Every few years, Americans seem to collectively "discover" mushrooms — again. In the '90s mycologist Paul Stamets began alerting us to mycoremediation, the power of fungi to clean up oil spills and pathogen-contaminated soils. There was Michael Pollan in 2006 in "The Omnivore's Dilemma", foraging for chanterelles and morels and explaining how fungi regenerate forests after fires. A swell of enthusiasm for mushrooms of the psychedelic variety that kicked off in the 1960s is currently renewed, with ongoing research teasing out the ways they might mitigate depression and anxiety, reduce OCD, and help smokers quit. Research continues, too, into medicinal and adaptogenic uses for mushrooms — ways that certain species may help the body fight off disease or adapt to stress. Each wave of interest is accompanied by a flurry of new books (see our roundup, below).

And yet, despite their rich, established history in non-Western cultures, and each new American wave of discovery about the power and relevance of mushrooms, most of us remain unaware of their essential functions to our planetary systems and habitats. While fungi can provide the basis for a tasty and nutritious foraged meal or get steeped into a beverage that may boost our immune systems, they thread together our ecosystems. This is where their true, critical, purpose lies.

Kingdom Fungi is made up of an estimated 3.5 million species — including molds, yeasts, lichens — that began evolving on Earth 1.3 billion years ago. Any farmer or botanist can tell you how important they are to building up soil; keeping plants that grow in that soil healthy; and breaking down all the plant-based (and some animal-based) dead matter that our planet's various working systems generate. "Otherwise, we would be covered in trash and most other biological processes on Earth would stop," says Jennifer Bhatnagar, an assistant biology professor at Boston University who studies decomposition. That rotted matter is then converted right back to soil, and to nutrients that feed the plants growing in it.

For a preliminary glimpse at what fungi do, and how, see our soil primer. Here, we delve deeper to elucidate the ways in which fungi are so critical to the way so many things work on our planet.

Click here to view a larger version of this graphic

Decomposers

First, there are the decomposers. These can take pretty much any material — even a manmade one like plastic, rubber, concrete, the nuclear reactor core at Chernobyl, says Bhatnagar — and break it down. "When you decompose dead stuff, that stuff releases elements," says Bhatnagar. "Fungi are looking for carbon and they'll take that up and put it into new molecules in their biomass" — basically, use it as food in order to grow themselves. Other released elements — mostly nitrogen and phosphorous — are converted by fungi to ammonium, sulfates, and phosphates. These are the forms that plant roots are able absorb and use. Says Bhatnagar, "Fungi are essentially providing plants with nutrients, recycling them from dead plants back to live plants."

Decomposer fungi — and there are lots of different kinds of them, each with a special function with regards to a specific plant or other organisms — are found in the soil as well as on the surfaces of leaves, bark, stems. Some of them are waiting there for the plant to die before breaking down the specialized part — leaf, bark, stem — they're associated with. Other decomposer fungi arrive on a plant after it has died and get to work on its heart wood or its largest branches, for example. Many decomposers also sometimes act as parasitic fungi, invading a plant and causing disease or even death.

