another large proof of concept study of another candidate in the field. Everything else is further back in a pipeline that has been delayed by the absolutely necessary focus on COVID-19 and by the restraints of the pandemic on clinical and laboratory research."

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly explained the role of these developments in potentially producing broadly neutralizing antibodies. The piece has been updated to reflect that.

Shares