You probably haven't heard of Saul Sanchez. But you know his story. It's been told millions of times in the history of the United States, with endless variations on the same themes. When Saul was a young, married father living in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, his daughter Patty became seriously ill. Even though Saul had a good job managing pharmacies, he couldn't pay for her medical treatment. So he came to the U.S. in the early 1970s, in hopes of saving Patty's life. He traded in a necktie for a shovel, working a series of landscaping jobs. He and his wife raised their six children in Colorado. And eventually, Saul found another job, in one of America's toughest industries: meatpacking.

Industrial meat processing has never been glamorous work. It's physically demanding, repetitive and dangerous. Workers stand side-by-side for long hours at fast-moving belts, wielding sharp knives and saws, performing the same motions over and over — all to put food on our tables.

That's the work Saul was doing when, at 78 years old, he caught COVID-19 last March. On April 7, he died in the hospital. He had kept working at the meatpacking plant until he became too sick to continue. Like so many victims of the pandemic, his wife and children couldn't be at his side when he took his last breath. But Patty was there — because she's now a nurse, working in the same hospital.

As a meatpacking worker, Saul was at an elevated risk of contracting COVID-19. When the pandemic exploded in the United States last year, infections almost immediately skyrocketed within meatpacking plants. State by state, month by month, the number of meatpacking workers sick and dying of COVID-19 stacked up with the same brutal efficiency as the lines they work on. At least 570 workers sick from one plant in North Carolina. At least 929 sick from one plant in South Dakota. At least 522 sick from one plant in Iowa. All told, more than 58,000 meatpacking workers have contracted COVID-19, and nearly 300 have died.

This suffering was avoidable. The Trump administration could have stepped in to protect workers — for instance, by issuing emergency safety rules under the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) to enforce distancing and physical barriers between workers, and to require companies to provide personal protective equipment and universal COVID-19 testing, as the United Food and Commercial Workers union called for repeatedly. Not only did the administration fail to take those steps, it did the opposite, issuing emergency rules that actually allowed companies to speed up production lines — making an already dangerous industry even more so.