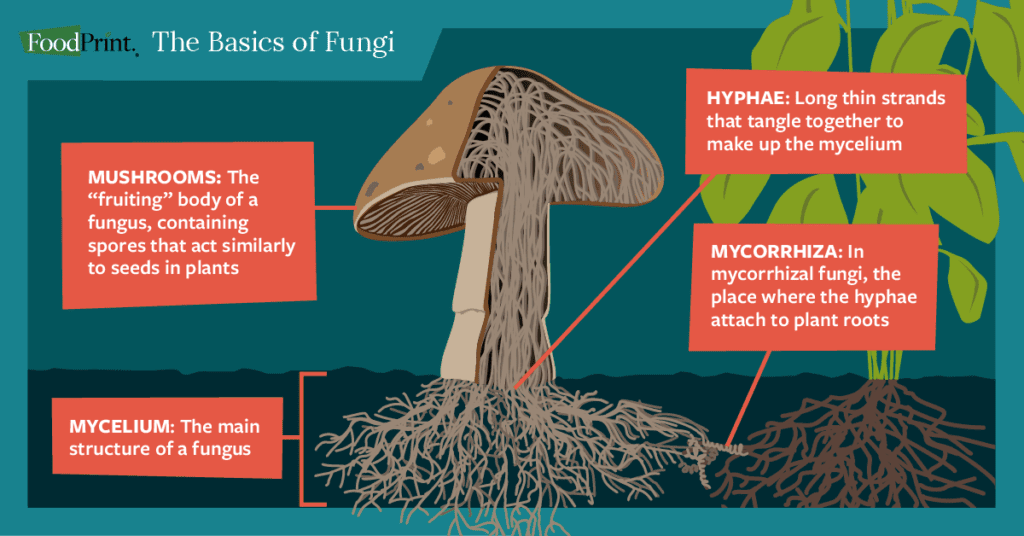

Partners

Then there are the partner fungi. As far as we know, 90% of all plants, maybe more, have mutually beneficial relationships with fungi; the types of plants and fungi that partner with each other differ depending on soil, habitat, and so on. When they live in soil, these fungi — in this instance referred to as mycorrhizal fungi — create what's known as the mycorrhizae, where they come together with a plant's roots; through that connection, the plant funnels carbon and sugars to the fungus and in return, the fungus, says Bhatnagar, "extends its hyphae into the soil to explore it for decomposed dead matter" to supply nutrients and water to the plant.

However, there's even more benefit that these and other "helper" fungi impart to plants. Some colonize the outer, above-ground surface of a plant — its phyllosphere; some, called endophytes, live inside plant tissue. They "stimulate plant hormones, to give them protection to fight off pathogens," says Bhatnagar. "Or they can confer tolerance to different environmental conditions, like heat or salt stress. They are important to plant survival."

There are also fungi that partner with mammals, living inside their guts and helping them to digest; and others that partner with algae and bacteria — including some that allow certain extremophile bacteria to live in hot springs and withstand scalding temperatures.

Fungi and climate

In addition to forging individual relationships with plants and keeping Earth tidy, fungi collectively have broader relevance to keeping our planet habitable. Fungi that live in soil are the "major conduits of carbon sequestration on land in our terrestrial ecosystem," Bhatnagar says. This is a not insignificant function; land is the second-largest carbon sink on Earth, after the ocean, holding almost 30% of what we store for a massive climate benefit.

Fungi also contribute to keeping the temperature of our planet in balance. They do this by emitting CO2 — although, with climate change rapidly heating up our atmosphere, researchers are trying to better understand how fungi and climate might now be affecting each other.

In fact, not knowing permeates many aspects of mycology. As Bhatnagar explains, only a couple hundred fungal species have so far been scientifically described and although we are getting better at figuring out how they work — alone, in groups with other fungi, with plants, and so forth — there are still massive question marks regarding much of the Kingdom and how it operates.

Leaving these questions unanswered could have dire consequences for our planetary systems and our food supply. "We don't know how redundant [groups of fungi] are, or exactly what they do," says Bhatnagar, while pointing out that we might be unwittingly causing fungal, plant, and soil death when we move fungi out of their native ranges. For example, hyphae can remain alive in wood chips used for mulching, and the mulch you purchase at the nursery could have originated almost anywhere.

In parts of the global South, monocultures of pine trees planted in vast tracts for lumber are becoming invasive species — escaping their plantations to outcompete native trees, helped along, a study by one of Bhatnagar's post-doctoral researchers shows, by their fungal partners, which are also behaving as invasive species.

Bhatnagar expresses apprehension at watching bulldozers stripping the soil to renovate a playground across the street from her house in Massachusetts: "They're bringing in from who-knows-where who-knows-what organisms, and we have no idea how well they will survive there, or how they will interact with plants," she says.

These are not just broad philosophical concerns. There are now 280 fungi on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species. The danger, says Bhatnagar, is that even as we're learning more about the traits of fungi and what they do for soil and plants, "It's possible we are losing things that are important to ecosystems and the ability of plants to survive the stresses of climate change." Once fungi are gone, they may not come back and that makes it unlikely that we'll recover the functionality they provide. "There's a carelessness to our interactions with soil that is pretty detrimental to the plants we care about," Bhatnagar says. She hopes that people will start to recognize that fungi are important, and fragile, and "not as resilient as we think."

