American democracy is in danger, and American journalism needs to respond with more than slogans.

Editorials are a good start — and the Boston Globe has now set the bar awfully damn high.

But the mightiest weapon in the journalistic arsenal isn't opinion columns. It's relentless news coverage.

Journalists have the unique ability to ask questions on behalf of the public, demand answers, assess truthfulness, decry stonewalling — and do it all again the next day.

To rescue and revive democracy, news organizations don't need to "take sides" with one party or another, and they don't need to publish articles full of opinions.

What the top editors in our top newsroom must do, however, is set the agenda. They need to decide what is newsworthy, and then bring their resources to bear accordingly.

That's the true power of the press.

And those editors should start with an easy one — by relentlessly covering the Justice Department's recent outrageous seizures of reporters' communication records. That means news stories every day until the public is able to fully understand how they were authorized and by whom, how they were allowed to proceed and what will prevent similar occurrences in the future.

Assaults on freedom of the press aren't "inside baseball." These are the front lines. This is a huge story. As David Boardman, dean of the journalism school at Temple University, tweeted:

The formerly secret subpoenas were for records from reporters at the New York Times, the Washington Post and CNN, in order to identify their confidential sources. Two of the subpoenas were accompanied by outrageous gag orders. (Gag orders on news organizations!)

Their overdue public disclosure by the Justice Department in recent weeks made major headlines and spawned a number of angry opinion pieces.

But with the notable exception of the Times, there's been relatively little news coverage since then. (On Thursday night, the Times continued its streak with a barnburner report that Trump's DOJ had similarly subpoenaed communications records of Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee.)

What's particularly missing — even from the Times coverage — is the application of pressure on the current Justice Department leadership to fully explain what happened, when, why and how. That should be the drumbeat, every day.

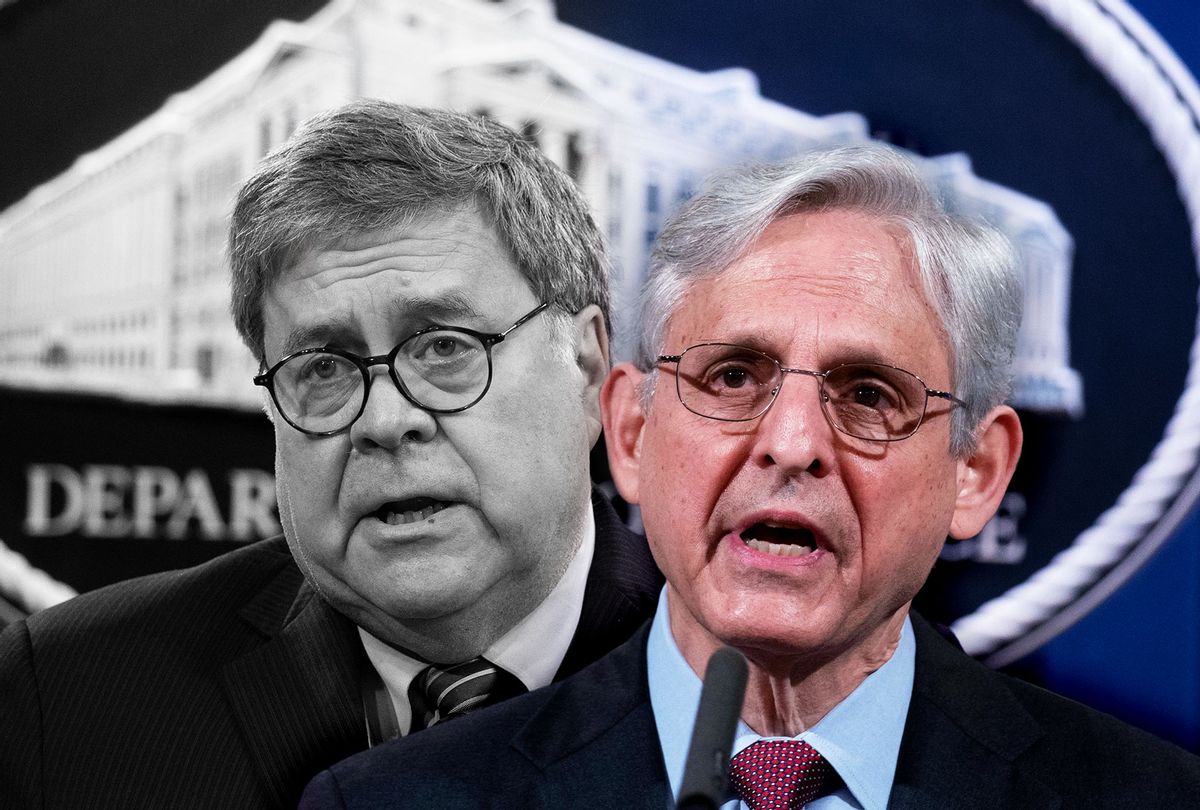

Although the various leak investigations originated during the Trump administration, they extended well into Biden's. A huge element of this story is why those investigations weren't immediately abandoned and condemned — and why the Justice Department under Merrick Garland won't come clean about what happened.