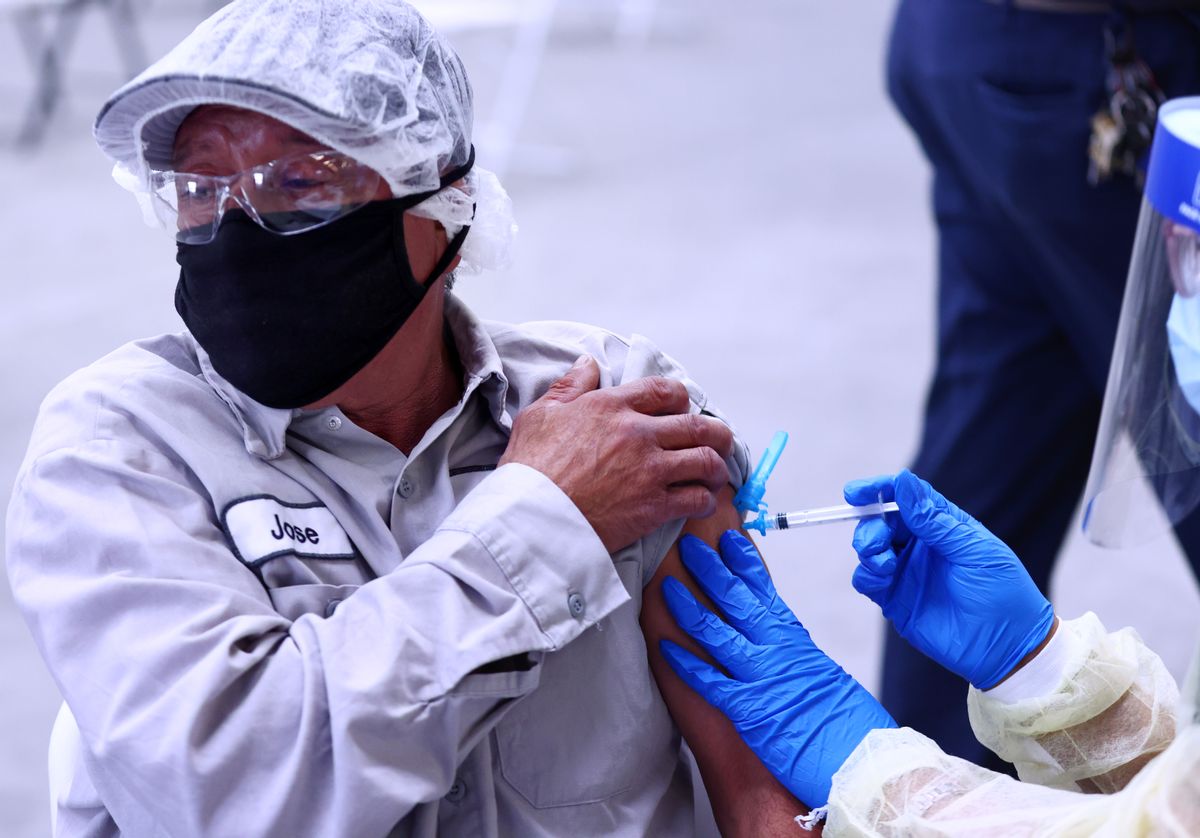

The Biden administration finally issued a COVID-19 emergency OSHA standard for meatpacking facilities in February, and many states have prioritized food processing workers for vaccines. But even without a pandemic, meatpacking has long been an industry rife with worker abuses. Injury rates in meatpacking have been stubbornly higher than in other industrial manufacturing jobs for years. Earlier this year, a liquid nitrogen leak at a poultry plant in Georgia that had been repeatedly fined by OSHA killed six people, two of whom were immigrants from Mexico.

Immigrants just like Saul. Immigrants who are caught in a double bind — first, by an antiquated immigration system that keeps workers marginalized and exploited, and again by woefully inadequate enforcement of our nation's bedrock labor laws.

And when immigrant workers are hurt, all workers suffer.

* * *

For decades, the political debate around immigration in the United States has been primarily focused on the question of legal status — who gets it, when and how.

The dominant Trump wing that has taken over the Republican Party wants to slam the door on virtually all immigrants, and especially to immigrants of color, restricting people's ability to migrate to the U.S. based on their faith, race and wealth.

Meanwhile, pro-immigrant reformers — like me — have focused overwhelmingly on advocating for pathways to citizenship for the approximately 11 million undocumented community members who consider the U.S. their home. The place where they are raising their families, starting small businesses, working to fulfill their potential and achieve a better future for themselves and their loved ones — all the while contributing to our economy and society.

We know that immigrants are essential to who we are as a nation. But what Saul's story shows — what the stories of the workers who have died of COVID, and the six killed in Georgia, and the countless others who have been injured or maimed or killed on the job over the decades all show — is that a path to citizenship for immigrant workers is necessary, but not nearly sufficient.

Citizenship hasn't kept Black and brown men and women safe from police brutality. It hasn't resulted in equal pay for women, or for men of color. It hasn't stopped worker pay from stagnating, or benefits from being slashed. It hasn't protected women — including famous and powerful women — from being sexually harassed or assaulted on the job. It hasn't stopped systematic efforts to undermine employment protections, from the rise of gig-work platforms that insist workers are independent contractors to diminishing budgets for enforcement of state and federal labor laws.

That's why we must strive for full citizenship for all. A citizenship where people are free from harassment and violence, in our communities and in our workplaces. A citizenship that values every person's contributions — women as well as men and trans people, Black and Asian American and Pacific Islanders as well as Latinx and white, immigrant as well as native-born. And to get there, we need a new paradigm of worker justice — and the policies to realize it.

These economic trends, and the profound harm they cause to American workers, aren't inevitable. They are the result of deliberate policy choices that cut across industries, and are made plain, again, in meatpacking. You might have learned about Upton Sinclair's "The Jungle" in high school history class, depicting the brutal and often unsanitary conditions in Chicago's meatpacking facilities. In the years that followed, a substantial unionization push for both Black and white workers led to nearly 90 percent of workers in the meatpacking industry being covered by collective bargaining agreements, with guaranteed wages and overtime. A 1952 Department of Labor study of 50 such agreements in the industry found "virtually every worker in the study" received three weeks of paid vacation, as well as paid sick days. For a while, "The Jungle" was tamed, and meatpacking jobs started becoming middle-class jobs.

But this progress didn't last. It was deliberately picked apart over several decades. First, companies began moving meatpacking plants into rural areas, where unions didn't have as much support. By being the biggest fish in a smaller pond, management could more easily frighten workers and elected officials with the specter of layoffs. States began passing laws that undercut unions' ability to organize workers. Then the industrial meat manufacturers began consolidating, squeezing out competition and gaining even more power to keep down wages and cut corners on worker safety — because workers had fewer places to look for jobs.

