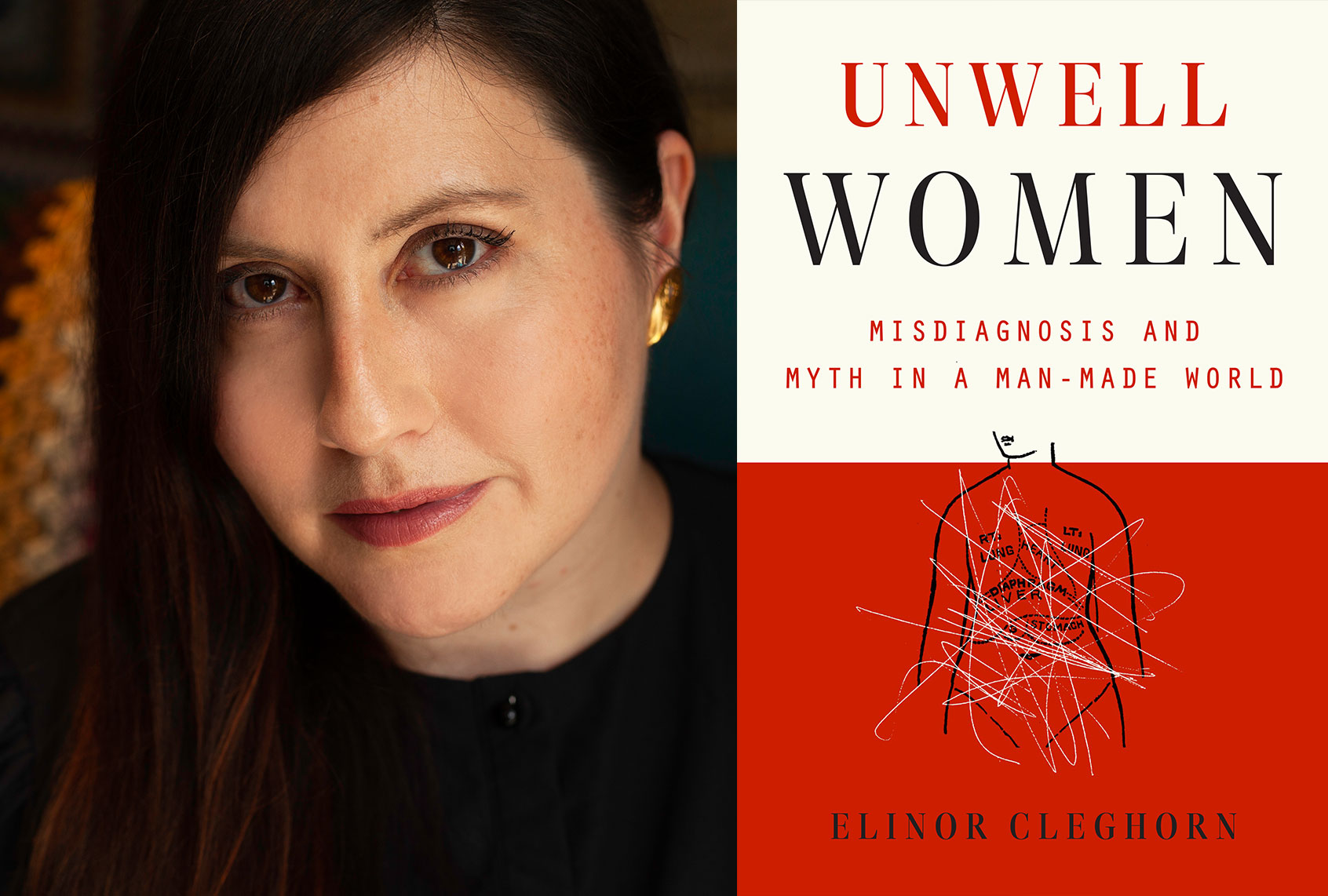

Our society pushes some weird narratives about women. Women are delicate flowers who need to be protected, we’re told. But we’re also disgusting animals who bleed and leak milk and get hair in places that upsets people. We’re amazing. We’re gross. We’re powerful. We’re weak. It’s definitely all in our heads. We are, as Elinor Cleghorn notes in her fascinating new book “Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World,” considered the caretakers of humanity — but men are the authorities, even of our own bodies.

At once an enraging, meticulous history and an intimate personal story, “Unwell Women” is an exploration of women’s unique and (often fatally) misunderstood treatment in medicine, and a call to change our deeply engrained assumptions about healthcare.

