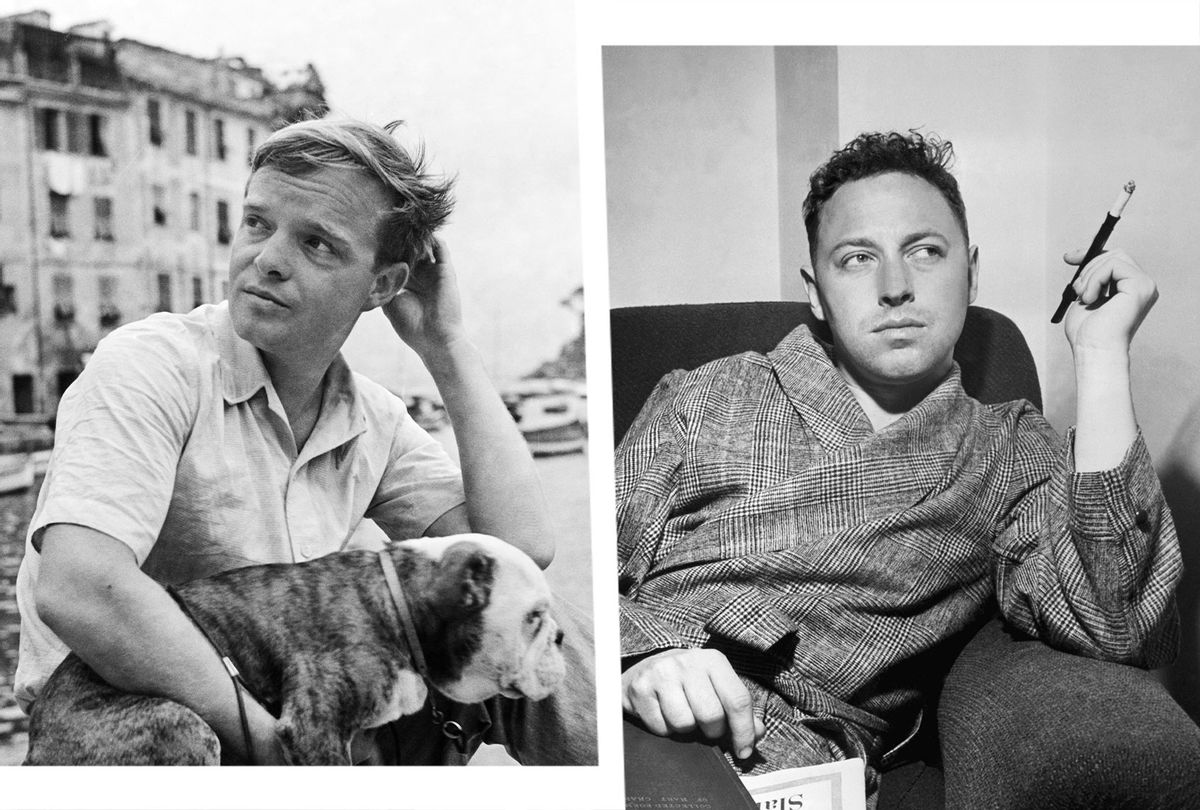

Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams were two of the great authors of their times. The men shared an "intellectual friendship," which is the subject of Lisa Immordino Vreeland's engaging documentary, "Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation."

The film uses images and interview clips with the authors as well as a film clips from productions of their works to trace their careers as they run parallel and overlap. Jim Parsons voices Truman Capote and Zachary Quinto, who appeared in a Broadway production of "The Glass Menagerie," voices Tennessee Williams. The writers' remarks chronicle their thoughts about topics ranging from fame, life in the city, their families, their sexuality, friendships (with others and each other), happiness, and superstition.

"Truman & Tennessee" features anecdotes such as the time Capote and Gore Vidal broke into Williams' apartment and were being interrogated by a female cop, and why Williams thinks viewers should leave the film versions of his plays before the credits. The men are candid — especially when talking about sex on television chat shows — and vulnerable. Williams' observations about his sister Rose are especially poignant.

Parsons and Quinto capture the authors well. In a paired zoom chat, they talked about their own friendship, and what they gleaned from making "Truman & Tennessee.

The film shows how Truman and Tennessee goaded and supported each other over the course of their friendship. What observations do you have about these men and their relationship, which was at times quite bitchy?

