In January 2021, when the COVID-19 vaccine was still in short supply, reports began to surface that thousands of the coveted doses were being tossed in the garbage.

“They’re a precious commodity, so why are some COVID-19 vaccines going to waste?” NPR asked. “Thousands of COVID-19 vaccines wind up in garbage because of fed, state guidelines,” NBC News reported.

The news was at odds with the pandemic’s toll, just as a holiday surge in gatherings led to a record surge of U.S. COVID-19 deaths in January. It turned out that vaccine doses were being thrown away for a variety of reasons — including patients missing appointments and a lack of infrastructure for distributing leftover doses when already-opened vials had more doses than expected.

Then there were the logistical issues. Local governments had their own regulations on how physicians could distribute the vaccines, including fluctuating eligibility requirements. In Texas, one doctor who gave away vaccine doses that would expire within hours was fired from his job. Then were also problems with shelf life and storage, in that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines must be stored at sub-zero temperatures — and, once thawed, have only a five- to six-hour life.

In other words, efficient distribution of leftover doses was an urgent issue that needed to be solved. It was also the exact kind of a logistics problem that appeals to the magical thinkers of Silicon Valley — people like tech entrepreneur Cyrus Massoumi, previously the founder of physician database and telehealth platform ZocDoc. The company he started to “fix” the problem of wasted vaccines was called, simply, Dr. B — named after Massoumi’s grandfather, nicknamed Dr. Bubba, who became a doctor during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