Salon spoke to the English author via Zoom recently about hysteria, lobotomies, and why confronting the past is an essential part of a healthier future for women. As always, this interview has been condensed and edited for print.

The book is very personal, and that gets to a big part of what drives this story. What made you write this?

The origin of this book was my diagnosis with systemic lupus erythematosus, which is an autoimmune disease and the most common form of lupus. It affects 90% more women than men globally.

I was diagnosed with it ten years ago, when I was thirty. My second son was nine weeks old, and we’d just been through a really difficult pregnancy because he had a heart condition that was caused by my own immune system mounting an attack against his heart while I was pregnant. After he was born, I developed a heart condition of my own that was really baffling to my doctors, and I ended up hospitalized. I had fluid around my heart, which is called pericarditis. They explored lots of different options, but none of the doctors looked at the notes and put together the puzzle pieces of what had happened during the pregnancy and what was now happening to me these few weeks later.

After having lots of tests, lots of blood work, ultrasounds, MRIs, and being in the hospital for about ten days, a rheumatologist visited the cardiac ward where I was being cared for, and he looked over my notes and ordered some counts of my rheumatoid factor to see if I was inflamed. He said, “Look, I think she has this disease, and this is what caused the issues with her baby, and this is what is causing the issue with her now.”

So, I received this diagnosis, was referred to a specialist clinic in London, and from then on was one of the many million women across the world that have this disease. I entered into the health system as a chronic illness patient.

In those early days, there were very few explanations as to why lupus affects the people it does. Nobody knows exactly what causes it. Nobody knows whether it’s necessarily genetic. Not a great deal is fully understood yet about why it affects so many more women than men, and so every time I asked a question, I felt like I just had no answers. All I was really being told was that I could be medicated to manage my symptoms. So I started researching it.

I was a researcher at the time, doing my PhD. I did my PhD in cultural studies and humanities, and I was working on feminist histories. Alongside doing that work, I started searching for case studies of lupus. I kept finding these women in historical cases whose situations and life stories felt so familiar to my own. There were usually lots of complex symptoms, predominately joint pain, but also organ involvement. And there were lots of misdiagnoses — quite often with psychiatric issues, and then finally either a diagnosis or sadly often death, followed by an autopsy, and then a posthumous diagnosis. It baffled me. It fascinated and infuriated me all at once that more than a century later, I was still a patient with this, and my care was still being thwarted by these mysteries.

I thought, “There’s something in this.” I had the impulse to research. I just started mining through some of the histories of other chronic diseases that were coming up in association with the rise of the wellness industry. These narratives around women not being listened to, women being misdiagnosed, women being in pain and being told that they were anxious or stressed. I just thought, “There’s a story to be told, and I want to know why this is happening.”

Let’s talk about the minimization of women’s pain, because that’s the start of it. There’s the idea that the things that women feel can’t be real. Why is our pain not taken as seriously as male pain?

I think that there are two really distinct reasons why our pain isn’t taken as seriously as male pain. One is the minimization, which I think is rooted historically in the idea that in many ways women’s bodies exist in order to feel pain. The primary purpose of the woman historically in society was to bear and raise children. If we go back to ancient Greece and to the classical so-called fathers of modern medicine, like the Hippocratic writers, we see very much that the understanding of the human body in terms of gender is that a man is this idealized creation. The woman is a failed version of that idealized creation, but she also has a very particular purpose, which is marriage and motherhood.

Because women’s purpose is ordained to entail pain, there’s been a historic and cultural normalization and minimization of women being in pain. We feel so much pain anyway because of the way that our bodies work — because of menstruation, because of the lack of understanding that comes through those blind spots of privilege in male bodies. What’s happened over the centuries is that women’s pain has been really normalized.

There’s a great quote from one of the Charles Meigs, who was an obstetrician in the 19th century. He’s giving a lecture to his students about what a woman is. He says something along the lines of, she’s a gestational and a painful creature. This is women’s lot in life, to feel pain. It’s part of what grants us our humanity. I think a lot of the minimization of women’s pain has come from this idea that we exist to feel it.

I think on the other hand, as well as minimization and normalization, historically there’s been an over pathologization of the roots of where women’s pain comes from because the male body is the model patient, and the woman is other. She’s a subgroup. She’s marginalized. I think there’s been a real tendency to pathologize where women’s pain comes from, so male pain historically has been legitimized as coming from disease, malfunctioning bodies, something organic, something that’s wrong that can be put right. Because there’s that lack of understanding and also that normalization, if a woman says that there’s pain in her body, it must come from her mind. Somehow she must be creating it herself rather than it being something that she has no control over because it’s happening in her body.