Jim Parsons: It was complicated. And what's funny is, I think times have changed a little bit, but I think that gay friendships that aren't romantic friendships can be complicated in a very specific way. I hadn't really thought of that until you asked this question, and I may be completely off-base about this. I have a lot more [gay friendships] now, Zack included, since I did "Boys in the Band" — and I am meeting these people a lot later in life than Truman and Tennessee met each other. I know that I don't feel as competitive with each other in the same the way these men obviously felt with one another. I don't know whether it was the homosexuality, or the fact that they were both writers. Obviously, it was a different era, maybe there was less space for them all to succeed at the same time.

Yes, I kept thinking of Edward Albee, Gore Vidal, and other playwrights and authors at the time.

Zachary Quinto: The phrase "less space" popped to mind before Jim said it. Truman and Tennessee occupied a very specific kind of space in which they were both these incredibly flamboyant people at a time when you really only had two choices: you were either in the closet or so far at the other end of the spectrum, that there was no denying your identity. Both of these guys fall into that category. There was an edge to that at the time; they both were in relationship to, and that edge informed their relationship to one another. They were both incredibly talented in different ways. But they both had this flair that thrived on the give-and-take, the push and the pull, and the exaltation and then the undercutting. That is the beauty of their relationship and their friendship. They motivated each other and probably inspired each other more than either of them would admit.

Parsons: The output of their work, as different as their styles were, they both had a southern lyricism to what they were doing. I don't find them competitive as far as the quality of their output, but it is definitely a specific space they were both emanating from in their own way.

How would you describe your friendship with each other having worked together for a number of years now? Do you push and pull and inspire each other?

Quinto: The foundation is comfort with Jim. It's reliable, it's trustworthy. I'm inspired by him and his talents, but I think we really all feel the joy of sharing experience rather than feeling like someone else's success diminishes the capacity for our own. That's not something we carry with us, that was true of Tennessee and Truman. For me, it's a very comforting friendship when we work together. I wish I saw Jim more.

Parsons: I agree. I've told this story many times in our "Boys in the Band" press. We didn't know each other extremely well before we did "Boys." When we did our first table read of the script, and we weren't sure who was going to do it, I contacted Zack and said it was important to me that you do this. It was a sensation I had that if Zack wasn't playing this specific part when I was playing the other part — there was something anchoring about him in that part that I felt I needed to do the best job in the part I was going to do. That feeling has only grown the more we've worked together and gotten to know each other. There is comfort and inspiration, certainly, but a level of security. The strength of what he does as an artist and performer in general, gives me the room and confidence to do what I need to do on my own.

What interests you about the writing of each of these men? Is there a particular work that speaks to you? Zack, I know you were on Broadway in "The Glass Menagerie" in the Williams role.

Quinto: I was a really big fan of Lisa's before she reached out to ask me to step into this project. I find her a fascinating filmmaker and documentarian. She brings this incredible insight into iconic people and really humanizes them and brings an audience into their sphere of influence with an effortless intellect and emotional thread. When she reached out to me, I thought it was exciting. My connection with Tennessee was really solidified in my experience doing "The Glass Menagerie" and diving into the two incredible biographies of him, and his journals and his writing. There is just no one like him. He is a singular voice who processed his own traumas. I always felt that Tennessee was at once chasing something and running from something, all the time in his writing and his work. And playing his most autobiographical character in his most autobiographical play, I really felt connected to him and his lineage in a way that made me feel this was an organic progression. Not to mention the fact that he was so colorful and over the top and inhabited this persona that's almost unbelievable. It was so unapologetic and unabashedly unique. The opportunity to give voice to that was also really welcome for me.

Parsons: I knew Tennessee very well from seeing and reading and watching movie versions of his plays. I had also read the John Lahr biography, which was just sensational. The only thing I knew about Capote were two films — the film version of "In Cold Blood" and the Philip Seymour Hoffman film. And I guess I knew "Breakfast at Tiffany's," but I didn't connect that to Capote in my head. He was very new to me as far as his writing. I'm just now starting to read "Other Voices, Other Rooms." I was really taken aback even within the first 10 pages. The writing is beautiful. There is a lyricism to it, but it doesn't stop it from being specific and grabbing you with interest. But I was not only a fan of the movies Lisa had made, but also movies like that. Documentaries are my favorite types of movies to watch in general, specifically about any sort of artist, whether musicians or writers or what have you. That was the exciting thing about getting to be a part of this. I was hesitant about trying to do some kind of version of Capote's voice. This was in the middle of the pandemic, so before I got vaccinated, this was my favorite thing I've done all pandemic long. It was an odd, beautiful creative outlet.

