Okay, humans, if we’re so smart, why do our backs hurt so much? Why do we cry? And menstruation, who thought that was a good idea?

Our existence on this planet is the product of chance, timing and a whole lot of evolutionary compromise. Our ability to speak and walk upright and gestate babies with big brains has meant sacrifice and discomfort, and this human condition we’ve created for ourselves is eternally humbling and idiosyncratic.

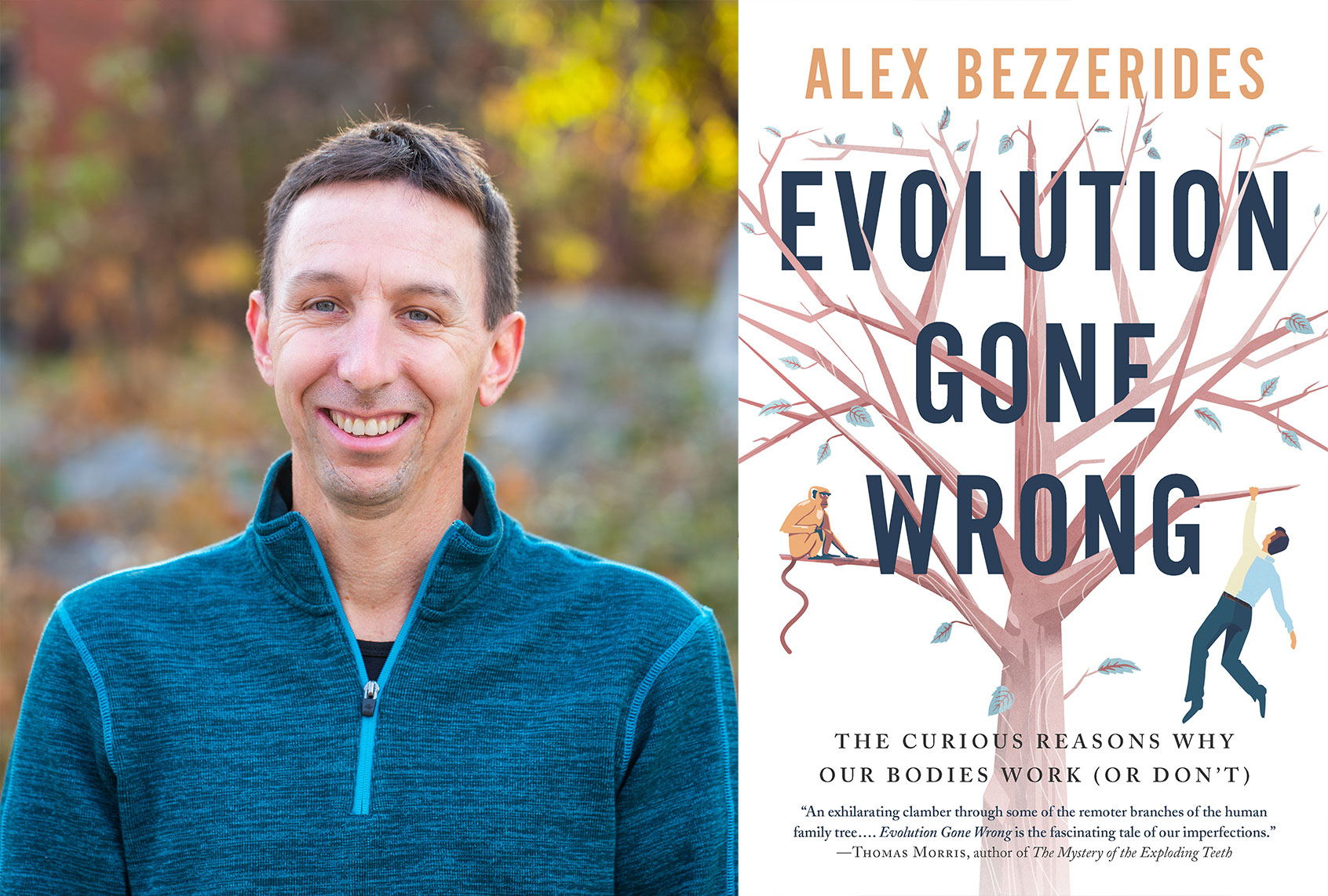

Alex Bezzerides knows it well. The Lewis-Clark State College biology professor is fascinated with the imperfect system that is the human body, and he explores and explains it adroitly in his fascinating, funny new book, “Evolution Gone Wrong: The curious Reasons Why Our Bodies Work (Or Don’t).” Salon spoke to the author recently about why we are the way we are, and the fallibility of the epiglottis.

I want to begin at the end of the book, because to me there is absolutely nothing stupider or more counterintuitive in the universe than our entire reproductive system. Menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth — they’re all ridiculous. Talk to me about this, Alex. Why do we have periods?

That was the hardest chapter for me to write because I went into it really not knowing the answer. That was unique, because most of the other chapters, I at least had an idea of what I was going to write about.