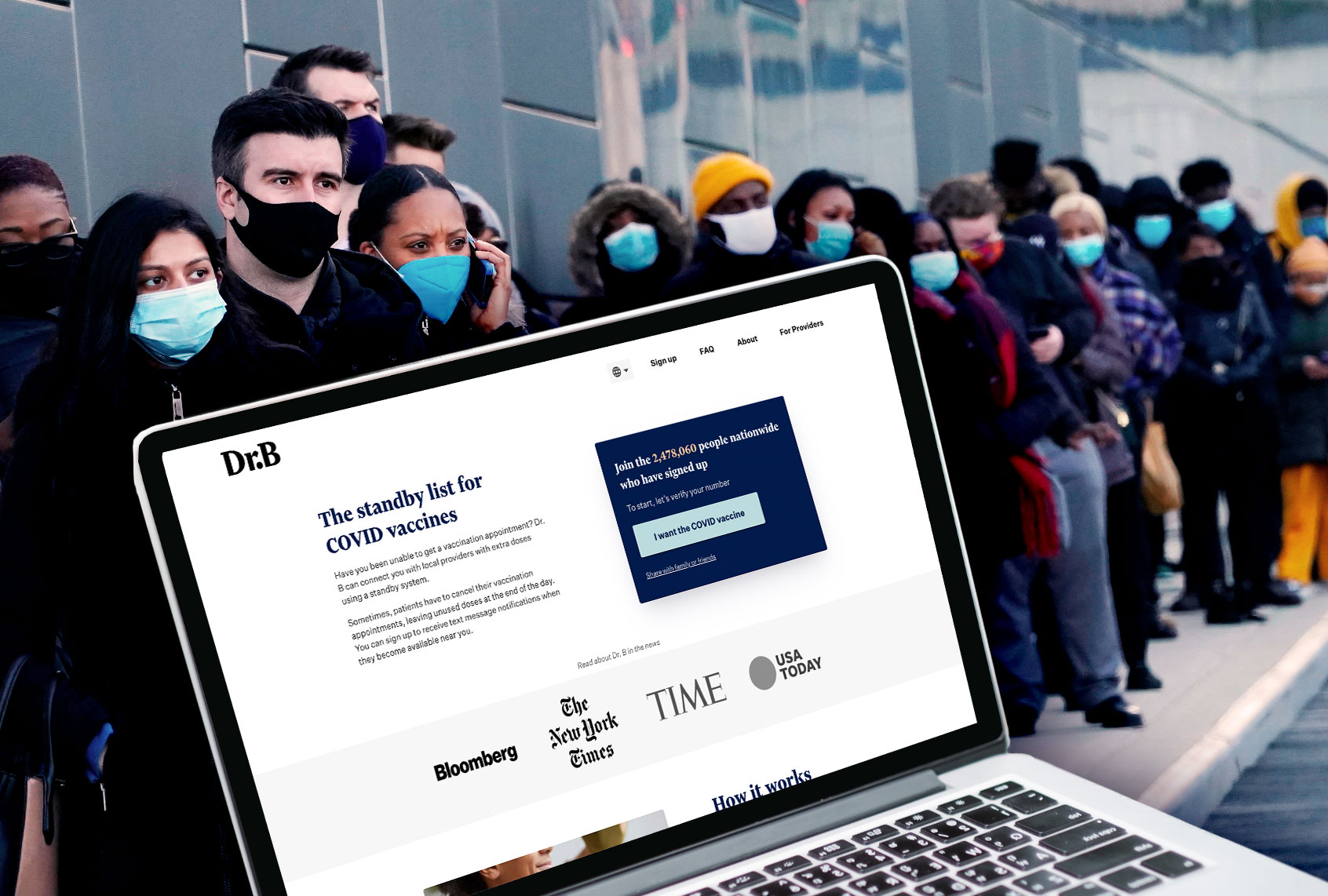

Here’s how Dr. B was supposed to work: Users provide the website with personal data — namely, their home phone number, zip code, date of birth, and, optionally, underlying health conditions. Dr. B then adds them to a “standby list” that connects patients needing the COVID-19 vaccine with healthcare providers who have leftover doses and need to administer them before they expire. Users then get a text immediately when there’s an opening, and must respond within a short span of time to be able to get the leftover vaccine. The whole system was free.

The concept sounds simple, but the execution is more complicated than it looks. And notably, Dr. B sought to solve a logistics problem (efficient vaccine distribution) by creating a second logistics problem: calling thousands of vaccine providers around the country to sell them on using Dr. B’s system to distribute leftover doses.

In any case, Massoumi wasn’t the only one who had this idea. A competitor with a more intuitive name, VaxStandby, was created around the same time — yet it quickly “joined forces” with Dr. B, which proceeded to gain tons of media attention in early March from outlets ranging from The New York Times to The Verge. By March 10, Dr. B had an estimated 1,110,822 subscribers, who had given their personal information over to the site.

The list continued to grow. But as time passed, some of the website’s user base became increasingly suspicious: on social media, many users wondered if the site was a scam. A handful of Facebook users asked the same thing in vaccine hunter Facebook groups nationwide. “Seems like they did a better job of marketing themselves than of connecting with vaccine providers,” one user wrote. On Reddit, too, many suspected they had been “scammed,” and used that verbiage. “Where is the stat for how many received a vaccine through the service?” asked one Reddit user seeking clarity over whether the site was legit.

Meanwhile, Dr. B’s business model — offering a free service in which the users pay no money — raised eyebrows. After all, as the old Silicon Valley maxim goes, if the service is free, you are the product. And Dr. B provided little information on how many of its million-plus users had actually received a vaccine through the site. That raised questions for many: How many vaccination sites were actually using Dr. B? What was the long-term goal for the site? And what happened to all the user data it was given?

To date, after contacting dozens of state vaccine providers across the country, only a couple of vaccination sites were able to confirm to Salon that they use the waitlist. Despite repeated requests for specific providers, spokespeople for Dr. B haven’t been able to direct Salon to specific vaccination sites.

On April 7, a spokesperson for Curative — a company that launched in January 2020 to test for sepsis, but pivoted to COVID-19 tests — told Salon via email that the Berkeley site had been using the app for three weeks, and that it would start to use it soon in Sacramento. However, at the Berkeley site, the spokesperson said they only use the website for a maximum of five people per day. “If we had to open a vial for the last appointment, then using Dr. B to finish the rest of the doses from that vial, for example,” the spokesperson said.

After posting in several vaccine hunter Facebook groups, Salon has also yet to find someone who was successfully vaccinated through the app. Some reported finally receiving notifications, but only after they were vaccinated in late April and early May. On April 9, Massoumi told Salon in a video interview that he didn’t know how many people had been vaccinated through his website.

“To put it in context, we didn’t exist two and a half months ago and everything that we’ve been doing is to make sure that we’re getting vaccines in arms,” Massoumi said. “We actually don’t yet have a data warehouse, it’s just not where we prioritize engineering; it’s not needed to get vaccines in arms, it’s needed for entering questions like you’re asking.”