Both writers discuss fame. They don't care what is said or thought about them. There is also a comment in the film about having a "fantasy of affirmation" — that success is a way of getting back at the schoolyard bullies. What can you say about the power of celebrity?

Quinto: The nature of fame has changed quite a bit since their day, and not necessarily for the better. Fame is a complex construct to begin with. Now it means less in a way, right? To be famous at a certain time, like they were, required a refined skill set and a declaration of creative prowess that was substantiated by a community, and reflected in a kind of elevated work that we don't see all the time anymore. We still see it occasionally, and there are still those of us who aspire to that. But fame has become a different thing. For me, the balance is always about being able to really live my life fully and in as integrated a way possible. I don't like to have my personal experience defined by any kind of notoriety or celebrity status, and that's a commitment that I made to myself early on, before I really understood what fame was. Now I just live my life and whatever people feel or think about me is none of my business. That has been a helpful reminder along the way. Jim came into people's homes for 12 years. My [fame] comes in waves — the Trek world and the sci-fi world — but we share a fanbase. There is a different kind of accessibility that people project onto that, so he has a different experience of it than I do.

Parsons: I think both of us, and a lot of people I know, for whom the fame aspect is important to them. It was certainly important to Truman, it seems, but I don't doubt that Tennessee enjoyed it a lot, too. I think one of the reasons is, as Zack points out, it was a different moniker then. It was a different badge to carry. It meant something different than it does now. Both of us and people we're close with, I don't think that — without saying you're running from it or trying not to have it — it's not necessarily something you are excited to have as a part of your life every day. It's something that's there, and for a good reason, and you're fortunate it's going on. But I'm not interested in throwing a Black and White Ball. It's really not my thing. To give Truman credit, he knew how to utilize that; it gave him fuel for his fire and his output. Other than helping me keep working by just people knowing who I am, I don't' find [fame] overly helpful in the creative process. I think, if anything, it would only be a distraction for the most part. Which is not to complain about it or say I don't see the good things behind it, but it's just different.

Yes, it has changed over time and the television talk shows where Truman and Tennessee were seen in living rooms and they are asked about their sex life! You couldn't do that now!

Parsons: To that point, the clips of them in their interviews in this film itself, I can't believe the number of interviews both of these men did that allowed them to do the expansive talking and discussion of topics. We don't have as many [outlets] that do that anymore, and, if anything, we've geared more and more to making a point or splash immediately. They are just so expansive in these interviews!

Are either of you superstitious like Truman and Tennessee were?

Quinto; I don't know if I'm superstitious. Sometimes I employ magical thinking, like if I cross the street before the red light. But not really.

Parsons: I feel exactly the same. I've done some magical thinking, which I think is OCD to be honest, but whatever. I'm not running to go under a ladder or put a hat on a bed. Why tempt fate? I'm not saying the Scottish play in a theater. I don't find it crippling and I wouldn't force someone to trade hotel rooms, though.

What about happiness, which is something discussed in the film, and described by one writer "as being like an orgasm or a sneeze?" Both writers talk about loneliness; they struggled with depression and alcoholism and self-destruction, arguably at the hands of Dr. Feelgood. What are your observations on that? I thought that was really revealing about both writers.

Parson: I agree. With the obvious part out of the way, that it's a very different thing to be gay now than it was then, I feel afforded an opportunity for a happiness that I don't think was as easy to obtain at that time. Deeper than that though, both of their reactions to those questions gave me pause, because it seems to me that it wasn't just about homosexuality or even being a tortured artist but an element of just being a human being. And listening to them talk about it, and they are both so intelligent and thoughtful, I did find myself questioning how happy am I truly? I think that I am happy most of the time. I claim to be happy a lot of the time. I strive to find happiness and satisfaction in my life — especially in regard to things away from my career, because I don't want that to be hinged upon that kind of success or work. But the mere fact that I think about this as often as I do, and that I'm striving to maintain a health and happiness says to me that it it's a tricky business. It may be, to varying degrees, a universal, lifelong struggle of getting through — getting through, see, even that word choice! — to journey through your life in as present and happy a place as you can be. I don't know what it is that is the gravitational pull pulling you down from constant elation, but it is real. There is always something to pull at you, and the joyful struggle is to keep going.