Some of the opinion pieces were powerful, particularly the one from the normally invisible Washington Post publisher, Fred Ryan. He appropriately pointed out that "the Biden Justice Department not only allowed these disturbing intrusions to continue — it intensified the government's attack on First Amendment rights before finally backing down in the face of reporting about its conduct."

In fact, it was the Biden administration that imposed the gag order on the New York Times's lawyer, preventing him from disclosing the government's efforts to newsroom leaders or the four reporters whose email logs were at issue. [UPDATE June 13, 12:30 p.m.: Technically, the gag order was imposed by a federal magistrate judge, responding to an application from the Justice Department. The March gag order amended a January order that had fully gagged Google from talking to anyone about the records request. The March order allowed Google to tell the Times's lawyer, but imposed a gag on him as well.]

"This escalation, on Biden's watch, represents an unprecedented assault on American news organizations and their efforts to inform the public about government wrongdoing," Ryan wrote.

The Justice Department on June 5 announced that it would no longer use subpoenas or other legal methods to obtain information from journalists about their sources, eliciting some new headlines.

But that should not have placated anyone in the news business. What it should have prompted is a slew of additional questions about how this new policy would be applied in an accountable fashion.

As Anna Diakun and Trevor Timm wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review, the new policy is "a significant improvement to the DOJ's previous approach. Still, there are questions to be answered. When will the DOJ officially update its news-media guidelines to reflect this change? And as the Times noted, the DOJ's statement appears to leave some 'wiggle room' surrounding the circumstances in which the policy applies, limiting it to when journalists are 'doing their jobs.' What exactly does this mean?"

Their final, critical question: Who will the Justice Department consider a member of the news media?

None of the news reports I saw about the policy shift showed anything like the appropriate skepticism. For that, you had to watch television interviews with some of the reporters who were directly targeted.

On CBS Now, for instance, Times reporter Matt Apuzzo made the crucial point that there's no reason to take the Justice Department at its word until it fully explains itself. "First we have to understand what happened. … How did it happen? Why did it happen?"

"This is becoming a bipartisan pattern," Apuzzo said.

Journalism groups are justifiably concerned. Bruce D. Brown, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said in a statement that "serious unanswered questions remain about what happened in each of these cases."

And by coincidence, the esteemed free-press advocate Joel Simon announced this week that he will step down after 15 years as executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. He told the Times: "Governments are increasingly taking aggressive action toward journalists, and there are very few consequences."

Another weird one

In addition to the three demands for records in leak investigations, we also learned in the last few days about a Biden-era demand from the FBI that deserves more coverage. The FBI issued a subpoena to USA Today, demanding it hand over identifying information about readers who had accessed a particular story online during a 35-minute window.

The request related to a Feb. 2 article about the shooting death of two FBI agents while serving a warrant in a child exploitation case in Florida. The 35-minute window in question was more than 12 hours after the shooter had killed himself inside his barricaded apartment.

The request was bizarre and inexplicable, and should have been blocked by superiors. Instead, it was only withdrawn "after investigators found the person through other means, according to a notice the Justice Department sent to USA TODAY's attorneys Saturday."

How could that have happened?

Questions for the New York Times and CNN, too

Some of the ideally relentless news coverage would also involve questions for the news executives who received subpoenas.

Why did New York Times lawyer David McCraw honor such an obviously absurd gag order? (The order, imposed in March, related to records that were four years old, evidently as part of a fishing expedition aimed to show that former FBI director James Comey disclosed a "secret" document that was most likely a hoax. I am not making that up.)

Why, once McCraw was allowed to discuss the request with Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger and CEO Meredith Kopit Levien, did they honor the gag order? Why didn't they just call a press conference?

There are much tougher questions for CNN, which in its own reporting buried the fact that it caved to the Justice Department's request for reporter Barbara Starr's email logs for June and July 2017.

CNN lawyer David Vigilante, honoring a gag order the whole time, apparently fought the Justice Department's request from May 2020 all the way through January of this year. He even won a court ruling that CNN shouldn't have to turn over the logs of emails that were internal to the company.

But that, apparently, was what CNN cared about most. So six days into the Biden administration, CNN turned over a list of Starr's external email contacts during the specified time period to the Justice Department.

CNN's official line is that those were "essentially records that the government already had from its side of these communications."

Sorry, that doesn't cut it.

Transparency and accountability for everyone!

Shares