Massoumi said that the number of vaccine sites using the app was growing “very quickly,” and that it numbered over 150 by April 9 — including in New York, Alabama, California, and Arkansas. More recently, the company’s PR spokesperson claims to have over 600 sites in more than 38 states. When Salon contacted the New York State Department, Erin Silk of the New York State Department of Health press office said “New York State-run vaccine sites do not use Dr. B.” Private providers, Silk said, might.

A spokesperson for Dr. B denied the claim that New York state-run providers don’t use the waitlist. In a follow-up, Silk confirmed that New York state sites aren’t using the waitlist. “Perhaps the vendor is confusing us with county-run sites,” Silk said in an email.

Arrol Sheehan, a public information office for Alabama’s Department of Health, told Salon via email that Alabama county health departments weren’t using the standby list either, but said “we cannot speak to what the other providers are doing.” In Arkansas, John Vinson, CEO of the Arkansas Pharmacist Association, told Salon there were at least three sites in Central Arkansas that are using it. However, by early April the association forecast little need for the service in the future as demand for the vaccine declined in Arkansas.

Despite its limited areas of operation, users who sign up for Dr. B have no way of knowing if the website is operating in their local jurisdiction or not upon sign-up. On March 9, 2021, an article published in Time reported that there were two sites in New York and Arkansas piloting the website, but on the website itself there was little information to communicate that this was still in a piloting phase. Still today, on the website’s FAQ page, one question asks “Where is the service available?” to which the company responds “Currently, we are only operating in the United States.”

* * *

The operational logistics of Dr. B seem expensive, particularly for a free service: it costs money to run servers, to hire people to call thousands of vaccine distributors, to build a website and a database to track vaccinations. In interviews with the CEO and other members of the Dr. B PR team, Salon was unable to gain a clear picture of the business model for Dr. B; many aspects of the company’s finances — who is funding it (and why), as well as what they expect to get in return for their investment — are unclear.

It’s not uncommon for tech startups to begin their days by offering a free product. If they can show venture capitalists that their product will be popular later, seed funding is justified after the fact. Facebook, YouTube and their ilk began this way, offering a free product in order to attract a huge user base. Now, they make hefty profits selling their consumers’ data to better target advertisements, or in some cases offering consumers premium services.

But in the case of Dr. B, both the eventual financial windfall and the case for seed funding are unclear. The pandemic will end eventually — already in many regions, vaccine supply outweighs demand. These conditions supersede the need for a service like Dr. B provides.

The company states it is a “public benefit corporation,” a type of for-profit organization with a social mission. “Public benefit corporations were introduced to enable you to be a private company which would be a for-profit business, but you have your mission and your charter so you can very much align with what the end goal is,” Massoumi said.

When asked about the revenue model, Massoumi said “Dr. B makes no money . . . it’s free for patients, it’s free for providers.”

When Salon asked Massoumi how he paid for 40 consultants, which he said he hired, Massoumi replied he paid them out of pocket. In a follow-up with a new PR agency for the company, a spokesperson said that the company later raised funds from private individuals and organizations. No further details on the investors were provided.

“Our mission is to improve efficiency and the equity of healthcare,” Massoumi said. “As of now, we’re just trying to get as many people to the vaccine as possible.”

As of May 13, Dr. B has a huge cache of users’ personal data — including phone numbers, names, emails, zip codes, dates of birth, professions, and in many cases specified health conditions — for over 2.4 million people. Massoumi emphasized that the data is safe, and a spokesperson for the company said Dr. B has “the best healthcare engineers” with “years of experience dealing with privacy, security, and patient needs.”

“Patient data is encrypted at rest and in transit, and is stored in a secure database in an isolated network, not accessible from the outside world,” a spokesperson said.

And yet, in its privacy agreement, the company states that it can’t guarantee a person’s data will not be viewed by unauthorized persons. When asked why, a spokesperson said: “We leverage our team’s expertise to do everything we can to protect patient data. Like other technology companies, we cannot guarantee that bad agents will not attempt to breach our security system.”

Eric Goldman, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law who specializes in the tech industry, said when a website like Dr. B has such a large amount of data it is difficult to protect it from a potential hack. As Goldman explained, it can be a challenge for “smaller apps” to be “prepared for the malefactors to come at them.”

“You can never prevent the bad guys from getting in,” he said, mentioning criminal hackers and state sponsored hackers as examples. “And those people can overwhelm a small site like. Dr. B. There’s just no way to have industrial grade security against determined adversaries like that.”

