President Joe Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan proposes awarding grants and tax credits to cities that change their “exclusionary zoning laws,” like single-family zoning laws, which restricts apartment buildings and multifamily units in areas zoned for single-family housing. Activists say the move is a start in addressing the country’s affordable housing crisis, but it could also be key to promoting racial justice and improving public health for those in lower socioeconomic brackets.

Exclusionary zoning laws refer to ordinances that have been used toe exclude certain types of land use in a city or community. For example, a law stating that only single-family homes can be built on land. Such laws have a racist history, and have contributed to the limited supply of available housing in various parts of the country.

For these reasons, and many more, organizers and experts who have studied the history of exclusionary zoning laws and the consequences that remain are cautiously optimistic as to whether such an incentive alone is enough to eliminate single-family zoning laws, and overall to create sustainable and equitable in America’s neighborhoods.

“In order to really get at the problem — I mean even if you’re not talking about building affordable housing, you’re just talking about neighborhood change — you have some really big systemic issues around the inherent and implicit bias in the under assessment and undervaluing of homes and communities of color,” said Flora Arabo, national director for state and local policy at Enterprise Community Partners. “Communities of color are chronically suffering from lower home values, and a lot of those underlying issues which are also relics of redlining and just systemic racism and housing, eventually have to be addressed.”

The Biden’s administration’s focus on exclusionary zoning laws, which have a racist history of cornering low-income families, especially families of color, to segregated neighborhoods and pricing many out of the housing market, speaks to a movement gaining momentum across the country— but it’s not necessarily favored by all Democrats. While more cities are taking a deeper look at how consequential single-family zoning laws are today, others — even those that are socially seen as “progressive” — are facing setbacks in part due to NIMBY (an acronym for the phrase “not in my back yard) attitudes. The phrase, which is believed to have first appeared in the 1970s, is used to describe people who don’t want construction that is perceived to be “undesirable” — like a jail or homeless shelter — in their neighborhood.

“Some of these [NIMBY] attitudes and [single-family zoning] policies don’t skew right or left on the political spectrum,” said Dr. Tony Iton, a lecturer of health policy and a senior vice president at The California Endowment. Iton said that even in the progressive Bay Area, there are many instances of “aggressive NIMBY-ism and thinly veiled racism, people resisting things like affordable housing — even for seniors, housing for people with mental illness, homelessness or family homelessness.”

Earlier this year, the city of Berkeley in California vowed to end single-family zoning by 2022 by passing a resolution. The attention around the effects of single-family zoning laws came after a study from the University of California–Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute ranked Berkeley the eighth-highest in neighborhood segregation among nearly 100 Bay Area municipalities. The study’s co-authors said zoning laws had an “unequivocal” effect.

In Sacramento California, where 70 percent of residential neighborhoods are zoned for single-family homes (duplexes are allowed on corner lots), politicians are in the process of approving a proposal that would eliminate single-family zoning laws in the city. Minneapolis became the first city in the country to ban single-family zoning laws, which went into effect in 2020, but it also faced resistance from taxpayers.

But it’s not just a housing issue. Iton argues that exclusionary zoning laws are also a public health threat. Iton started studying how zoning laws have “profound health effects” on the people who have been forced to live in specific neighborhoods because of exclusionary zoning laws. He found in Oakland, California, a person’s zip code affects their life expectancy.

“We analyzed about 400,000 death certificates over about 50 years, and we saw these patterns that were very clear that showed up to 22 years of a life expectancy difference between certain neighborhoods in Oakland between the Oakland Hills,” Iton said. “We’ve subsequently replicated that analysis in multiple different cities around the country working with health departments around the country, something like 15 different cities, and we saw the same patterns in places like Chicago and Cleveland.”

Iton said that the neighborhoods with lowered life expectancies often lacked single-family zoning laws, and the other necessary infrastructure that contributes to a healthy neighborhood.

“And you see the absence of all kinds of other infrastructure, like parks, grocery stores, in some cases, sidewalks, and bike lanes, healthy water and issues like that compromised in some of these places” Iton said. “So it wasn’t just, you know the geography of where you live, it was also the investments that the cities and counties had made in those places over time in infrastructure.”

