Unearthed, an environmental news team run by Greenpeace UK, recently carried out an undercover investigation into the oil giant ExxonMobil, in which the team posed as corporate headhunters and recorded two of the oil giant's top U.S. lobbyists soberly admitting that the company has systematically suppressed climate science and pushed lawmakers to impede meaningful climate action.

The two lobbyists — Keith McCoy, a senior director for federal relations at Exxon, and Dan Easley, a former Exxon White House lobbyist — helpfully outlined a number of ways in which Exxon has successfully squashed federal environmental regulation in service of its bottom line over the past decade.

McCoy boasted that he had personal relationships with a number of Democratic senators friendly to the oil industry, including Jon Tester, of Montana, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and the famous or infamous Joe Manchin of West Virginia, whom McCoy described as a "kingmaker," saying he calls Manchin every week to discuss Exxon's political interests.

McCoy characterized Exxon's public support of a carbon tax, which would put a price on emissions, as purely a PR ploy designed to convey the impression that the company is environmentally conscious. The company's stance, he said, is merely a "talking point," because "a carbon tax isn't going to happen."

McCoy even said that Exxon often sends oil industry trade groups like the American Petroleum Institute to lobby for the company's interests as its "whipping boys."

Perhaps most noteworthy in Unearthed's report was the claim that Exxon played a direct role in shaping President Biden's infrastructure bill. According to McCoy, the company has been working to nix a carbon tax that was originally included in the bill to fund the construction of clean energy infrastructure.

"Did we join some of these 'shadow groups' to work against some of the early efforts [at regulation]? Yes, that's true," McCoy said. "But there's nothing illegal about that. You know, we were looking out for our shareholders."

Unearthed's findings have made headlines in just about every major U.S. news outlet, providing smoking-gun evidence of a back-scratching relationship between Big Oil and political insiders that environmental advocates have long argued exists behind closed doors.

To get a better sense of the report's significance, Salon spoke with Lawrence Carter, a senior reporter and special projects editor at Unearthed. Carter himself conducted the sham interviews and helped lead the investigation alongside editor Damian Kahya.

The idea, Carter said, was born out of previous investigations into BP, the British multinational oil and gas company now infamous for spilling more than 200 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Carter explained he had been "carrying out investigations into oil companies that have claimed to support the Paris Agreement but [didn't] actually seem to back it up with their actions," whether that meant the company's actual emissions or its lobbying positions.

BP was one of these companies, Carter said, purporting to be a leader in tackling methane emissions and "flaring," a high-emissions practice in which nonviable gas is burned off for safety reasons. Behind the scenes, Carter discovered, the energy mammoth has done just about everything it could to flout its public Paris-aligned position.

In 2009, for instance, a year before the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP lobbied the Obama administration for an exemption from a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) rule that would have required the firm to produce a report on the potential environmental impact of the Macondo Prospect, the Gulf of Mexico oil field where the spill would soon happen. More recently, as Unearthed reported, BP lobbied in 2017 for a legislative dilution of NEPA, weakening the requirement for oil and gas companies to predict the "cumulative impacts" of potential projects in order to receive federal approval.

Though Unearthed's findings went far beyond what was publicly known at the time, Carter acknowledged that the team's investigations were limited. In the case of Exxon, he said, "we ultimately came to a conclusion that an undercover investigation is justified and necessary to reveal what they're really doing."

The decision to pursue such an investigation was the result of a "painstaking" process, Carter said. "We had to find a very large body of prima facie evidence to justify doing the investigation at all."

A key piece of that evidence came from revelations about where Exxon was directing its money with respect to political advocacy. In 2016, a bombshell report by the Guardian found that the oil giant had known about the correlation between climate change and carbon dioxide emission as far back as 1981. Despite this, the company funded a number of right-wing interest groups that have systematically denied the connection, according to Greenpeace. These groups have included the Competitive Enterprise Institute, the Heartland Institute, the International Policy Network, the George C. Marshall Institute, the American Legislative Exchange Council and a number of others.

