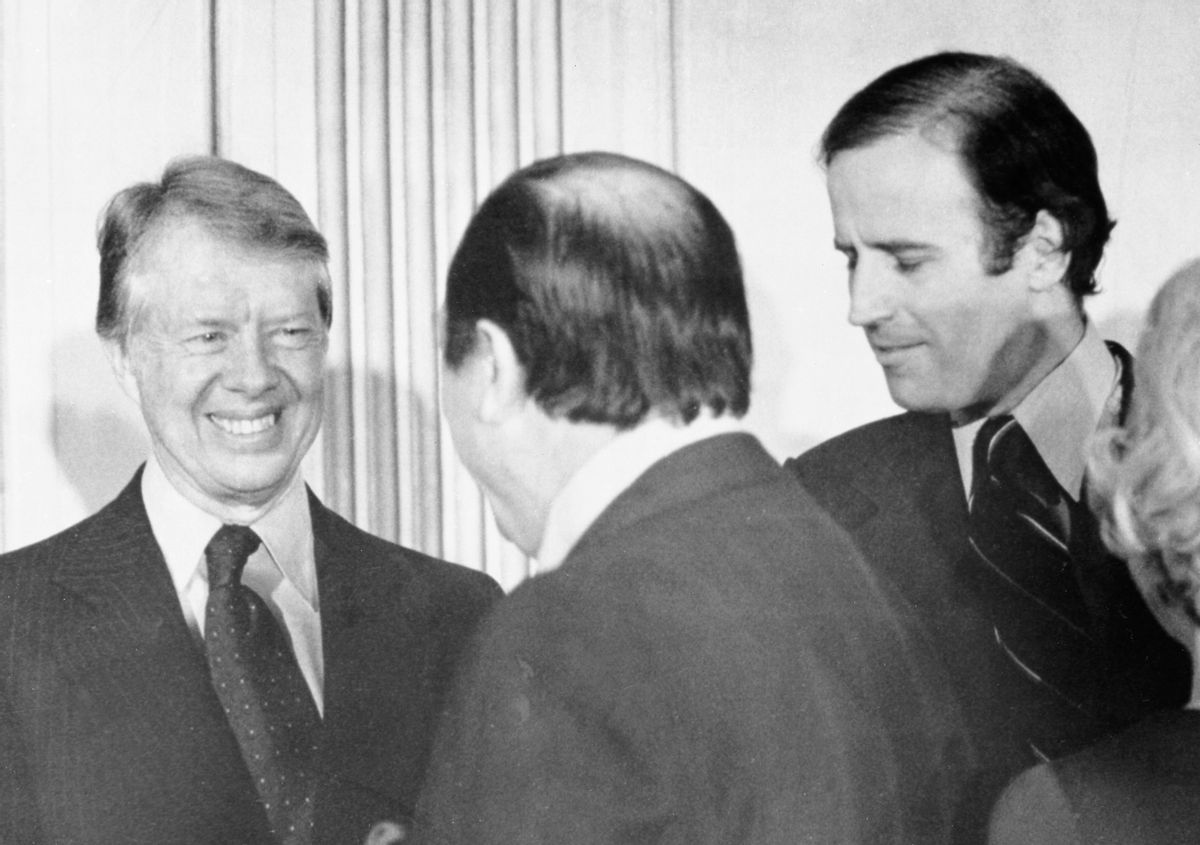

Gasoline shortages erupted a few weeks across the Southeast and parts of the Eastern seaboard, reportedly caused by a cyberattack committed against the Colonial Pipeline stretching from Texas to New York. The shortfalls have spurred some of President Biden's political opponents to invoke comparisons to Jimmy Carter, who suffered politically while long lines of motorists tried to fill up their gas tanks in the late 1970s, and als struggled with several other major economic issues.

On May 7, ostensibly referring to rising fears of inflation as the economy recovers from the coronavirus pandemic, Donald Trump Jr. tweeted that "Biden isn't the next FDR he's the next Jimmy Carter," as one of Carter's main domestic battles in office was also against rising prices. On May 11, when lines at gas stations began to emerge in the wake of the pipeline hack, Trump Jr. retweeted himself with the added comment "As I was saying …" The next day, his father, the former president, put out a statement claiming that the comparison was unfair — to Carter. "Joe Biden has had the worst start of any president in United States history," said the senior Trump, even worse than the president from Georgia.

Perhaps it's understandable that the Trumps might want to link Biden to Carter, who left office in 1981 in shame, having been thoroughly defeated in his bid for re-election by Ronald Reagan. But the comparison likely won't stand for long, because our current situation bears little resemblance to the political morass of the late 1970s that doomed Carter's quest for a second term in office.