I think these ideas, they’re still expressed. They’re still ingrained in our medical knowledge today. We have moved on exponentially over the centuries in our attitudes toward gender and our understanding what a human body is, but because those attitudes are so ingrained, they’ve shaped a lot of the understanding of diseases from a clinical perspective. Statistically, it’s been shown that if a woman presents with chronic pain that doesn’t have an immediately diagnostic cause, she’s more likely to be seen as having a mental health condition than to be referred for further tests. She’s much more likely to be dismissed with a recommendation of a sedative or an antidepressant medicine than an analgesic or opioid pain medication, which men would be offered.

What we haven’t done, I don’t think, is looked at those myths and asked, “Well okay, how has this actually interrupted and steered how we understand women’s health?” Those myths perpetuate because we just haven’t spent enough money, dedicated enough research, given enough visibility to representing women in knowledge in the contemporary era of medicine.

There’s a phrase that you use, “the necessity and inevitability of pain.” That’s the lot of being a woman, that if you do complain, you’re literally hysterical. You cite a figure about lobotomies.

The figure is astonishing. Something like estimated 75% of all cases of prefrontal lobotomy in the 1940s and ’50s were women, and many of those women were older. What we would call middle age was then considered “older” women. As well as the minimization and dismissal of women’s pain, I think there has also been a real impulse in male-dominated medicine to solve what are essentially social problems suffered by women in their lives by really barbaric surgical interventions. This happened in the 19th century with some of the supposed gynecological cures, which involved removing women’s ovaries for example or performing clitoridectomies on younger women as a way of making their bodies neat, and making them behave, and curbing this unruliness that was believed to be inherent in the female body and mind.

I think the lobotomy was seen as a fix for a problem that was both social and medical at once. Medicine had created this idea that women, if they’re in pain, if they’re suffering, then they’re crazy. Also, there was this idea that there was a cure. There was a sense that if you butchered the body then you could somehow cure the mind.

I remember reading the book by Freeman and Watts, the American neurologists who really popularized the prefrontal lobotomy in the 1940s. They wrote a book about the success of what they call the psychosurgery, and they talked about lots of case studies. The language that’s used around the women who went through this horrendous procedure was so infantilizing and dehumanizing. They would describe women as being shrewish and highly strung and shrill and, indeed, hysterical before they underwent the procedure, and then talk about them afterwards being returned to an almost childlike state of blissful ignorance.

One husband had apparently told Freeman and Watts after his wife had gone through this procedure that she was full of, and I quote, “don’t give a damn-ness.” Of course, what they’ve done is literally severed the part of her brain that can make meaning of her life. To use this horrible, flippant phrase when they’ve severed her ability to make meaning of her life and her thoughts is horrific. I think it would hand down that cultural moment that’s full of stigma around mental illness.

When you’re talking about that phrase, “neat,” I think of the boom of labiaplasty and cosmetic surgery around our bodies, where it’s all about being as tidy and small and childlike as possible. It all comes back again to this idealized image of what a woman’s body is, and it’s always in context to what the male body is and what the male mind is simultaneously.

Plastic surgery and chemical manipulations for bodies and faces has become so normalized, especially over the last two to three years, in much younger women. There’s something always about the female body in its natural state is seen to be unruly, and messy, and un-tameable, and uncontrollable. The fact that you bleed has to be hidden, the fact that you hurt has to be hidden. The mess, the dirt, the humanity is gone.

Yeah, body hair. You have to be infantilized and made smaller than you are, but also to not pollute or contaminate anything. This idea about contamination, pollution and contagion has haunted women’s bodies throughout history. I think it’s probably rooted in menstruation, but it’s this idea that women just need to be contained, that women’s basic humanness always needs to be parceled away, hidden.

I don’t quite know what the controversy has been like in the UK, but here in the US, this myth that vaccinated women can somehow contaminate unvaccinated women is wild. It’s exactly what you’re talking about, and it’s happening.

What is so shocking about that is the acceptability of the myth that women are contagious in the first place, the roots of why that misinformation captures and sticks. It’s already somehow there in the cultural consciousness that women are these contagious beings and that we will infect everyone; we’ll get our mess everywhere. It’s already there, so it’s perfectly set up to be believed , which is horrifying.