Yet who do the corporations and the politicians and conservative commentators blame for the sorry state of affairs for America's workers? Immigrants. If only immigrants weren't taking all the jobs, they say, then everything would be different. If only immigrants weren't undercutting American workers, of course wages would be higher.

They have designed and conducted a misinformation campaign that pins the blame on people like Saul for an economic system they themselves created — as though a 78-year-old working an intensely physical, low-paying job is somehow behind four decades of wage stagnation, skyrocketing income inequality and a systematic effort to undercut worker protections. They use race and immigration status to divide workers against each other, all to support a predatory form of capitalism that makes the rich richer and leaves the rest of us behind.

It's time for Americans to stop buying these lies. It's time for workers across race, national origin, class and immigration status to join together to fight for our future — the same way we did when we won better wages, safer workplaces, and civil rights advances in the 20th century.

Just as our society is judged by how we treat the least among us, we must judge our employment laws by how well they protect our most vulnerable workers. And by that measure, all workers are losing out in today's economy — no matter their industry, income, race, gender, national origin or immigration status.

We urgently need policy change at the federal, state and local levels to put real teeth back into America's labor laws. We need more funding for enforcement, increased penalties on employers who violate the law and measures to restore and strengthen the right of all workers to organize and collectively bargain. We need policies that will empower and encourage undocumented workers and guest workers to fight back against abusive employers — because allowing bad employers to go unchecked undermines workplace protections for all workers, citizens and non-citizens alike, and gives those abusive employers an unfair economic advantage over the majority of companies that do play by the books.

If we hope to actually accomplish any of this, those of us working for change need to stop talking about immigrant workers from a defensive posture. Organizers, researchers, activists and progressive politicians should speak not only to how immigration reform will help immigrants, but how it will also help all workers; not only to how labor reforms will help unions, but also how all Americans — including aspiring citizens — will benefit.

The facts are on our side — and so, too, is the more powerful American story. As the late Sen. Paul Wellstone used to say, "We all do better when we all do better."

* * *

America's economy is built on labor exploitation. At first, that labor was forced, and highly racialized — the work of enslaved people of African and Indigenous descent. After the Civil War, that labor became exploitative in more subtle ways — the economy of sharecroppers and Jim Crow, of factory workers at the mercy of their bosses, of seasonal migrants and, indeed, of immigrants. For most of the last two centuries, immigration and labor in the United States have been entwined, as in a dance — two steps forward, one step back.

Corporations brought in Chinese laborers to build railroads to connect the West — and once that work was done, lawmakers passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Southern and Eastern European immigrants came in droves to work in factories and sweatshops, powering the Second Industrial Revolution — and then lawmakers passed strict quotas capping annual immigration by nationality.

When tens of thousands of workers rallied in Haymarket Square in Chicago in support of an eight-hour workday and a bombing killed several policemen, it was German immigrants who were wrongfully accused and ultimately put to death. Chicago police cracked down on labor organizers, destroying their meeting places and arresting and beating people in the streets.

The international labor community commemorates the Haymarket Affair by celebrating May Day, May 1. Since 2006, immigrant workers have adopted this day to demonstrate that immigrants' rights are workers' rights and calling for just and humane immigration reforms.

Most Americans don't realize that until 1986 — when the last major U.S. immigration reform law was signed by Ronald Reagan — it was perfectly legal for businesses in the United States to knowingly employ undocumented workers. In enacting the Immigration Reform and Control Act, Congress allowed nearly three million undocumented workers to obtain legal status — and, in exchange, began policing civil immigration violations like criminal activities, though increased detention and deportation, along with militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. The 1986 law also created the I-9 system, which requires that employers verify the workers they hire are eligible to work in the U.S.

In theory, I-9 — and the electronic "E-Verify" update that some policymakers have pushed in recent years — is a system of "employer sanctions." But instead, employers factor in I-9 fines as a cost of doing business, and for the last 35 years, it's often only employees themselves who have been sanctioned. That's because the 1986 law gives abusive employers a powerful tool to use against undocumented workers.

In non-unionized workplaces, any employee who comes forward to report abuse — whether it's unpaid overtime, a dangerous piece of equipment, sexual harassment or even rape — is taking a risk. The law is supposed to protect those workers from retaliation. But in practice, unscrupulous employers can and frequently do punish workers who report labor law violations: by reassigning them to different tasks, giving them less-desirable shifts, cutting their hours, or even escalating the harassment and abuse that they reported in the first place. Workers' rights to organize and bargain collectively are similarly protected by federal law, but in more than 40 percent of union organizing drives in recent years, employers were charged with violating those laws — including illegally firing workers in one of every five such cases.

