Tyler Gillespie is a man from Florida, but he's not a Florida Man, you know? Or maybe he is. Because if your only image of the Sunshine State is punchline headlines and hurricanes, you don't know Florida at all.

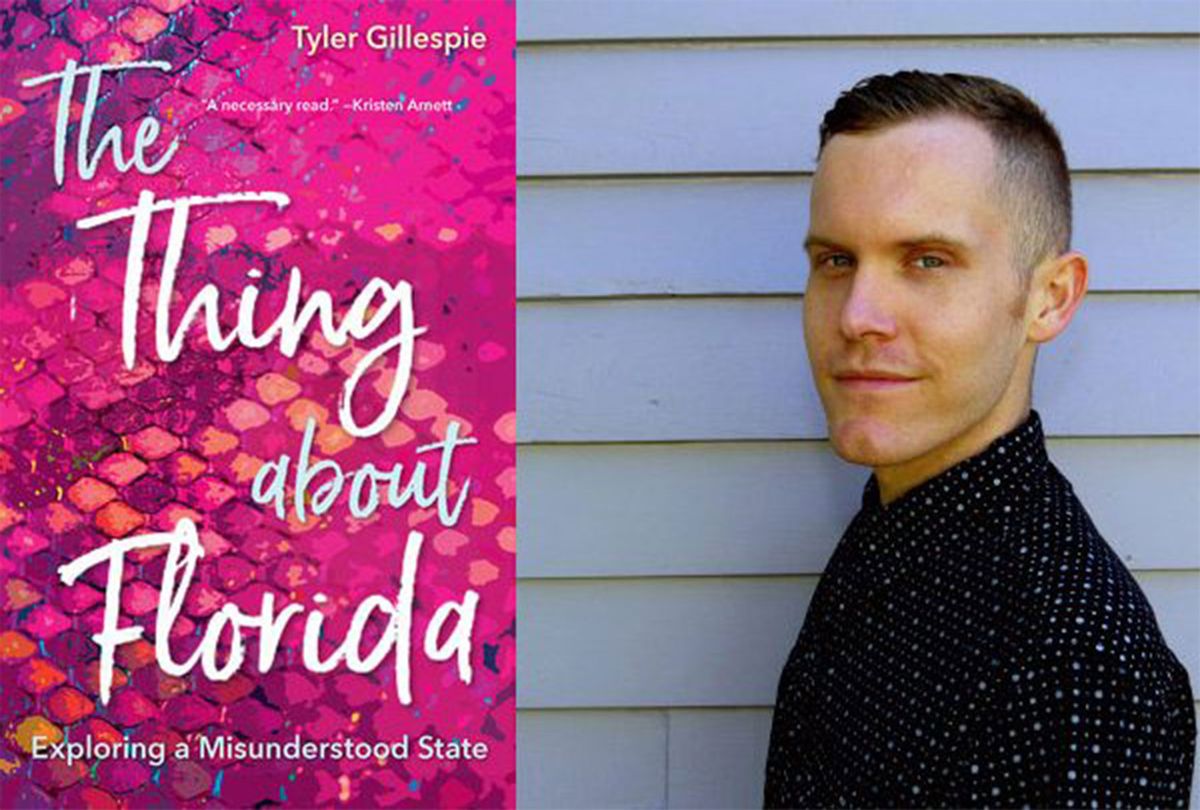

As a writer for Salon's "Young Americans" project a few years ago, Gillespie reliably sought to show a different side of his home state, one that tempered its outsized reputation with its humanity. Now, he's written a new book of essays, "The Thing About Florida," about the much-maligned and misunderstood birthplace of both Eva Mendez and Matt Gaetz. Salon spoke to him recently about the most complicated state in the union, and making peace with the place you come from.

Maybe the best place to start is where you start the book, which is the concept of the Florida Man. I'd taken it for granted the Florida Man as an idea has always been with us, but that's not the case.

I became really interested with that when I was living outside of the state. I got my MFA at the University of New Orleans. I had started to see all these headlines were going viral, and people asked me about weird Florida stuff. This was the image of these headlines, and the reputation of the state.

I never thought of Florida as very strange. I didn't necessarily love being from the state when I was younger; I don't think all teenagers love being where they're from. But then I came to connect with the state. I didn't think these things were weird until so many people were telling me they were. I needed to know more about how these headlines came to be. It seems so ubiquitous, but there are reasons why this has happened. And Florida hasn't always been the weird state.

I didn't understand that part of what makes Florida Man and Florida Woman is the relationship that law enforcement has with public records.

