"If you ask me where I'm from, I'll lie to you," Lauren Hough writes in the first line of her debut essay collection. "I'll tell you my parents were missionaries. I'll tell you I'm from Boston. I'll tell you I'm from Texas. Those lies, people believe." The truth is she was raised all over the world in the infamous Children of God cult, a detail she kept secret for years until, with the help of the internet, she was able to connect with others like her. It turns out, as "Leaving Isn't the Hardest Thing" (Vintage Books, out now) reveals in prose that crackles with dark wit, sharp observations and stunning revelations, surviving a childhood shaped by an abusive cult with her ambition intact may have uniquely positioned Hough to see not only authoritarian religions, but America itself — its military, its criminal justice system, its bigotries, the precarious edge upon which it positions its working class — through the clearest of eyes.

Hough's book has been hotly anticipated since her HuffPost essay, "I Was A Cable Guy. I Saw The Worst Of America," went viral in 2018. In that essay and 10 others, Hough writes about navigating her way through a multitude of identities, regions, and subcultures, daring to tell the truth about America from the inside and out.

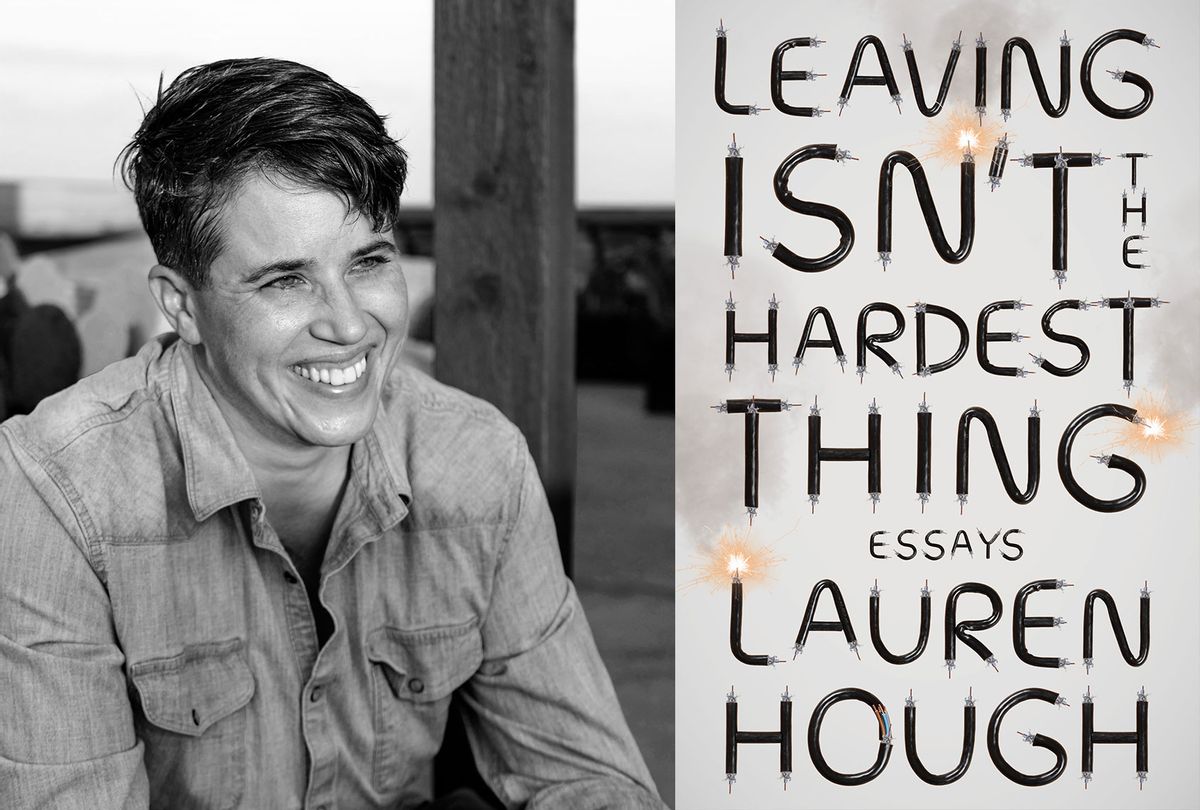

I spoke with Hough by phone last week, shortly after the delightful news broke that Cate Blanchett would be joining her in narrating the audiobook. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

One thing that I was really struck by in this book is how deeply it grapples with loneliness, particularly a specific kind of loneliness that occurs when a person is surrounded by others — first in living in group homes with the Children of God, and then with your family, and then with roommates in tiny spaces. It reaches an apex in the scenes when you're incarcerated in solitary confinement. America is supposedly this obscenely chatty, gregarious country and people, but studies also show that we're also a really lonely country. What do you think creates this paradox?