On paper, the laws that protect workers in the United States from employer abuse don't discriminate based on immigration status. That's because no matter who you are, your employer has more power than you do as a worker. Even in 1986, Congress understood it was necessary to ensure that undocumented workers were considered covered "employees" under labor and employment laws, so employers did not have an incentive to hire them over U.S.-born workers and make conditions worse for all workers. But undocumented workers face all the same risks that U.S. citizens do, plus the possibility of exile, should their employer decide to report them to immigration authorities for speaking up.

That's obviously bad for undocumented workers, who can be forced to endure brutal conditions to make ends meet. But it's also bad for U.S. citizen workers and immigrants with work authorizations, many of whom work side-by-side with undocumented workers.

Workplace complaints rely on corroboration. If one worker's rights are being violated, it's likely that other workers' rights are being violated, too. But if undocumented workers have reason to fear their employers will report them to immigration authorities, they're less likely to feel safe backing up an employment law complaint filed by a worker with legal status. During union drives, undocumented workers face a heightened risk of being retaliated against, including being fired or reported to immigration authorities. So it's no surprise that workplace abuses are so common in places that employ undocumented workers. One study found that of 184 workplaces in New York City investigated for immigration violations, 102 were also being investigated separately for employment-law violations.

One of the first plaintiffs I ever represented taught me how employers can game the I-9 system to retaliate against workers. Silvia Contreras was a bilingual secretary at a California company that sold trucking insurance. After her employer failed to pay her — or paid her with checks that bounced — for many months, she finally quit her job and courageously filed a claim with the California Labor Commissioner. Her employer retaliated by calling the Social Security office to inquire about the Social Security number Silvia had used on her paperwork — and then called the immigration authorities.

When I learned that Silvia spent a week in detention simply for trying to recover the wages she was owed, we filed a federal lawsuit against her employer for retaliation under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The thing is, the FLSA doesn't discriminate based on your immigration status. If you work in this country, your employer has to pay you. If your job qualifies for overtime, same thing. Again, the I-9 system is supposed to punish employers who break the law, not the workers. Ultimately, the court found in Silvia's favor, and she was awarded $40,000 in damages. But she never saw a dime of that — because her former employers declared bankruptcy, in part to get out of paying her what she was owed.

Silvia's courage did, however, establish a groundbreaking legal precedent, clarifying that undocumented workers are protected from retaliation under the FLSA. Her case has been used since then to benefit countless other workers who have suffered similar exploitation and retaliation at the hands of bad-actor employers who use the I-9 system to try to circumvent labor laws and depress working conditions for all.

* * *

While bad employers and their political allies manipulate our nation's labor laws to get away with exploiting immigrant workers, the truth is that our country wouldn't function without them. Undocumented immigrants are part of our families and communities. They are our neighbors, classmates and students. And they are workers fully integrated into the U.S. economy. Of about 7 million undocumented people in the U.S. workforce, three in every four are working in industries deemed "essential" during the COVID-19 pandemic, including some 225,000 health care workers and 389,000 farmworkers and food processors. Millions more are employed in food service, delivery, warehouses and manufacturing. Undocumented workers in "essential" industries pay $47.6 billion in federal taxes and $25.5 billion in state and local taxes each year, and hold $195 billion in spending power — which means money they put back into the economy by paying for goods and services in local communities.

A path to citizenship for undocumented workers would further unlock their economic potential — allowing them to leave abusive employers, bargain for higher wages and better working conditions, organize and join unions — and raise the floor on standards for all workers. The 700,000 people who voluntarily applied for temporary relief from deportation through the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy — commonly known as Dreamers — paid $4 billion in taxes in 2017. The libertarian Cato Institute estimated that, had the Trump administration succeeded in ending DACA, it would have cost the U.S. $60 billion in lost revenue over 10 years — to say nothing of lost opportunity.

That's because for virtually any economic challenge facing the U.S. today, immigrants are a key part of the solution. If you're concerned about Amazon destroying the mom-and-pop economy, it's worth noting that more than 1 in 5 small businesses in the U.S. are immigrant-owned. If you're fretting about the U.S. falling behind on innovation and entrepreneurship, you should take heart in the fact that 30 percent of new entrepreneurs in the U.S. in 2017 were immigrants. If the pandemic served as a wake-up call about shortages of health care and home care workers, then you should celebrate that more than one in four doctors in the U.S. were born in another country, and about one million home care workers are immigrants.