Jimmy Carter wasn't even the first president in the 1970s to experience gasoline shortages on his watch. That honor belongs to Richard Nixon: In October 1973, when the United States was caught covertly supporting Israel in its war against Egypt over control of the Sinai Peninsula, the nations of OPEC (the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) instituted gradual cutbacks in exports to the U.S. as punishment. As the embargo intensified over the following months, lines emerged at gas stations across the country, and angry motorists got into verbal arguments and fistfights as they waited, sometimes for hours, to fill their tanks. In November, Nixon proposed a domestic energy production program called Project Independence, but was too consumed by the emerging Watergate scandal to really focus on it. Consumer sentiment soured further as the months of uncertainty dragged on. But eventually, Saudi Arabia worried that its relations with the U.S. might suffer permanent harm if the embargo went on for too long, and called it off the following spring.

But in the meantime, the embargo had done lasting damage to the American psyche. It was the first time in the post-World War II period of U.S. history that Americans faced the distinct possibility that their perpetually rising standard of living might not go on forever. The OPEC nations had successfully used oil as a tool of punishment against America for its foreign policy. What would stop them from doing it again?

After Nixon's resignation, Gerald Ford signed into law the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, which created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and also established fuel economy standards that automobile manufacturers would have to meet. But Carter, who narrowly defeated Ford in the 1976 election, went much further in addressing the energy issue. Carter saw American dependence on foreign oil as an existential threat to the nation's future but also as a moral failing, calling the energy challenge the "moral equivalent of war" in a major April 1977 speech. For Carter, in the decades following the shared sacrifices of World War II, Americans had become too selfish, greedy, individualistic and wasteful. In order to obviate the possibility of future energy crises, Americans needed not just to increase domestic energy production, but to excavate and restore the sense of shared responsibility from three decades before. Carter convinced Congress to create a federal Department of Energy that would spearhead national conservation initiatives, and spoke repeatedly of the need to rethink fundamental assumptions about the American standard of living.

Unsurprisingly, many Americans opposed this paradigm. In the past few decades, they had seen the American government defeat fascism, provide a bulwark against communism, address serious civil rights challenges and pass laws to clean up the environment. It seemed like a much smaller challenge for the government to figure out how to let Americans drive to work and take their kids to soccer practice without the looming threat of existential energy shortages. But many Americans also followed Carter's directions, sometimes with a bit of grumbling — insulating their homes to diminish the need to use energy on heating and cooling, combining trips out and carpooling.

But in 1978 and 1979, Carter's troubles compounded. A revolution in Iran against the ruling shah destabilized the country and brought the hardline anti-American Ayatollah Khomeini to power. Instability in that key oil-producing nation rippled outward, bringing back the lines at American gas stations from a few years before. From the perspective of many Americans, Carter had promised them that acts of individual sacrifice, along with accepting a diminished standard of living, would reap rewards in the form of energy security. Now the shortages were back anyway. In another act of national humiliation, the new Iranian regime took 52 American hostages from the U.S. embassy in Tehran. In a failed April 1980 rescue attempt, an American military helicopter crashed in a desert sandstorm, killing eight American servicemen. To many American voters, Carter seemed unable to handle any challenge laid before him. In truth, in many ways the problems facing Carter were likely out of the control of any American president, but his lecturing tone certainly didn't help matters. Voters punished Carter in fall 1980 by handing Ronald Reagan 44 states and 489 electoral votes.

That situation bears little resemblance to the one Joe Biden now faces. The gas shortages of May 2021 were caused not by cutbacks by foreign nations, but a cyberattack against a domestic pipeline. The crisis appears to be resolving itself now that the system is back online. Panic buying among consumers, which exacerbated the problem, won't go on forever either. Just as toilet paper, paper towels and sanitizer returned to store shelves after the first days of pandemic panic buying, so too will gasoline return to our local stations. Gas prices will likely settle into a price somewhat higher than they were for the past year, but that's an inevitable consequence of businesses, schools and entertainment venues opening up again. Few Americans would likely accept an indefinite extension of the necessary but dispiriting lockdowns that kept gas prices exceptionally low for the past year. Furthermore, Biden's tone during his first few months in office has lacked Carter's pessimism; in fact, Biden has often spoken confidently about the possible American resurgence that could take place as the country claws its way out of the pandemic.

Of course, there is still much uncertainty ahead. Supply chains disrupted for more than a year by the virus will take time to be restored to full operation, and new variants of the virus could continue to pose a threat to public health. But jobs are beginning to return, and the explosive demand for homes means that the construction industry, a major driver of economic vitality, could have an especially bright future. One of Biden's major challenges will be to make sure that future American jobs are good, well-paying, secure ones, and one way to help make this possible would be to raise the federal minimum wage — but since Trump's GOP isn't exactly eager to embrace this, they have little room to complain. Inflation will also be a concern in the near term, but if the Federal Reserve raises interest rates from their current (and unsustainable) near-zero level as the economy recovers, it may not be a major long-term problem.

It's understandable that Trump and his son might want to link their political foe to the presidency that seemed to define American decline. But it won't work: Joe Biden isn't Jimmy Carter, and these most definitely aren't the 1970s.

Shares