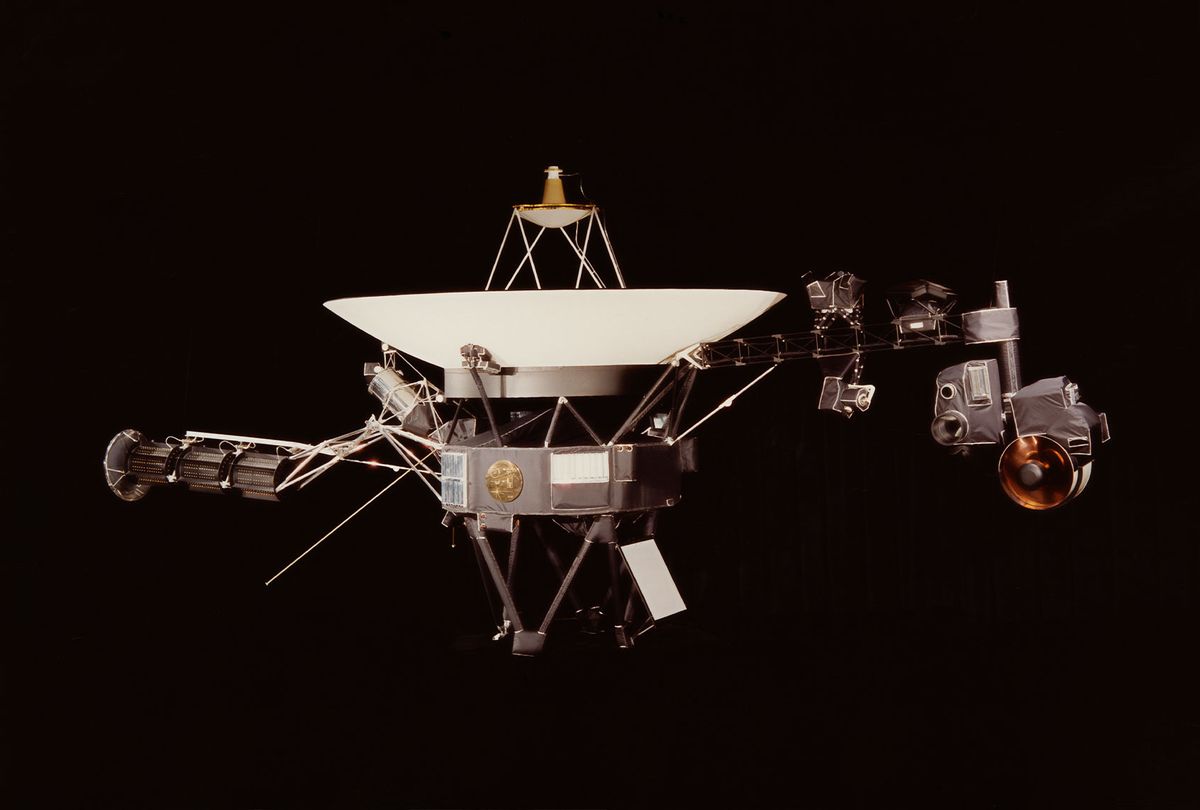

The Voyager 1 spacecraft holds the record for the most distant human-made object to ever exist. Though it was launched 44 years ago and is over 14 billion miles away from Earth, this space probe continues to send critical information and data back to Earth even as it floats through the void between our solar system and the next.

What is this vast, empty void between stars like? It turns out that the galaxy has a hum, not unlike the static you might hear when you're moving the dial between two radio stations.

On Monday, scientists published research in the journal Nature Astronomy analyzing the data that Voyager 1's Plasma Wave System (PWS) sent back to Earth after it passed through our solar system's theoretical border — a region of space known as the heliopause, where the effect of our sun's solar wind on space and celestial objects is believed to end.

Notably, the PWS detected a low, unexpected emission pattering against its detector.

"It's very faint and monotone, because it is in a narrow frequency bandwidth," said Stella Koch Ocker, a doctoral student in the Department of Astronomy and Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, who is also the lead author of the study. "We're detecting the faint, persistent hum of interstellar gas."

In other words, the constant hum of "interstellar gas," also known as plasma waves, lingers at our solar systems' borders. Interstellar gas refers to the mix of radiative, gaseous matter that exists in between star systems and galaxies; it mostly consists of hydrogen and helium in various forms, including ionic, atomic, and molecular. The pitter-patter that Voyager 1 detected gives insight into how interstellar gas interacts with solar wind, along with the overall density of the heliopause region.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

"The interstellar medium is like a quiet or gentle rain," said senior author James Cordes, an astronomy professor at Cornell University. "In the case of a solar outburst, it's like detecting a lightning burst in a thunderstorm and then it's back to a gentle rain."

Voyager 1 launched in September 1977, and famously flew by Jupiter in 1979, and then Saturn in 1980. The spacecraft travelled at 38,000 miles per hour when it passed through the heliopause in August 2012. Its nuclear battery grants the craft a very long life, hence its ability to continue sending data for decades. Indeed, researchers continue to be amazed at how Voyager 1 has gleaned new details about the solar system with multiple generations of scientists and astronomers.

"Scientifically, this research is quite a feat. It's a testament to the amazing Voyager spacecraft," Ocker said. "It's the engineering gift to science that keeps on giving."

Cornell research scientist Shami Chatterjee said in a press statement that evolving knowledge of the density in interstellar space is important information to track.

"We've never had a chance to evaluate it. Now we know we don't need a fortuitous event related to the sun to measure interstellar plasma," Chatterjee said. "Regardless of what the sun is doing, Voyager is sending back detail. The craft is saying, 'Here's the density I'm swimming through right now. And here it is now. And here it is now. And here it is now.' Voyager is quite distant and will be doing this continuously.

Shares