That's a huge part of it. We're very proud of our open records laws in this state, because we should have open records laws for our politicians and for things like that. But it does have the consequence of making it very easy for these stories to be put online. Someone can be arrested for something that they're never convicted for, that didn't necessarily happen, and there are ways to frame it so journalists can write about it without getting a libel allegation. Other states don't have those laws.

I think too, Florida has always been a place where people come for vacation, for sun, and it has that myth to it about being this fantastical place. I do think that a lot of the people who get arrested here are not necessarily from there. They may be on vacation or whatever. So it's the "Florida Man," or "Florida Woman," but it's not actually a Florida person. I think people sometimes unfortunately see Florida as a place where anything goes, and maybe they're not on their best behavior when they come visit us.

Throughout the book, you identify these concepts that are almost mythic about Florida — hurricanes, crocodiles, the Confederacy, Christianity. Then you go in there and you say, "This is what they are," and humanize and demythologize. How did you come up with what those big ideas were going to be?

I knew I had to write about alligators. You can't not write about alligators, writing about Florida. I was thinking about these concepts that people identify with Florida, like alligators or hurricanes or Florida Man, and thinking about what they actually are. Like I write, I could have been a Florida Man or I could have been a headline if things would have just shaken out a little differently. I'm always interested in the story behind the headline, the human behind the headline.

When we're on deadline for newspaper or magazine, we may not have the time to do that. What I try to do is just try to let people talk and hear what they have to say, and look for that something that I wasn't expecting. I just find that more interesting and more honest.

I loved Mary Thorn, the gator woman. Her whole story comes out of grief and tragedy and loss, and then she's got this giant bachelor alligator who can't get a girlfriend.

She's a great example of someone who, the headlines are, "Wow, she tries to dress up her alligator." Of course people are going to want to know about that, but that's where it stopped. She was going through the loss of a child and all of these things while she was raising this alligator that had been stolen and kept in the dark. People are complex. Florida's complex. What I really wanted to do is try to get those complexities without trying to make any judgment. I may not agree with something that somebody is doing, but that doesn't mean that they're not a fully realized person and that we can't learn something from their story or connect to their story in some way.

You're really candid about your own brush with Florida Manness, about your Christian education, about losing friends in the Pulse shooting. Why does that need to be part of the story?

Originally I was not in a lot of these essays. I was more interested in what other people were doing, but then there were some moments of narrative connection. I had to maybe use my own personal experience to connect some of these threads that may seem disparate. My editor and my agent were like, "We want some more of those moments."

It took me a while to figure out how to balance that. The last chapter was not in the original, final draft of the book, which I think as the most personal. I'd been working on that chapter about growing up gay person in the Southern Baptist church for years and I couldn't figure it out. Then after going through the whole drafting and everything, a reader was like, "I really feel like this should end in Orlando." I said, "I don't have an essay about Disney World, but I do have an essay about the Holy Land Experience," which is in Orlando.

So it was a process, especially for writing about recovery. Honestly, if I'm going to talk about a person's story, then it is my responsibility as a writer to at least share what is my stake in this and at least share that I have similar experiences.

With Pulse, it's really hard. I wasn't there, but people do ask me about it once they know I was living in Orlando. Bringing that up, I was able to connect to the foundation started in my friend's honor.

The book is a story about reconciling with home. That's what makes it relatable, not just as a book that's about Florida that's interesting to people who are not from Florida. We all have to come to terms with where we come from, how we were raised, who we are.

That's the thing. Florida has this reputation, but everybody's got a hometown. Everybody feels a kind of way about their home and we have to reconcile that. It's a very human thing to do. Now, I love being from Florida and I'm so glad I get to be from Florida.

We're in the midst of a real Florida Man Renaissance in the halls of our greatest power. When you look at somebody like a Matt Gaetz, is he a Florida Man? Is Donald Trump a Florida Man?

I end the book about the complexity and the redemption of some folks, but that being said, of course there are things that do not deserve to be redeemed. What I hope that is maybe we'll focus less on the viral headlines of everyday people who may be in a moment of addiction or mental health or socioeconomic circumstances or having a really stressful bad day or something, and focus more on the headlines that you're talking about, about a Matt Gaetz, about our politicians, about our water quality. The state is really important to the country in terms of many different things, We just really need to be focused more on that and less on people thinking, "Okay well, it's a wild state. Wild things go on."

Sometimes people don't take Florida seriously because of all the viral headlines, and we have very serious things going on here that affect many people that aren't just Floridian. I do hope that people will take it seriously, especially people who are residents, and vote and be engaged.

Shares