Quinto: I also think that the integration of trauma and people in our lives who fell short, or disappointed us, or abandoned us for various reasons along the way is a huge key to that. I know in my own journey and experience, that has been an incredibly important part of my fulfilment — looking at those aspects of myself and not shying away from them. We also have the advantage in this day and age of living in a culture and a society in which that is not only acceptable but encouraged. That wasn't true of the generation from which Truman and Tennessee emerged. We have more agreed upon vocabulary and social contracts for diving into our own psychodynamic experiences. I know personally that I benefited from that. I don't know if I would have been able to overcome some of those gravitational forces if I didn't have that. They didn't have that in their families and in their society. What they had was a bottle, or pills, or things that were distractions, or tools of escape. I understand what that instinct is myself, and I am grateful to have been able to recognize that it is not the direction in which I want to move. They didn't have that luxury, and it got its hooks in them and wouldn't let them go.

Parsons: I feel exactly the same way. When I see on the screen in the end of the film that Capote died at 59, and a lot of the footage leading up to that — you can see the wear and tear of that life. It's like the old footage of Judy Garland. You just can't believe she wasn't even 50 yet when she died. It's not just that we have better medicines and better food around us. It is, to Zack's point, that hopefully we are learning from the footfalls in front of us of other people in trying not to do it. There is nothing that those two men are experiencing or giving themselves over to those demons that I don't at some level identify with.

Do feel there are any contemporary writers/playwrights that arrest you in the way Truman and/or Tennessee do?

Quinto: Hmm. Interesting question.

Parsons: First off, it's a hard question to answer because Truman and Tennessee were icons by the time I was born. I wrestle with this just as a working artist of wanting to work with "Who's the next . . ." you fall into it accidentally most of the time, and only 20 years later go, "Wow, what a genius . . ."

Quinto: Working with Tony Kushner. To be in the presence of someone who is that exalted in his own time and rightfully so, really transforms the theater. And to get to do the first New York revival of that play was an incredibly profound experience. I had a level of reverence for him and his work that approximated how I feel about Tennessee and Truman. But it is hard, like Jim says, to really know which reverberation will still be echoing in generations to come. To know those people and to have relationship with them, you step back from those moments and look at them from the outside and think, "I'm interacting with someone whose work will be around long after we're all gone." It's humbling and beautiful. It is a real character of the city and the community of New York.

Parsons: I re-watched "Truman & Tennessee" a couple of days ago and it hit me all over again coming out of the pandemic — that section about life in New York as a character. It just seems an eternal thing. Truman speaks my language when he says that about pavement.

What did you come to appreciate about these writers from making the film?

Quinto: I appreciated what they were to each other, which is something that I didn't know before I worked on this film. Catching a glimpse of their personalities through their letters and through the way they treated one another and through the way they talked to one another and about one another. There's a kind of prickly playfulness that exists between them that captures something ephemeral and carries it through the intervening decades since they've been gone. I love that about it. I'm such a firm believer that we are all connected through this lineage of creativity, and when a person leaves the earth, that energy doesn't go with them. It exists for others to step into and experience. I felt that connection to Tennessee often doing "The Glass Menagerie." To have the opportunity to being exposed to dynamic and relationship was reaffirming of that belief.

Parsons: I was really moved by each of their devotions to their craft in that way. By the end of the movie, both of them have parts where they are kind of saying, "This has been really hard." Truman is very pointed about it, but Tennessee is in his own way, too; how painful it was for him to not have the critical success with his later work. But they both just kept working. It was lifeblood to them. They put so much of their spirit and their heart into the work. That's why it stays around long after they are gone. That is where other people can take it, and interpret it, and let it live through them, and therefore, they live on. Not everyone's capable of it, and perhaps more than that, not everyone is willing to. I think there is not even just a discipline but a sacrificial quality about both of their ways of working. There is blood in it — in the best way.

"Truman and Tennessee" is now available in select theaters and through virtual cinemas at KinoMarquee.com

Shares