I think similarly one of the other real fears around the vaccine that seems to have spread quickly is about women suddenly bleeding, suddenly menstruating a lot, or possibly even miscarrying after they’ve had the vaccine. I think there is evidence to show that a very small percentage of women may have a little bit of menstrual interruption after having the vaccine. When you look at it, being unwell can affect your cycle. Your immune system does have an effect on your cycle. This isn’t unusual. This is to be expected, but the way this has been inflamed into “Women will suddenly just bleed on the floor of the vaccination clinic” is again because we’re just predisposed to believe such things.

You talk about the ways in which women’s health is so intersectional with race and class and money. It’s a hard thing for us to look at, but you do go head on, particularly into the ways in which the reproductive rights movement has its roots in eugenics.

These stories are really hard to hear as a feminist, especially as a white woman doing feminist work because reproductive rights, reproductive justice, birth control, are all associated with real progress and liberation for women. For example, the invention of the contraceptive pill is often cited as the most liberating moment in womankind in our history. Contraception was very hard won in both the UK and the US, and globally of course, and it still is. And it’s always a precarious right.

But it has a very complicated history of its conception, invention and realization as something that everyone can take that’s wrapped up in the exploitation and abuse of women of color, particularly of Latina women who were used in the 1950s as experimental subjects for trials of the combined contraceptive pill in Puerto Rico. Because of the constant ban on contraception distribution and research gathering in the States, those who were developing the pill knew that the FDA wouldn’t approve it unless it was tested on a large representation or a pool of women.

Margaret Sanger, who is the pioneer of birth control and the founder of the early formed Planned Parenthood, had always been searching for a very democratic contraception. She was a woman very interested in the burden of multiple child bearing, especially working class women. But she also carried very eugenic beliefs about who should be allowed to have children, what kind of future America should have, and what role family limitation through motherhood should play with that. She was involved in the early development of the pill, and there was an awful quote exchanged in a letter. Margaret Sanger didn’t say this, but they needed, and I quote, “a cage of ovulating females,” in order to test the pill because they knew this was the only way it could get past the FDA.

Trials were organized in Puerto Rico where contraception wasn’t illegal, unlike in the mainland US where it was. The issue around these trials was that the women were chosen specifically so that they may have had poor literacy or they may have been in a position where they had multiple children. And, they were being offered by nurses, community workers, and social workers involved in this project, something that was free that was touted as being very safe that would mean that they wouldn’t get pregnant. But they weren’t informed of the possible side effects.

The hormonal levels of estrogen especially were so high in these early pill models, and the women were not able to give informed consent. They did not expressly understand they were part of a clinical trial in the first place. One of the developers of the pill actually said that they had, and I quote, “emotional superactivity” of Puerto Rican women. If they did complain of side effects, and they did, it was explained away to either enforce racist beliefs that Puerto Rican women, that Latina women are overly emotional. Again, we have this resurgence and a real compression of this awful mythology around women’s pain being in their minds and also this is compounded by the racist deepening of that false idea.

The genesis of the pill is rooted in an exploitative medical experiment really, but it’s also rooted in a eugenic idea about who should be allowed to have a family, who should be allowed to be a mother. At the time, of course, there was a lot of economic difficulty following the war. In the UK as well, there were arguments that were circulating before and after the war that were very similar. Our pioneer of birth control, Marie Stopes, similarly had really entrenched eugenic beliefs, and she was extremely ableist and extremely racist. She would really champion birth control as something that would improve the lives of white women. She was a champion of working class women again, but within that she also had a white supremacist belief in this vision of the UK, a fit, white one that was free of — they used terms like “mental defects.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

It’s really hard to hear, but I think that it’s important to look at the real history, and think always about how we can hold the two things at once. We can look at the pioneers and the progress, but we also really have to think about who that progress was made at the expense of. It is difficult, but I think it’s really important.

After this pandemic year that is in many ways ten steps backwards for our health and social progress, what are the lessons of this particular crisis?

COVID has really illuminated questions of emotional labor, and caregiving, and the impact that has on women’s mental and physical health. At times of health crisis, women will be and always have been historically, the caregivers, the ones who have to sacrifice their well being in order to keep society rolling along.

I think it’s also illuminated questions around what we do and don’t know about determinants of health. It’s brought really into public consciousness questions like the under-representation of women and minority bodies in clinical trials, for example around the vaccine. It’s also bringing to light issues around the systemic and social basis of issues like vaccine hesitancy. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, at least in the UK, some of the most vaccine hesitant groups are women of color. It’s not a coincidence when women of color come from histories where they have been exploited and abused, especially by public health interventions. We’ve got now a way to structure these conversations, rather than just saying, “We know what’s happened. Somebody just pay attention.”