During last summer's racial justice protest movement, more than a few executives in corporate America leveraged their platforms to weigh in on a number of fronts: They beefed up diversity and inclusion efforts, issued public statements in support of Black Lives Matter or other ostensibly progressive political issues and, in some cases, publicly supported employees' efforts to have "difficult conversations" with co-workers, suggesting those might lead to long-term changes in the way people related to each other in the workplace.

Just as the COVID-19 pandemic has upended our connection to physical workspaces, the last year has also forced white-collar workers to rethink their relationship to office culture. At the heart of this debate is the shifting role that work, and the companies that sign our checks, should play in our lives: personal, political and even spiritual.

But other executives, particularly in the tech world, saw these efforts through a completely different lens: as distractions from the paramount or sole purpose of their business — turning a profit.

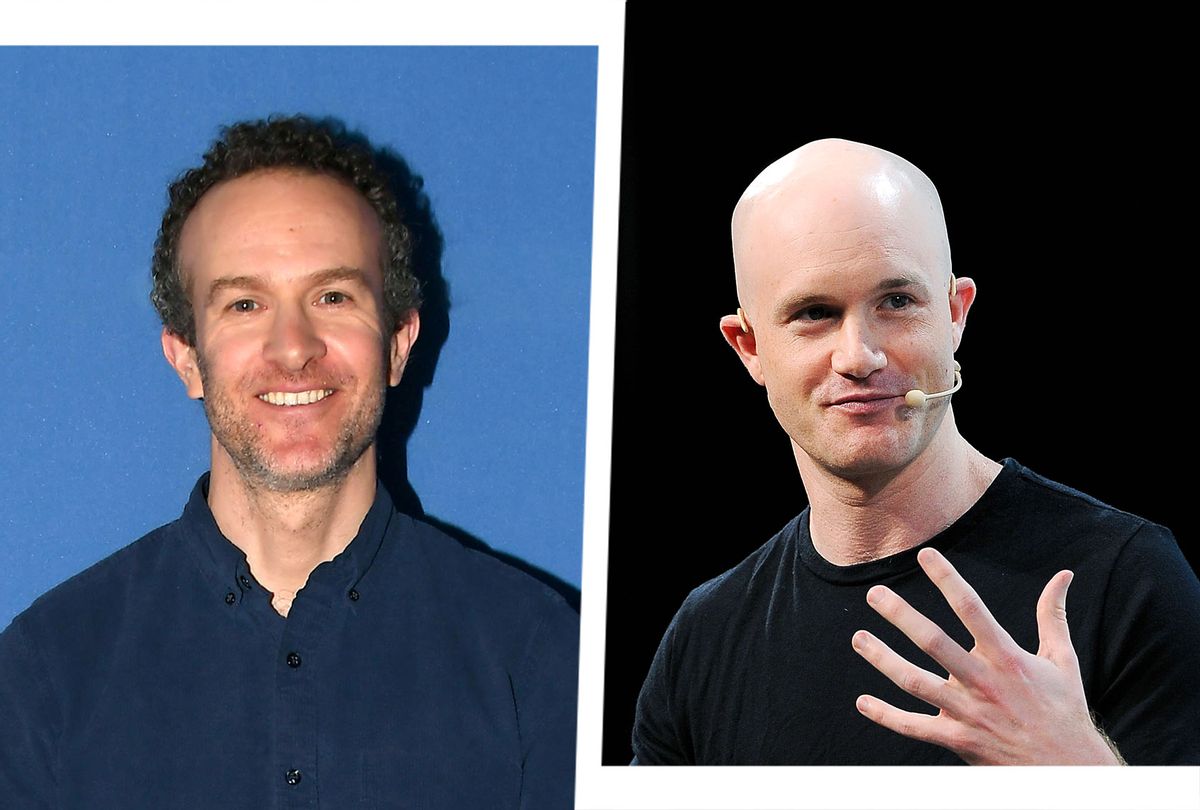

At Coinbase, a prominent cryptocurrency exchange, CEO Brian Armstrong dove headfirst into the culture war with a lengthy and influential public screed last September about his company's "mission first" mindset. Armstrong suggested, perhaps improbably, that work should be a "refuge" from the world rather than a part of it.

"While I think these efforts [to create a dialogue around social and political issues] are well intentioned, they have the potential to destroy a lot of value at most companies, both by being a distraction, and by creating internal division," he wrote. "I believe most employees don't want to work in these divisive environments." In the future, Armstrong said, Coinbase would not weigh in on social issues or support political candidates, and would not divert significant time or money to charitable causes. Employees were expected to do the same during work hours.

Many critics, both inside and outside the company, questioned how a cryptocurrency company would possibly manage to stay out of politics, given the clamor for increased regulation of the industry — but the response went unaddressed.

Armstrong extended a severance offer to any employees who didn't agree with the company's new direction. At least 60 people at Coinbase took the offer, Insider reported, about 5 percent of the company's total workforce.

Despite the turmoil it created within Armstrong's company, the post resonated with other members of the managerial class, who have spent much of the last few months parroting the sentiments in public and in private.