It's funny you said "chatty," because I figured out a long time ago if I talk a lot, I don't have to say anything. When you meet people, if you seem earnest — well, not earnest, I avoided that — but if you seem like an open book, and you have plenty of stories to tell, and you drop in, "Yeah, my parents were missionaries, f**king hippies, don't know what to tell you," and change the subject, people don't ask any questions. They think they know everything there is to know about you. I think we just don't connect. Nobody who's ever asked, "How are you?" in America has actually meant the question or wanted an answer. And I think that's becoming really apparent with the pandemic, because now people ask, "How are you?" and you get a world full of tragedy.

People will tell you their answer now. But are we ready to hear it?

We're not. We're just unloading on random strangers. How are you? Well, my dog died last week. Everybody has this tragic thing, and I don't think we're capable of pretending anymore and answering, "Fine, how are you?" and moving on from the conversation. We're all experiencing that loneliness right now. We're just, deeply, deeply, deeply desperate to connect.

That brings up the question of whether we're being reshaped as a people by the pandemic. Everyone is going through this big trauma but isolated from each other. As Americans, we still want to buy into this myth that this is a country where you can always start over — fresh start, clean slate, you can be whoever you want to be. Do you think that we will be able to move on for real from this? Will we just clean slate, memory-hole this last year?

I hope not. Everyone's talking about going back to normal, and normal wasn't that f**king good for a lot of us. Normal was awful. I hope we don't go back to normal. I hope we experience something together and remember it, but we're really good — as a country, as a culture — of just shoving s**t down and not thinking about it.

The term "essential worker" has become such an irony-laden term over the last year, as we apply it to the folks who stock the shelves and run the checkouts at the supermarket, or work in the warehouses that service our two-day shipping, despite the the humiliating and debilitating demands that are placed on them. And that ties in closely to one of your running threads in the book about how class and labor and gender intersect, how the American workplace's principle of your time is not your own when you're on the clock then manifests itself as therefore your body is not your own. What do you think that the mainstream media misses about America's working class, when they have such a narrow slice of it they want to focus on — namely white, conservative, straight cisgender men without college degrees?

I think the biggest problem there is the working class isn't sitting in a diner hanging out all morning [talking to journalists]. The working class is sh**ting in a Big Gulp cup in the back of their work van, because there aren't any bathrooms around. It's been infuriating to watch. People will gladly cheer for essential workers, but won't pay them.

Just f**king pay people. Nobody needs to be cheered. It's like being a veteran, being thanked for your service while they cut VA benefits. Support our troops — but not if you need anything!

America hates talking about class, right?

Yeah, we really do.

Which means hating talking about a lot of things that intersect with that, too.

We just don't like to be inconvenienced. We'll gladly support essential workers as long as it doesn't mean anything about our lives has to change at all. It's funny talking about it right now, because I just tried to commit career suicide the other night, and it backfired on me — apparently I suck at that. I picked a fight with Amazon, and told people to cancel their [book] orders. I really thought I'd get in trouble. And apparently, it's not a bad idea to make bookstores love you.

Most people have heard my name because I wrote an essay about needing to pee. When I was trying to figure out how to write it, I was talking to a couple guys I knew and I asked them for stories. Do you guys remember anything that happened? Because I don't remember 10 years. I said to my friend Andre that really, I just remember needing to pee. He was like, well, there's the essay.

I don't know that a lot of people who work in offices understand. It depends on the office, I mean, if you're working in call center, I'm talking about you. But yeah, I don't think people understand how you have to ask for a day off and beg and have a really good excuse or you just don't get one.

And we're seeing now, with sick leave, how do you stop a pandemic when people have to work sick?

And working through sickness or injury has lasting effects. I have this sentence you wrote on opiate addiction highlighted: "People are in pain, because unless you went to college, the only way you'll earn a decent living is by breaking your body or risking your life." It's so rare, almost like a Bigfoot sighting, to see this point about addiction raised in discussions about class and work in America. There's often a romanticization of "the trades" out there by people who do work in offices, who seem to want to ignore how physical that labor is, and how a lot of people can't keep doing it for their whole life.

Not at the pace that we're required to work in our Protestant work ethic. A month off in August, like the Europeans have, might have a lot of effect on how our bodies feel. But we don't have time to heal. We can't go to a doctor. How do you get better if you don't get medical care? Even if you have health insurance, you don't have time off to do it.

There's constant jokes about rednecks and their opioids. It's not "rednecks and their opioids," people are in pain. And the doctor prescribes them opioids because they have to go back to work the next day. Or their buddy gives them a few because they have to go back to work the next day, and it's really easy to get addicted. I got addicted after I had a sinus surgery. It took maybe a week of intense pain and horrific withdrawals that were real. And I don't even like opioids, I get nauseated on them, so I don't take them. But yeah, it's really easy to get addicted.

