As I write this article, Arizona Republicans are conducting a fake audit of the 2020 election in Maricopa County, the state's major population center. The purpose of that audit, as my colleague Amanda Marcotte accurately observes, is to satisfy Donald Trump and his supporters by doing two things. First, it applies unproved conspiracy theories to the recount process in the hope of "proving" Trump actually won the state. More importantly, it demonstrates how easy it would be for Republicans to steal elections if Trump supporters and their ilk controlled the political process.

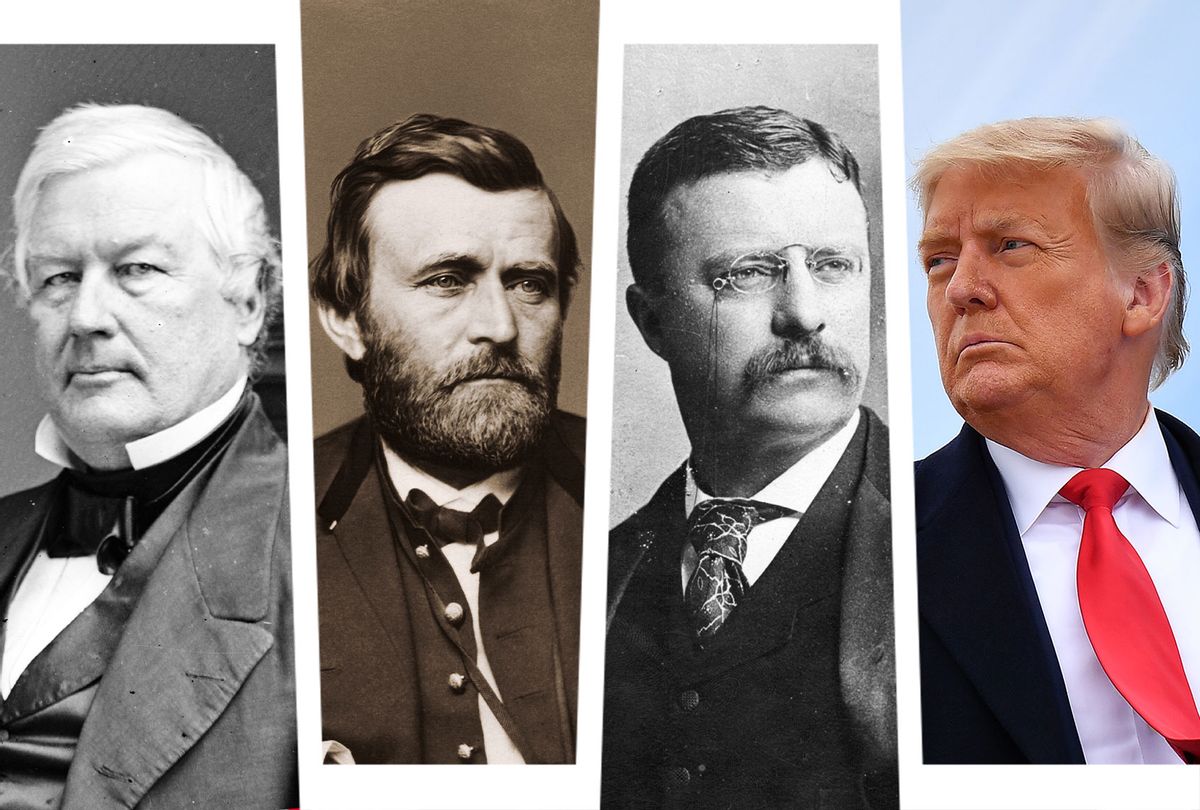

Since the most direct way for the Trump movement to gain power would be for Trump himself to be elected again in 2024, this article will look at a phenomenon that has recurred several times in American history: a defeated ex-president running again. (Only one actually won. We'll get to that.) Of course it's also possible that a future Trump-style movement could be led by a pseudo-Trump suck-up like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz or Fox News host Tucker Carlson.

The fundamental difference between Trump and other ex-presidents who have considered or attempted a political comeback is the question of attitude. Prior to Trump, former presidents who tried to run again did so by appealing to democratic instincts. Sometimes their party leaders believed they were the most electable alternative. Sometimes they ran as third-party candidates to advance causes they believed were important.

Trump, by contrast, would run in 2024 based on the assumption that power is his right, and something only he (or his sycophantic followers) are allowed to hold. He has conditioned his supporters since the 2016 election cycle to believe that the only possible outcomes when he's a candidate are that he wins the election or the election was stolen. This disturbing personality trait, which has bound many people to him through a process known as narcissistic symbiosis, is why many people (including this author) believed that Trump would try to stage a coup if he lost the 2020 election. It didn't help that, as scientists have demonstrated, many Trump supporters are also motivated by their own insecure conception of masculinity.

Trump has already destroyed many of the precedents that would stop the rise of an authoritarian dictator. He has used fascistic tactics to create a cult of personality that his party is expected to slavishly follow, has become the first incumbent president to lose an election and refuse to accept the result and has spread a Big Lie about his defeat so that his followers will believe he has a right to be returned to power. Most significantly, he actually egged on his supporters to storm the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 in a futile attempt to overturn the election results.

