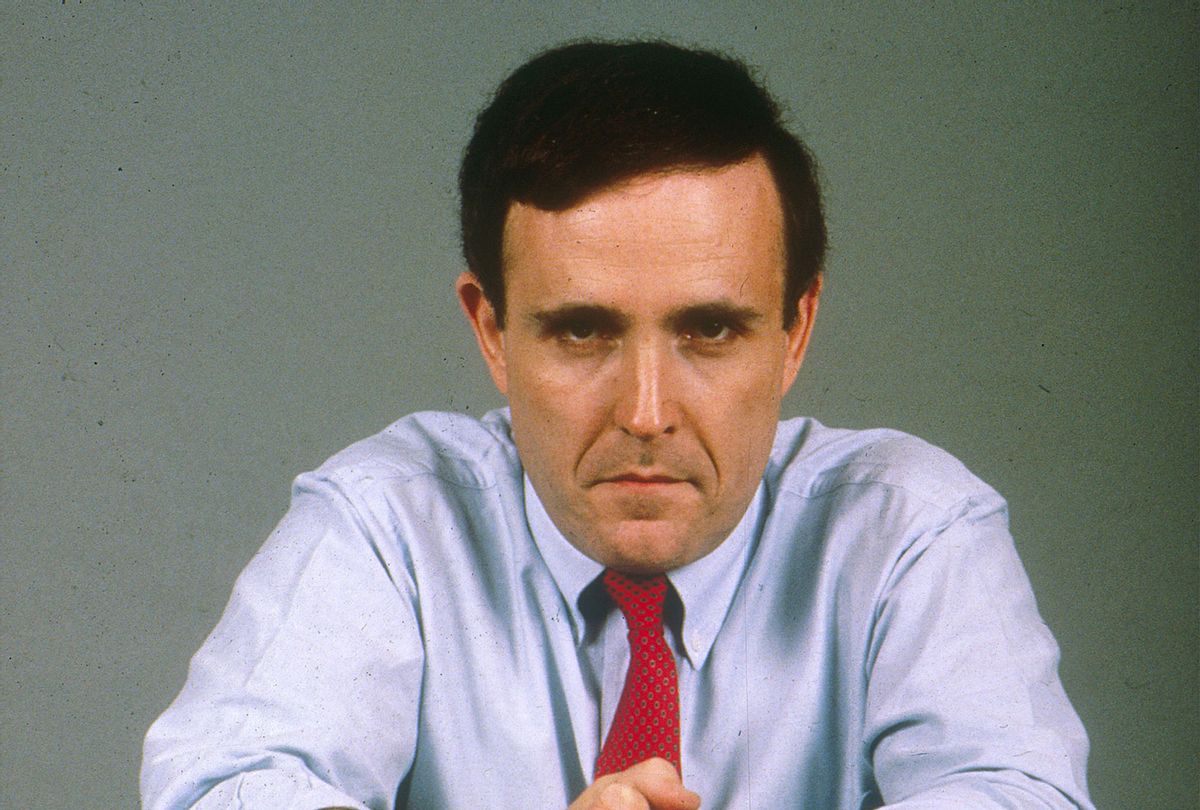

What has become of Rudy Giuliani? Once the celebrated hero of 9/11, he has become, thanks to his association with Donald Trump, the subject of investigations by the government he once led.

No longer a hero, save to those on the far right, he seems only a subject of ridicule or, more darkly, a felon facing jail time. What could I, a retired college professor who has never met Giuliani, add to the national debate about "America's mayor?"

It's true that I've never met Giuliani, but our paths once did cross more than 30 years ago in an episode that reveals something about Giuliani's character that perhaps helps us understand his later downfall.

In the mid-1980s, early in my career as a historian, I began to research the life of William W. Remington. Born in New York in 1917, educated at Dartmouth College and Columbia University, Bill Remington seemed to have it all — brilliant, ambitious and as handsome as a movie star, he appeared destined for a distinguished career in American government.

Then, in 1948, came the accusations that destroyed Remington's career. He was charged with being a Communist and a Soviet spy during World War II by ex-Communist Elizabeth Bentley, and spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name. His days became an endless series of appearances before congressional committees, government loyalty boards, grand juries and, after being indicted for perjury in 1950, judges and juries at federal trials. Eventually, he was convicted of perjury and sentenced to serve three years at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, where, in November 1954, he was murdered by other inmates. He was 37.

One of the most bizarre chapters in Remington's story concerned his indictment for perjury in June 1950. Shortly before his first trial, Remington's lawyers learned that the foreman of the grand jury, a poet named John Brunini, had a close personal and financial relationship with Remington's chief accuser, Elizabeth Bentley. Brunini was said to have written Bentley's autobiography in return for a share of the profits. When U. S. Attorney Irving Saypol and his assistant, the now-infamous Roy Cohn, were confronted with these charges, they vehemently denied them, although FBI records later indicated that they had known about the relationship for months.

Although it appeared that Saypol and Cohn had lied, and that Remington had been indicted by a grand jury that was led by a foreman with a vested interest in putting him in jail, I could not be certain without examining the grand jury transcripts themselves. Since they were more than 40 years in the past at that point, I thought I could easily gain access and filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Justice Department in the summer of 1985.