8 new books about mushrooms and fungi

However, one thing we're not doing wrong with and for fungi is foraging; a long-term study of foragers in Switzerland shows that picking merely their fruiting bodies — that is, mushrooms — does not have a negative impact on future mushroom yields or species richness of mushrooms out in the forest. Still, we should behave respectfully to all living things and ecosystems while out there; here's a handy guide to staying safe in the wild, and to ethical foraging. Meanwhile, the books below will get you up to speed on identifying fungi species, including those that are good to eat, as well as cooking and storing them, growing them, and thinking about their numerous uses to humans and our planet.

"The Beginner's Guide to Mushrooms" by Britt Bunyard + Tavis Lynch

This field guide geared towards absolute beginners offers myriad photographs to help you locate and identify fungi in the wild. In addition to providing a reference to some North American species, two brief chapters cover cultivating fungi as well as cooking what you grow and find — with recipes.

"Entangled Life" by Merlin Sheldrake

"[A] fungal network laced out into the soil and around the roots of nearby trees," Sheldrake, a British biologist, writes in his introduction."Without this fungal web my tree would not exist. Without similar fungal webs no plant would exist anywhere. All life on land, including my own, depended on these networks." It's these webs that Sheldrake sets out to explore and elucidate in this natural history flecked with personal anecdotes. Interested in building on what you've just learned in a fungi primer? This is a great next step along your educational journey.

"Fungarium: Welcome to the Museum" by Ester Gaya

This latest in a series of large, vividly illustrated books that function as a cabinet of curiosities — other titles include "Animalium", "Botanicum", and "Historium" — is aimed at kids but is too gorgeous, intricate, and intriguing for them not to share it with their grownups. Together or individually, you can pore over the informative text to learn about mushroom habitats and ecosystems. Or just spend hours gazing at the intricate and mesmerizing illustrations.

"In Search of Mycotopia" by Doug Bierend

Food and science journalist Bierend tells some of the myriad stories of fungi and their functions in ecosystems through the people who study, cultivate, and wield them and their powers. From the Kew Gardens researchers cataloguing fungi for inclusion on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, to conservationists using fungi to clean water and other habitats, this is both a fun and educational readthat helps map the reach of this diverse and critical Kingdom.

"Mushroom Wanderland" by Jess Starwood

For those interested in identifying mushrooms for the distinct purpose of eating them, "Mushroom Wanderland" provides detailed instructions on how to identify 12 of the edible kind that are good for cooking with — think puffballs, morels, and porcini; six with purported medicinal uses, like reishi and turkey tail; and several that are toxic or poisonous. Punctuated with color photographs and descriptive text that passes along some of a forager's best secrets about when/where/how, as well as storing tips and recipes, this book acts as both a practical and spiritual guide to appreciating mushrooms and caring for the landscapes that foster them.

"Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms" by Marl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsten McKnight + Kent H. McKnight

This uncommonly beautiful field guide to almost 700 mushrooms found across North America is a great starter tome for anyone who's ever taken a hike after heavy rains and wondered what all those mysterious and colorful organisms proliferating over fields and tree trunks were. The illustrations are sharp and clear and provide good instructional accompaniment to the detailed descriptions. Sized to fit in a daypack.

"The Secret Life of Fungi" by Aliya Whiteley (Sept. 2021)

Whiteley, usually a novelist, here gives a personal account of her discovery of the wide and wild world of mushrooms. Part mycological history, part poetic guidebook, and part philosophical treatise — interspersed with bits of memoir — this is the sort of book you'll want to read cover to cover, learning as you go without even trying.

"Wild Mushrooms: A Cookbook and Foraging Guide" by Kristen Blizzard + Trent Blizzard

This is a one-stop reference for anyone interested in foraging mushrooms — then figuring out to do with their haul. Covering everything from forest etiquette, to the various ways in which to preserve mushrooms, to 115 diverse and well-thought-out recipes for 15 different kinds of mushrooms, to tips for avoiding gastric upset and other undesired effects, this will you up your game, from novice enthusiast to connoisseur.

Shares