I started reading about the origins and evolution of menstruation, and it got complicated really quickly. I picked up this term, spontaneous decidualization, and I thought, “Oh, my gosh. How am I going to figure out how to translate this to the reader?”

What I came to learn is that the process evolved in a way as a defense for women against these really hyper-aggressive, invasive fetuses humans are. We think that human fetuses are that way because they have to feed this giant, growing, nourishing brain. The only way to do that is to burrow deep inside the woman. The degree of placentation in a human is much, much higher than it is in other mammals.

One idea for why menstruation evolved is that the woman had to start building up her uterine lining and building up this defense even before pregnancy. A big difference in mammals that experience menstruation is they start changing their lining before pregnancy, rather than in response to pregnancy. Then once that uterine lining has changed, if pregnancy doesn’t happen, it has to be sloughed. That’s one of the big ideas about why it evolved, is that it had to be there as a way to defend the mother against this burrowing human fetus. Kind of a crazy idea.

Just the volume of blood loss is astonishing. Every single month, the amount of blood loss that a woman goes through, it’s just an incredible figure. Every little time I get a teeny little cut and I lose a couple milliliters of blood, I think, “A woman can lose 30, 40, 50 milliliters. Some women, a 100 milliliters a month.” It’s just mind-boggling. You get to the end of this thing, and it’s just like, “My God. Why does anybody have kids? How does anybody have kids?” After seeing the whole thing, you feel like there should be like 40 people on earth rather than 7 billion. Like, no way. But it’s happened 7 billion times. That’s of course for the people that are currently alive. It just doesn’t seem possible.

You make a very interesting case that that our big brains are not necessarily the sole metric of our intelligence. From an evolutionary perspective, maybe this isn’t the end game, that the smarter we get, the bigger our brains are going to get, the bigger our heads are going to get, and then no one gets born anymore. Talk to me about what evolution might look like.

I think the other piece of the puzzle that has to be talked about any time you talk about the human body and the direction it’s gone is the bipedalism aspect. I think that when humans went up on two feet, and it obviously took millions of years for that transition to really fully occur, it just changed so many things about the shape and nature of the body.

One of the things for women is the change of the nature of the birth canal. One of my favorite scientists, that I lean on a lot in the book, is Dartmouth Professor Jeremy DeSilva. He is the foot, and skeletal, and paleoanthropology guy. He and this group found that, even before the brain swelled up to its current huge, ridiculous size, birth was a tight process for hominins and for early ancestors as soon as they basically went bipedal.

That right there set us on this path that made birth difficult. Then, getting into the skeletal chapters, that made our life difficult for our ankles, our feet, our arches, our knees, all these different things. Obviously there are wonderful things that come out of it. There’s a whole other book to be written about how amazing evolution has been for us, and our incredible hands and our incredible minds. I thought it was more interesting to write the the darker side of the coin, about all the ways that it’s also been difficult.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

This gets back to the overarching story of this book, the trade-offs of evolution.

I thought of the word “trade-offs” throughout the entire book. Like in the throat chapter when I talk about choking and snoring, all these things are trade-offs.

One of my favorite examples of that is where we have this incredible human feature of being able to form words, and speak, and change our vocal production in ways that other animals can’t do. But the trade-off of that is that the larynx had to get lower down deep into the throat, and you lost this fail-safe that kept us from being susceptible to choking.

I think about that all the time. Just last night I took a little drink, and my epiglottis didn’t quite do its job. I splashed a little water down into my trachea. You kind of sputter for a second. That happens all the time. It’s just this great evidence of an evolutionary trade-off in humans. But then the benefit is that I get to talk to you, which is something other animals don’t get to do.

We get to talk to each other, but then we also had to cut up our kids’ grapes for a really long time.

And my wife has to elbow me to stop me from snoring.

And the reason that we get back pain or the reason that our shoes don’t fit is because we learned to walk upright. Walking upright makes you really tired.

It’s exhausting. I think about it when I get up in the morning now and I have a little back pain. I just curse the whole curve of my spine, and all the things that are necessary for me to work my way around upright.

Thing that I really enjoyed about this book is that I kept the topics universal and broad enough that you can’t talk to anybody that didn’t have a tough birth experience, or didn’t have back pain, or didn’t have three wisdom teeth pulled and one of them was kind of a mess, or something. I find that it relates to everybody, and that’s been a really fun.

I had adult orthodontia, but I never made that connection of, “Why don’t my stupid teeth fit in my stupid mouth?” Some of these evolutionary problems are also because we’re living longer. We’ve not yet built our bodies to endure for as long as they do, so our backs give out, and our ACLs tear, and our eyesight starts to go.

There are definitely some features in the book that are exacerbated by age. There’s no question about that. I tried to focus on things that can fall apart at any point. I think teeth not fitting and eyesight going bad, those are things that can certainly happen at a young age, but it’s not helped by the fact that we’re all living to be 70, 80, 90, 100, whatever.