The good news is that the Trump movement represents a minority point of view. The bad news is, that may not matter. If Trump stages a successful comeback, it won't be viewed in normal political terms, as an ex-president losing one election and then being vindicated in another. It will be perceived as a validation of all of Trump's fascist, dishonest behavior — and will provide him all the justification he needs to stay in power indefinitely.

Nothing like that was ever the case for any of the other ex-presidents who tried to return to power. Let me clarify that I'm including some borderline cases of ex-presidents who launched half-hearted efforts to get back in the game but never waged full campaigns, as well as those who were encourage to run again by others but chose not to.

The first defeated ex-president to seriously consider another run was Martin Van Buren, who had been narrowly elected over William Henry Harrison in 1836, and then lost to Harrison four years later. (Harrison went on to have the shortest tenure of any president, dying of a severe infection after 31 days in office.) Because of Van Buren's close ties to Democratic Party founder Andrew Jackson — who had chosen him as his running mate for Jackson's second term — Van Buren was originally viewed as a leading contender for the 1844 nomination, at least until he came out against annexing Texas on the grounds that it could spark a war with Mexico (as in fact it did). Democratic slaveholders wanted to annex Texas so they could expand slavery throughout the West, so Van Buren was suddenly no longer a viable candidate. Four years later, Van Buren was nominated as a third-party candidate by the Free Soil Party, which wanted to gradually abolish slavery by prohibiting its expansion into the newly-acquired western territories.

The next ex-president to take a shot at the White House didn't do so for a noble cause. Millard Fillmore had been elected vice president as Zachary Taylor's running mate in 1848, and served nearly three years as president after Taylor's death. The Whig Party didn't even nominate Fillmore to run for a full term in 1852, and he wound up running in 1856 as the candidate of the Know Nothing Party, which was opposed to immigration and especially the large numbers of Irish Catholics then arriving in the country. Fillmore did extremely well for a third-party candidate, winning more than 21 percent of the popular vote and Maryland's electoral votes. Since the Whig Party had just collapsed, Fillmore had a hypothetical opportunity to turn the Know Nothings into America's second major party but did not even come close, with the newly-formed Republicans surging onto the scene. The Know Nothings dissolved a few years later, as did any chance of Fillmore becoming president again.

For more than 20 years after Fillmore, no ex-president actively tried for a restoration. Then, in the 1880 election, a powerful faction of Republicans wanted Ulysses S. Grant to be their nominee, even though the Civil War hero had already served two terms, leaving office in 1877. Rutherford B. Hayes, the president elected in the notorious compromise of 1876, was not running again, and Republicans needed a candidate. (The 22nd Amendment had not yet been passed, so there was no legal impediment to Grant running again.) Grant had been a great general but controversial president, due to a series of scandals that beset his administration, but was still a widely beloved figure. The Republican convention was sharply divided between Grant's supporters and his opponents. Although Grant had more delegates than any other candidate, he could not muster a majority, and delegates eventually united around a compromise candidate, James Garfield, who went on to win the election.

Twelve years later, in 1892, the above-referenced Grover Cleveland became the first and only ex-president to be elected to a second, non-consecutive term. There were a number of reasons why that worked: Democratic leaders trusted Cleveland's conservative economic philosophy and thought he was electable, which was reasonable enough, since Cleveland actually won the popular vote in 1888, despite losing the election to Benjamin Harrison (grandson of William Henry Harrison), who had become unpopular amid an economic downturn. There were no primary elections to select a party nominee, and Cleveland was well known and well liked by leading Democrats.

That brings us to Theodore Roosevelt, who had become president in 1901 after William McKinley's assassination and was then elected in his own right in 1904. After leaving office in 1909, replaced by his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, Roosevelt became dissatisfied with Taft's leadership and the Republican Party's direction. He first tried to wrest the Republican nomination away from Taft in 1912, and when that failed, wound up running as the nominee of the Progressive Party. Roosevelt didn't win the election but outperformed Taft in both popular and electoral votes — his 27 percent share of the popular vote remains the largest proportion won by any third party candidate ever — and for better or worse was instrumental in the election of Woodrow Wilson.

That was the last serious campaign mounted by a former president, nearly 110 years ago. The gradual emergence of the primary system probably has something to do with that, as does the growing cynicism among Americans about politicians perceived as "losers." Other former presidents, including Herbert Hoover and Gerald Ford, have considered running again, but none has actually done so.

Until, perhaps Donald Trump.

No previous ex-president was anything like Trump, as is blatantly obvious. Of course they were ambitious, but none of them tried to argue that the presidency was his God-given right. None urged the kinds of party purges that Trump and his crew are leading against "disloyal" Republicans like Mitt Romney and Liz Cheney. None of them flat-out lied about the reason why they'd lost power or urged anti-democratic means in order to reclaim it.

Right now Republicans across the country are pouring millions into voting restrictions, clearly targeting Democratic voters, primarily people of color. They hope to win elections simply by preventing certain voters from exercising their constitutional rights. Even if this gambit fails in the near term, Republicans have laid the foundations for overturning unfavorable outcomes. They can simply appoint loyal Trumpers or GOP partisan to the right positions to ensure that they can win even if they lose, and then create another Big Lie to justify their behavior.

It is entirely conceivable that Trump could become the first ex-president since Cleveland to be elected to another term, given the potential effects of these voter suppression laws and the ardor of his supporters. Whether we will still have anything left that could be called a democracy, if that happens, is anyone's guess.

Shares