Let's talk about the word "cult." Your book is not a tell-all cult memoir. But you write about your childhood with the Children of God as the big secret you carried for much of your life. If you start listening for the word "cult" it's kind of everywhere these days. Donald Trump voters are a cult. QAnon is a cult. CrossFit is a cult. On one hand, maybe we're diluting this term. But I think your book also makes a strong case that cult-like leadership behavior shapes a lot of our mainstream institutions, too.

Yeah, I think that's what I wanted to say with that. I spent most of my life just twitching at the word "cult." But when you start talking about and thinking about what it actually was, it's not all that different from what most of us experience as Americans, or as employees of a store that want you to be loyal to the store instead of paying you [well]. We throw the word around a lot, but maybe it's appropriate. And maybe it's fine that it's diluted, because it's apt. Our groupthink, our tribalism, our gather together to follow personalities instead of policy [tendencies] in politics. It's kind of bizarre, but I thought [being in a cult] was this huge secret, and it turns out pretty much every American can relate to it.

There's aspects of it in how you write about the military. There's definitely strong parallels made to mainstream religions, as well, and evangelicalism.

That was the shocking thing, coming out of the cult and realizing none of their beliefs were really that weird.

I really thought it was just a Children of God thing: We thought the Antichrist was coming, there would be a mark of the beast. And now, there are entire Facebook groups dedicated to warning you the vaccine's going to insert the mark of the beast into you. And it's still a little baffling to me. I really thought the end of the world would be more exciting and less f**king stupid. I'm supposed to be fighting the Antichrist, and I'm just not putting a bra on and watching Netflix.

Speaking of Netflix. There was that "SNL" musical sketch a few weeks ago about women who like murder shows, and in the end, it takes that little turn when Nick Jonas comes home and is like, baby, let me introduce you to the cult show. There was a violent crime in my extended family, and I get twitchy about the idea of it popping up as a story on one of those murder comedy podcasts. So I wonder what it's like for you to see cult shows — docuseries like "Wild Wild Country" and the NXIVM exposés — out there in the pop culture discourse?

It doesn't make it fun to tell people you were in a cult when people start thinking about NXIVM. That documentary is problematic for me anyway, because you're asking people who've been out of a cult for a week to explain what happened to them. I mean, f**k, it's been 20 years, I still don't know what the f**k happened to my family. I wrote a book about it, but it's not an easy thing to explain. You can't be the expert on your own life, which is a really weird thing to say for someone who just wrote a book about my own, but — [laughs] I'm f**king selling it here —

This career suicide you keep trying to commit is not going to work.

I'm going to tank the book, goddamnit! Nobody read it. Please don't read my book. The more I tell people not to, they're just going to. We don't really follow orders really well. I do love that about Americans. [Laughs.]

I used to think we were watching the crime shows, especially as women, as homework. What situations to avoid, and what men to avoid. But we kind of already know not to get into a stranger's car. Also, now we do it as practice, to get any place you get in a stranger's Uber and drive around. I used to think we're doing this as homework, but I don't think — we're just feeding off of people's tragedies for entertainment. I don't know why we do that, except maybe our home lives are really too hard to look at. It's easier to look at something shocking and weird in someone else's life than understand why our lives are f**king miserable.

To go back to what you were saying earlier about companies that demand loyalty from their workers, maybe we're also looking for recognition in these more extreme cases?

Yeah, it might be. It also seems like more of an easy fix: Don't join a cult. Cool. Wrote that one down. If he starts branding people, you should probably leave. Those are all pretty easy fixes. But you know, we're looking at the next 20 years of our lives before we can retire going to work every day for a company that is a cult because they don't want to pay us or give us time off, in a country where we can't even get f**king health care or our college paid for. "Walk out when they start branding people," is pretty easy advice but we can't really escape our own lives.

Yeah, maybe it's supposed to make us feel a little better to think, like, we're not there yet.

America is kind of founded on Oh, at least I'm not that guy. That is what we've got.

You were joking earlier: Don't read my book, don't read my book! For writers who write memoir and essays, people read their work and they feel like they're very close to the writer. When in truth they only know what you're allowing them to know. This is a crafted work of art, and they're the reader, not a confidant. You've probably experienced the weird side of that: people feeling like they know you well enough to comment on you as if you're either a very intimate friend, or even like a character on a show that they watch. I'm curious about how you navigate that public attention now as a writer in light of what you've written about having to keep so much of your life private for so long.