I love the part of the book about blinking, and why we blink as opposed to licking our eyeballs, which would be disgusting. When we talk about crying, why do we cry when we’re sad, or we’re happy, or we’re overwhelmed?

There’s this connection between our brain and our anatomy that we’re just beginning to understand. One of them is this endocrine hormonal balance with things like crying. We have a great understanding of what tears are there for — to keep our eyes moist, and it’s necessary. But then these things happen that are tied to our emotions that I don’t think we do have as good an understanding of.

The short answer is that those emotional tears have hormones in them (unlike the other types of tears) and one working hypothesis is that those hormones (like prolactin and oxytocin) help to soothe the body. More research is clearly still needed. I like to imagine a whole room of people sitting around watching “The Notebook” as researchers take measurements of all their baseline physiology. I cry at the drop of a hat (for example I cried during an episode of “Kim’s Convenience” the other day), so I’ll be keeping a wet eye out for any future crying research.

What were the things in the book that surprised you the most or made you take a step back?

The reproductive section, for me. There were a lot of things that caught me off guard with the fertility chapter. I just didn’t realize how many things humans are up against when it comes to fertility. People mostly think about fertility issues as a modern problem. Everybody’s waiting longer to have kids, and there are all these modern dilemmas related to fertility, and pollution, and incorporation of things in your body that weren’t there generations ago.

When I started reading about fertility, you realize that fertility issues have been a thing for as long as people have been around and as people have written about it. There’s this whole historical evolutionary perspective of it. A big part of it is the historical mating systems that humans had and the sperm competition that was set up, and how males had to produce overwhelming amounts of sperm in order to compete with other males.

But then females couldn’t have an egg fertilized by multiple sperm, so their bodies evolved these defenses to prevent polyspermy, where two sneak in and fertilize an egg. You end up with this reproductive back and forth, just to get over this hurdle of creating a new life. That was something that I didn’t really know anything about going into it, the whole evolutionary historical perspective of fertility difficulties. That was really eye-opening.

I remember being at a zoo one time, watching some ungulate when she was giving birth. I didn’t grow up on a farm or anything, so I hadn’t seen cows being born, or a horse being born, or anything. That was the first time I watched a big mammal being born.

She just gave birth, licked the thing, and then it hopped up shortly thereafter and wobbled around. I was like, “Seriously? That’s it? That’s ridiculous compared to what we do.” It’s like days in the hospital and weeks in bed, and then you have to hold a little horrible thing for like a year before it can even do anything. What? [laughs]

You can’t leave it around grapes. It’s ridiculous.

Ridiculous.

We have evolved so that other people have to be involved in that process, and we can’t do it alone. This feels really important for us to remember as a species, that we are designed to bring children into the world together. Because it’s a messy, incredibly painful, incredibly dangerous process.

It is. I don’t think people realize just how many women died in the process and still die in the process. Before the advent of antibiotics, it was an incredible number of women that died during childbirth. In parts of the world where they don’t have access to antibiotics, because of the incredible trauma, infections are still a huge problem. Many, many women do still die in childbirth.

It’s a neat feature of human society and human cultural development, that birth has become such a group and a family process. It almost has to extend beyond birth, too, as an important thing about why human infants are born so helpless, because it’s another unique thing about human birth.

This whole idea that Holly Dunsworth has written a lot about, it’s because the classic explanation is that they have to come out early or then there’s compromise between women’s mobility and the shape of their hips, and the size of the baby. The Obstetrical Dilemma just really took off. There’s not much evidence for it, and she’s come up with this new idea that there is a lot of evidence for, that it’s all driven by metabolism. In fact, the baby gets to the point inside the mother where she can no longer nurture its metabolic needs as it grows, and its brain gets so big, the only way to continue to nurture it is outside the mother, and then it’s born totally helpless. Not only do you have this birth process where the mother needs a lot of help just to get through the birth, but then, even after that, a lot of help is still needed because there’s this super, super altricial infant on her hands that you need a lot of help to be taking care of.

Was there something in the book that really made you marvel? Every part of being human and walking around in these imperfect, breakable systems is kind of remarkable, but was there something in particular that really just takes your breath away?

I think the brain is, in a sense, there, but I’m going to go a different direction. Toward the end of the book, I started reading about the human hand a lot. Obviously I knew primates have different hands, and opposable thumbs were a different thing. But I didn’t appreciate how different the human hand was from other primate hands, and what that allows us to do.

I think about that all the time now when I see somebody playing a musical instrument, or doing some incredibly little dexterous craft that no other animal on earth could do. I’ve started to think of the human hand as as integral to humanness as the brain.

It’s also really interesting to me that it came around first. That once we became bipedal our hands freed up, and we went down this path that has allowed us to just create a whole world with our hands. That all happened before our brains kind of exploded. It’s a necessary step that the brain took off afterwards, and the way to really effectively use that hand.