When weeks passed without a response, I telephoned the Criminal Division at the DOJ to see what had become of my request. An official snidely informed me that I knew nothing about the law: Grand jury records were not covered by the Freedom of Information Act, but by the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which sealed them forever unless a federal judge ordered them declassified. "You'll never get those records," he gleefully told me.

Like many a person in trouble and without the money to hire a lawyer, I turned to the American Civil Liberties Union, which had helped other historians obtain classified government records. Not this time, however. Saying they were too busy to assist me, the ACLU forwarded my letter to the Public Citizen Litigation Group, which specialized in Freedom of Information Act lawsuits. I should hear from them soon, the ACLU assured me. Having been rejected by both Reagan's Justice Department and the ACLU, I worried that I might have to abandon the entire project.

On a Friday afternoon in November 1985, I received a call from Patti A. Goldman, a staff attorney with the Public Citizen Litigation Group, which offered to take my case and would represent me pro bono. That was the good news. The bad news quickly followed. Our chances of success were not good, Goldman said. There was no direct precedent we could rely on; grand jury records had never been released for historical purposes. Indeed, the last such request had been made by Alger Hiss, who had also been accused of espionage, and was summarily rejected by federal judge Richard Owen. Also important would be the position taken by the U.S. attorney in Manhattan. Essentially, he had three choices: He could join us in asking the judge to unseal the records, he could express no opinion or he could oppose us.

Who was that U.S. attorney and what did Goldman expect him to do, I asked? His name was Rudolph Giuliani, she told me, and he was an ambitious prosecutor primarily interested in jailing members of the Mafia and corrupt politicians, preferably if they were Democrats. He would almost certainly oppose us. But the effort was worth a try.

During the next few months, we compiled several volumes of historical and legal memoranda explaining the importance of the Remington case, and arguing that the public's right to know outweighed the need for continued secrecy. As expected, Giuliani opposed our petition and the government submitted its own briefs, to which we responded.

Finally, on Jan. 20, 1987, more than 14 months after this struggle began, the opposing lawyers met in the chambers of the Honorable Whitman Knapp, U.S. District Court judge in Manhattan.

Giuliani did not attend; representing him was his executive assistant, David W. Denton. He stated the case for the government: There was no authority for the court to release grand jury records for historical purposes and, on the rare occasions that such records were unsealed, it was only because the public had an immediate need to know the information they contained. If the court ruled otherwise, no one would dare testify in secret before a grand jury whose secrets might someday be revealed.

Patti Goldman emphasized the importance of resolving the questions related to the functioning of the grand jury system in the Remington case. Had the grand jury, which had been established to investigate Soviet penetration of American government, been turned into a vehicle designed to protect the personal interests of Brunini and his literary partner, Elizabeth Bentley? All this was just academic history, Denton argued, hardly worth the government's time. Judge Knapp bristled. "You have a very limited admiration for history," he told Denton. Admittedly, the general public might not be interested in past events, but historians would be. "The theory," Judge Knapp said, "is through them we all learn." Because of the undisputed historical significance of the Remington case, he found "a considerable public interest in disclosure and no interest in secrecy." Judge Knapp ordered Giuliani to release the Remington grand jury transcripts.

We had won, but Giuliani informed us that he planned to appeal Knapp's decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals, which meant that more time would pass before I obtained the records, assuming that the court affirmed Knapp's decision. Then Giuliani suddenly changed his mind and offered us a deal: He would not appeal Knapp's decision and would hand over the records — but only if I asked the judge to withdraw his decision from publication. In other words, Judge Knapp's decision would still stand, but would not appear in the casebooks used by attorneys.

A painful dilemma confronted me: I had begun this torturous process hoping to uncover what appeared to be the government's abuse of power in the Remington case. Now I was being invited to join in another cover-up — hiding Giuliani's embarrassing defeat and our victory, which also provided historians with a possible precedent to obtain other sealed grand jury records in controversial cases, like those perhaps of Alger Hiss or Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. My lawyer's advice was to accept the deal. We could publicize our victory, and inform the legal and historical communities of Judge Knapp's decision.

Feeling somewhat better, I complied, and by the summer of 1987 I had received about 500 pages of grand jury transcripts. They proved that Brunini, the foreman, had indeed been the driving force seeking Remington's indictment. The transcripts are filled with examples of improper tactics concerned only with the destruction of Remington's reputation. Second, comparing the grand jury testimony of witnesses like Elizabeth Bentley with their later trial testimony, I discovered discrepancies that often amounted to wholly different stories. It seemed probable that the government's witnesses had been skillfully prepared by Assistant U.S. Attorney Roy Cohn to change their stories to suit the government's case, and had themselves committed perjury.

Presumably, Giuliani, as the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, would be interested in such issues as the integrity of the grand jury process and the honesty of government witnesses at trial. But he seemed completely uninterested in the actual contents of the documents he was fighting to hide.

Furthermore, his behavior in 1987 suggested that he was less concerned with legal issues than he was with protecting his personal reputation from a minor defeat at the hands of an obscure academic and his lawyers. Vanity and self-promotion, not integrity, always came first. Giuliani's biographer, Michael D'Antonio, recently suggested on this site that like Donald Trump, Giuliani has a transactional nature and relentlessly seeks out opportunities he believes will benefit him. That nature was certainly on display in our case.

I doubt that Rudy Giuliani even remembers this modest legal incident, now lost in time and the chaos and clutter of an eventful life. In my view, it is suggestive of a man who cares little for the truth and will do anything to win.

Shares