Yelling "I'm a private person!" if you've just written a memoir is kind of like yelling, "I'm not crazy!" but it doesn't really jibe with the fact that I just put out a book of really personal essays. But they are kind of a snapshot. And I don't know that people understand that. We don't really understand the parasocial relationship as consumers. I understand a little more now that I'm on the other side of it. I whine a lot about not getting a book tour [because of the pandemic] because I feel like I'm getting robbed, but at the same time, I do get to avoid a whole lot of people trying to hug me. I don't think people wrote reviews of any David Sedaris book talking about how much they wanted to hug him. I don't think that happened. I don't think anyone's ever called Augusten Burroughs "brave" in a review, and I think there is a little bit of a sexist bent to it.

I put the book out. And that's what you get. We're all in therapy to figure out walls versus boundaries. And I'm trying to step away from Twitter a little bit. I mean, I'm still compulsively tweeting, God help me. But I'm trying not to put so much personal information out there. I got on there because I wanted to connect to other writers and figure out how to publish a book, but that's done now. And while I'm still trying to connect to people — we're all f**king lonely, sitting around in the pandemic, trying to talk to someone — but yeah, I don't want to be consumed, and it feels a lot like I am being consumed for entertainment.

You are a very funny writer. I think there is this perception out there, perhaps, that comedy is natural, it's innate, it's easy, if you're a funny person anyway. Not that it's a craft, a skill, that takes conscious work. You use humor very skillfully and adeptly in your essays in a way that feels like an act of writerly generosity, and it's a craft element that isn't always highlighted when we talk about essays on difficult subjects.

It is a skill level. How do you make child abuse hilarious?

How did you develop that muscle? Because you are very purposefully funny about topics which are also horrific.

Gallows humor has been around for a little while. I didn't invent it. We joke to process things.

I can get kind of emotional writing something and I want to make a point and I want to drive it home. But you have to add a little bit of levity or give people the tools to read it. Especially in the beginning, we add a few funny things to like, Hey, we're going to get through this. It's not going to be that bad. I'm not going to make you need a shower after you read this book. It's just practice. And Twitter came in handy there a lot. How to tell a joke? Follow a bunch of comics and watch the way they work, watch how they arrange a story so that it's funny, not tragic. The most tragic things can be the funniest. I just think it's the way our our emotions work. We like that release.

Who are you reading right now? What books are you excited about?

Speaking of serial murderers and podcasts, Elon Green wrote this book ["Last Call"] about a serial killer in the '90s who was killing gay men in New York. And he did it a different way, I think, than any of the podcasts. I tweeted about this other day, but really, really the worst thing I think that can happen to you besides being murdered by a serial killer, is to have someone on a podcast giggling about it. He put the victims in it first. He tells their stories. And they're treated with such tenderness. And he doesn't make them the perfect victim. It's this history of gay New York, which of course, I'm fascinated by because I was too scared to go to New York. So I like to read about it.

Your book gives a really great snapshot of a particular time in gay D.C. too, and also in the South, which is often overlooked in LGBTQ narratives. Like what it's like to try to find the one gay bar in a 100-mile radius of your rural town.

You don't think about it when you're living it. But any Gen Xer is now really horrified when it occurs to us that people are talking about the '90s like we used to talk about the '60s.

Jesus Christ. [Laughs.]

I'm sorry I just ruined your week.

I routinely feel old. But Don't Ask Don't Tell was only repealed 10 years ago. And I feel like that's something that has been memory-holed fast, like, well, that's over! In the same way that people tried to pretend that because we elected a Black man president, racism is now over! And the progress we have made feels so fragile right now. I think it's important that books like yours and Elon Green's are chronicling that time, which was not that long ago. But it is often treated like ancient history to be swept under the rug.

Yeah, we really don't like to look at our pasts. Which is the f**king problem. Because we're doing it to trans people now. There's a [North Carolina state] law that just passed where teachers have to report to parents if a kid doesn't fit the correct gender performance. And that's every tomboy. Every boy who's a little bit into art. And God help us, lesbians like to clearly pretend that trans rights have nothing to do with them. But it does. If someone is being oppressed, it really does affect all of us. And forgetting where we came from doesn't f**king help. We haven't won yet. I don't know that we're ever going to win. You do actually have to still keep fighting these things. Because yes, gay people are allowed in the military. And now finally trans people are allowed to be in the military. But they're not allowed to play high school sports?

People like to say about the generation coming up that they're not going to stand for this bigotry any longer, so its days are numbered. Is this the last gasp of institutional bigotry trying to sink its claws in before it's replaced? Or are we going to be fighting the same fights for years to come?

I mean, I thought Gen X would get rid of a lot of it because we were always watching MTV and they told us racism was bad. And we watched "The Real World," and we watched our favorite gay character die of AIDS. I thought we would make some changes. We've made a few. I have a lot of hope for the next generation that they'll make a few more. But that's a lot of weight to put on an 18-year-old.

Shares