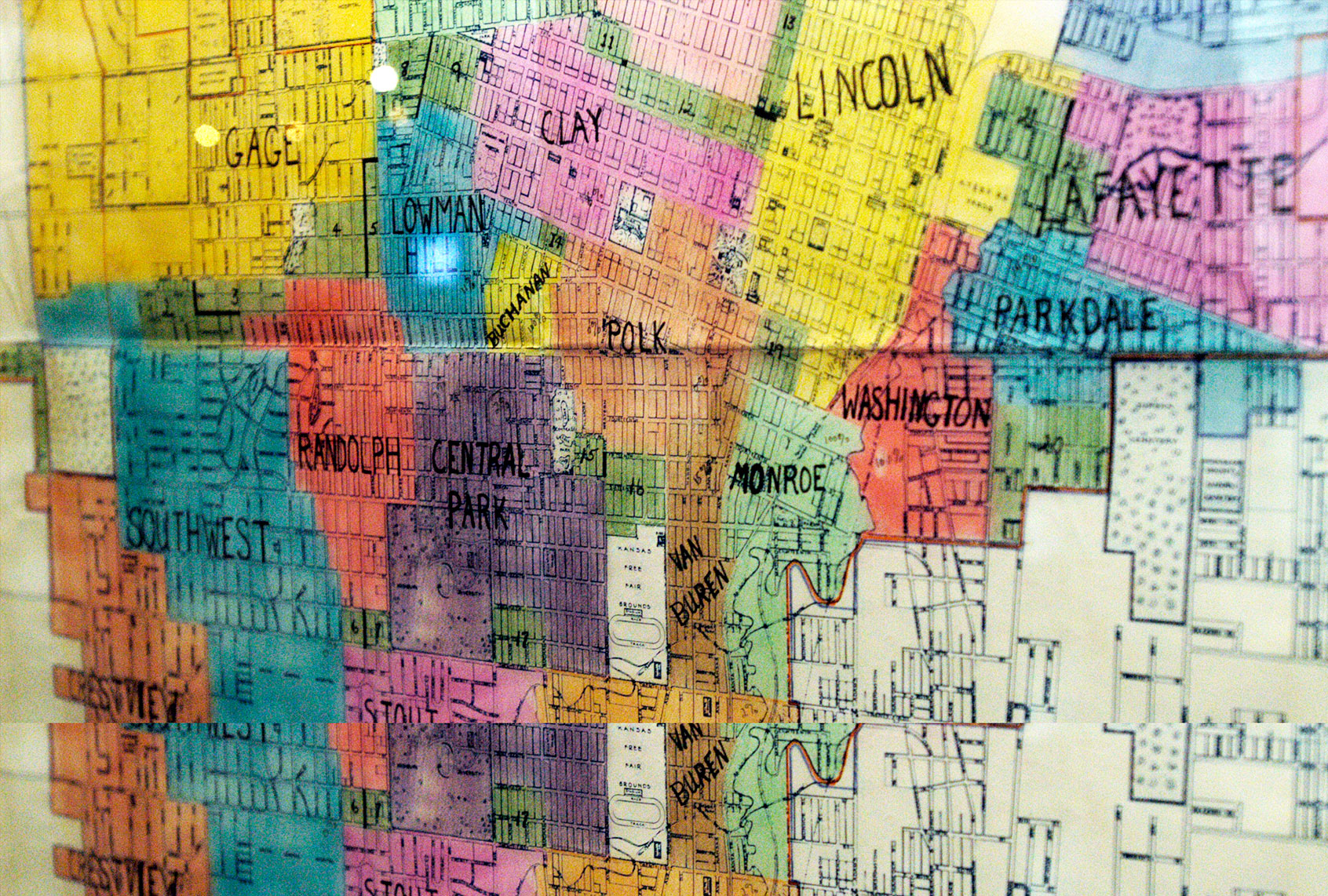

When Iton dug deeper, he found that in many of these cities the zoning laws replicated previous redlining laws.

“Redlining was a federally government sanctioned practice to essentially grade the quality of investment that should be offered in various different parts of communities,” Iton explained. “And those places that had the lowest life expectancy had been redlined, historically.”

Indeed, single-family zoning laws are the “natural descendant” of redlining. Iton said eliminating single-family zoning would be a “major tool” in dismantling the “Americanized apartheid” that “was designed to separate people by race and, and to some extent, by class.”

“I think we’re going to need more tools than just that tool, quite frankly,” Iton said.