And if you're bemoaning stagnant wages and poor working conditions, you shouldn't blame immigrants this May Day — you should harness their power, and call on Congress to finally recognize them under the law.

* * *

That's what the Fight for $15 movement has done. Growing out of a 2012 walk-out of about 200 fast-food workers in Manhattan, Fight for $15 has succeeded in raising the minimum wage in eight states and the District of Columbia, and the goal was embedded in the Democratic Party platform.

One of the movement's earliest successes came at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. A diverse coalition of native-born and immigrant workers of all races, many different job descriptions and multiple national origins banded together. Rather than let airport management mislead or threaten the immigrant workers, Fight for $15 organizers proactively educated them on their rights. Ultimately, a ballot initiative to raise the wage at Sea-Tac passed by just 77 votes — and quickly created momentum to raise the wage in Seattle proper.

Fight for $15 is an encouraging model, not just for raising the wage, but for creating and building worker power across a host of issues — and creating a more just economy for all. We need bold goals and smart organizing, workers standing together shoulder-to-shoulder and policymakers who have their backs. That's how we'll get real, measurable results.

A path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants is absolutely necessary to strengthen the economy for all workers, and it would help make it harder for bad employers to undercut labor protections on the job. It's good that President Biden's U.S. Citizenship Act breaks the decades-old cycle of advancing opportunities for citizenship in exchange for increasing militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, and instead proposes a vastly more humane and economically competitive immigration system.

But we can do more to support all workers, immigrant and native-born alike.

Passing the POWER Act, which is included in President Biden's immigration reform proposal, would create new whistleblower protections for undocumented workers and guest workers who come forward to report labor law violations, like wage theft or sexual harassment — just like Silvia Contreras did. The Biden administration could take a whole-of-government approach and ensure that the Department of Homeland Security take administrative action to protect undocumented workers who report workplace abuses, for instance, by protecting workers from deportation as they collaborate with federal investigations and labor law enforcement efforts.

Without remedies, legal protections aren't meaningful. Instead of continuing to allow exploitive employers to weaponize the I-9 system against undocumented workers, we should focus on sanctioning employers under the federal and state labor laws whose mission is to protect all workers. That's why Congress needs to increase funding for staffing and robust enforcement at the Department of Labor, the National Labor Relations Board and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. States and localities with stronger worker protections can follow suit, too, by enacting additional penalties on employers who violate labor and employment laws, and by working with the Biden administration to ensure protections, including deferred action, to workers who are retaliated against based on their immigration status.

And we need to raise the floor for all workers — including by raising the federal minimum wage and by striking back against the decades-long effort to undermine workers' rights to organize and bargain collectively. That's why Congress must pass the PRO Act, which would put new penalties in place against employers who illegally retaliate against workers, including undocumented workers, who are participating in union organizing drives. The law would also prohibit employers from using manipulative tactics, like mandatory anti-union meetings, to coerce or threaten workers.

But policy change won't happen on its own. We also need to change the story we tell ourselves about our economy, and the role immigrant workers play in it. No more fighting from our back foot. We should celebrate the foundational role immigrants play in our society. We should reject the narrative of big corporations and conservative politicians who want us to believe that America is a zero-sum game in which any time someone else gets a benefit, it comes at our expense.

That's never been how our society works when we are living up to our values — and it's not how our economy worked when it was at its strongest.

We all do better when we all do better. Raising the minimum wage means workers have more money to spend taking care of their loved ones, which means more demand for goods and services, which means more jobs. Protecting workers from getting COVID-19 at work means they can stay on the job and contribute to our collective health and well-being. Stopping bosses from bullying or threatening undocumented workers over their immigration status means safer workplaces and higher working standards for everyone.

It's all a part of a greater whole — the policies that ladder up, the legal frameworks that enable abuses by the powerful and depress working conditions for all, the overlooked lives and deaths of people like Saul Sanchez. If we want to not simply celebrate the many ways immigrants contribute to our society, culture and economy, but ensure that immigrants are finally recognized as essential to who we are, that they are valued in our laws, workplaces and communities, then we must start by telling their stories. It is brave workers like Silvia Contreras who help level the playing field so that all workers have stronger protections. Without wavering. Without apology. That's how we can not only change the narrative around immigrants and immigration, but change our country for the better.

Shares