Goldman clarified that this was not a criticism of Dr. B specifically, but instead of the “whole model” exemplified by tech companies that collect massive troves of user data.

“When you create a honey product of 2.4 million plus records with health information, everyone wants a piece of it,” Goldman said.

Dr. Richard Forno, assistant director at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Center for Cybersecurity, told Salon in an interview that there is great value to personal medical information.

“That’s useful information if you’re a bad guy, especially during the pandemic,” Forno said. “A criminal group, whomever, could parse that data, and they could use that to target people with phishing attacks or social engineering attacks — to get them to maybe fork over additional information or maybe give a credit card number to reserve their spot in line or prepay their vaccine shot.”

Forno emphasized that phishing concerns aren’t specific to Dr. B, but to many websites that have collected data during the pandemic.

“There are so many different ways that medical data PII [personally identifiable information] like this can get out there these days,” Forno said. He noted that there’s been an “increase in popularity and value” of medical data to criminals. “I think the pandemic really put it into overdrive,” he added.

In March 2020, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) called on California Governor Gavin Newsom to put in place basic privacy guardrails on any contact-tracing program run by or in conjunction with the state, as new organizations, like the coronavirus testing website Verily, started popping up collecting data for purposes shaped by the pandemic. The rise of Verily, a sister company to Google under the Alphabet umbrella, also raised privacy and data use concerns.

As part of the EFF’s proposed requirements, they asked for companies to purge data from such programs when it is no longer useful. When asked if Dr. B had a plan to purge data when it’s no longer useful, a spokesperson said “people can choose to unsubscribe or delete their data at any time.”

Forno reviewed Dr. B’s privacy agreement and said there were no “showstoppers” in terms of red flags, but agreed there is a trend throughout the agreement that places the onus on the user; for example, the mere fact that the company apparently has no plan to purge the data when it’s no longer useful. Forno said he believes it’s “absolutely” the company’s responsibility to purge PII when it’s no longer needed.

“If you set this up as a short-term thing, and you know, the pandemic is over in six months or whatever, and you decide we’re going to shut the site down, then absolutely it’s Dr. B’s responsibility to purge the data in a safe and secure manner,” Forno said.

In regards to social media chatter suggesting the website is a “scam,” Massoumi told Salon, “I guess I would ask you, are those people that are in the highest priority criteria, and are they in areas where the vaccine providers have come on?”

“We told people from the very beginning, this is intended to be a plan B,” Massoumi said. “Dr. B is not the plan A — this is the backup option. People should still go to their vaccine locations, they should go to their public health officials, whatever their local governments tell them to do they should go do.”

Massoumi emphasized, “We have been very clear to the whole world” that people would not be eligible through the app because of local eligibility requirements or because sites weren’t available in their jurisdictions. Some users who signed up to join the waitlist might disagree — though many of those who signed up never heard from the app.

While not disclosing the limitations of a business’s service may not quite be illegal, it does seem to approach some ethical guardrails.

“We call that ‘false advertising by omission’ — it’s not what they said was wrong, but it’s incomplete in a way that might create a false impression among the consumers,” Goldman said. “Omission cases are really tough, because we know that the businesses can’t tell us everything that might be relevant to any particular consumer — they have to pick and choose what information they expose.”

Since Salon interviewed Massoumi, vaccine eligibility has expanded to everyone over the age of 12 across the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has advised vaccine providers not to forgo an opportunity to vaccinate someone who wants the shot — even if that means opening a new vial, which includes multiple doses, for one person. In other words, there are few waitlists for vaccines. The logistics problem has shifted from one of scarcity to one of excess.

In a follow-up with the company’s PR firm, Goldin Solutions, Salon asked about the strategy moving forward. Is there still a purpose for Dr. B’s waitlist?

“Dr. B was created during the height of the COVID-19 crisis with the clear mission to save lives by rapidly getting vaccines into as many arms as possible because too many vaccines go to waste,” a spokesperson said via email. “We are proud to have helped nearly 2.5 million people sign up for notifications about immediately available vaccines through hundreds of providers nationwide; as the vaccination effort in the U.S. moves forward, we are working with a number of partners, community organizations and healthcare providers to remove the barriers that are continuing to prevent people from getting vaccinated.”

In a final follow-up, a spokesperson did not provide a number for how many people had actually been vaccinated through Dr. B.