"Yet again, Brian Armstrong leads the way," Paul Graham, the founder of influential seed capital firm Y Combinator, tweeted in response. "I predict most successful companies will follow Coinbase's lead. If only because those who don't are less likely to succeed."

Echoes of the controversy sounded last month as Basecamp CEO Jason Fried, who helms the influential project management software firm, announced an outright ban on "societal and political discussions" on the company's internal chat features.

It was a huge win for the "mission-first" crowd — Fried, who along with co-founder David Heinemeier has authored five how-to books on productivity and business strategies, is widely considered to be a thought leader on corporate culture.

Last week, a leaked email obtained by Insider written by Tobias Lütke, the CEO of Shopify, to the company's employees also revealed similar internal policies at the Canadian e-commerce giant. We're a business, Lütke wrote, not a family. Stop trying to solve social problems on company time — that's not what Shopify exists for, and it's certainly not what employees were hired to do.

Shopify, like any other for-profit company, is not a family. The very idea is preposterous. You are born into a family. You never choose it, and they can't un-family you. It should be massively obvious that Shopify is not a family but I see people, even leaders, casually use terms like "Shopifam" which will cause the members of our teams (especially junior ones that have never worked anywhere else) to get the wrong impression. The dangers of "family thinking" are that it becomes incredibly hard to let poor performers go. Shopify is a team, not a family. …

Shopify is also not the government. We cannot solve every societal problem here. We are part of an ecosystem, of economies, of culture, and of actual countries. We also can't take care of all your needs. We will try our best to take care of the ones that ensure you can support our mission.

When Lütke wrote the email last June, Shopify had already embarked on an increasingly precarious tightrope walk. In the midst of a pandemic, an economic crisis and a contentious election year, the company was under increasing pressure to drop certain retailers from its platform, most notably Donald Trump's campaign.

It wasn't the first time the influential business-to-business platform courted controversy with its customer base. A boycott campaign over the company's hosting of an online store for the far-right website Breitbart gained steam in 2017 under the hashtag #DeleteShopify.

At the time, Lütke wrote a viral Medium post likening the company's mission to that of the ACLU (yes, really) and little came of it. In the summer of 2020 Lütke dusted off the same playbook, and was again largely successful — although the company eventually agreed to drop the Trump Organization and Trump campaign after the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

But what these viral sermons on workplace culture always conveniently fail to mention are the incidents that led to their existence.

In the wake of George Floyd's murder last June at the hands of a police officer in Minneapolis, a group of Coinbase employees reportedly staged a walkout after asking Armstong to affirm publicly his support for Black Lives Matter, and being rebuffed. That news emerged in a Twitter thread from Democratic party operative Erica Joy, and Verge technology writer Casey Newton later reported that Armstrong's letter was seen within the company as a direct response to the walkout.

Armstrong did later state his support for Black Lives Matter in a Twitter thread specifically mentioning the fatal police shooting of Breonna Taylor that March in Louisville, though Newton reported that "the post referred to the killing only as 'recent events regarding Breonna Taylor,' before the coldness of the language was mocked on Twitter and he deleted any reference to her."

Newton also broke the news that the internal discussions Fried hoped to stifle at Basecamp weren't as "political" as he had made them out to be — for several days before the CEO made his post, employees had been outraged at the existence of a list the company's customer service team had created that compiled "funny customer names," which included a number of clients of Asian and African descent. Many saw the practice as racist.

At Shopify, Lütke failed to mention that the Slack channel he shut down in accordance with his new no-more-politics-at-work diktat had become focused on a noose emoji that another employee had imported into the system.

"Beyond straight performance output, everyone that engages in endless Slack trolling, victimhood thinking, us-vs-them divisiveness, and zero sum thinking must be seen for the threat they are," Lütke wrote in his email. Some employees interpreted the language as meant to silence dissent over an increasingly toxic workplace, according to Insider.

"It's worth saying that much of what we have been discussing this summer has not been 'politics' so much it has been 'human rights,'" Newton wrote of the controversies. And many of the employees he spoke with agreed.

One Basecamp employee said that the "political discussions" the CEO was so eager to shut down had "always been centered on what is happening at Basecamp." The topics included "What is being done at Basecamp? What is being said at Basecamp? And how it is affecting individuals?" this person said. "It has never been big political discussions, like, 'Should the postal service should be disbanded?' or 'I don't like Amy Klobuchar.'"

These incidents are also inspiring a new wave of activism within the tech world. Executives at Amazon, Salesforce and Pinterest, for example, have been forced to respond in various ways to an increasingly vocal workforce — especially on the issue of sexual harassment.

The most successful group of these white-collar employees works at Google, where several hundred formed a union earlier this year. Organizers say their goals are not necessarily to agitate for better pay or benefits, but to overhaul the industry's culture, diversity and ethical considerations.

"Our goals go beyond the workplace questions of 'Are people getting paid enough?' Our issues are going much broader," Chewy Shaw, a San Francisco-based engineer and union vice chair, told The New York Times. "It is a time where a union is an answer to these problems."

They hope the union push can also counter Google's leap into a range of dystopian technologies: developing artificial intelligence for the Defense Department and offering facial recognition to immigration authorities, for example.

Precisely the sorts of topics that management doesn't want workers to talk about.

Shares