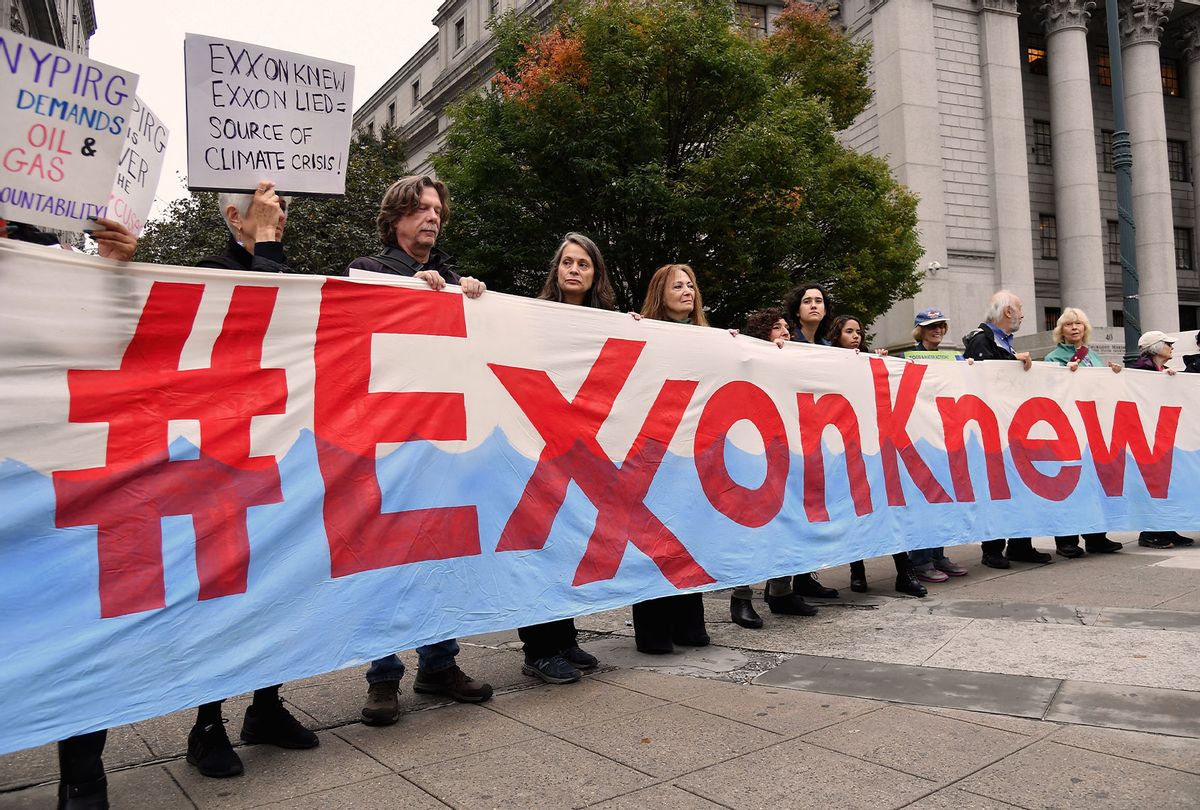

Shortly after the Guardian report surfaced, a broad public awareness campaign — dubbed @ExxonKnew on social media — coalesced around the oil company's apparent complicity in climate change and climate denial. "Exxon knew about climate change half a century ago," the campaign's website read. "They deceived the public, misled their shareholders, and robbed humanity of a generation's worth of time to reverse climate change."

Going into the Unearthed investigation, Carter said "there was some trepidation about what a $300 billion oil company is going to do in response." This investigation arrives amid an acrimonious legal tangle between Chevron and environmental lawyer Steven Donziger, who successfully sued the company on behalf of 30,000 Ecuadorian farmers and indigenous people affected by Chevron's operations in that country. Chevron retaliated with a legal onslaught alleging that Donziger effectively ghostwrote the report that led to his success in court. A federal judge ruled in Chevron's favor, and Donziger has been on house arrest since August 2019 after refusing to surrender his laptop and cellphone, claiming that was a violation of attorney-client privilege.

Not eager to face a similar fate, Carter said he had consulted a number of lawyers before launching the investigation to ensure it would be conducted legally.

Neither McCoy nor Easley responded to Salon's request for comment. A spokeswoman from the American Petroleum Institute (API), which McCoy described as Exxon's "whipping boy," responded to Salon with this statement:

API is out front and transparent about whom makes up our Board and where our industry stands on policy issues — and we proudly disclose and advocate for both, either as API alone or as part of broader coalitions of manufacturers. Our industry has a long public record of supporting policies that enable the safe and responsible development and use of American energy and other petroleum products while reducing emissions and protecting public health.

The spokeswoman declined to address McCoy's comments specifically.

Exxon, which also did not respond to Salon's request for comment, has released a public statement attempting to distance the company from McCoy and Easley.

"We condemn the statements and are deeply apologetic for them, including comments regarding interactions with elected officials," said CEO Darren Woods. "They are entirely inconsistent with the way we expect our people to conduct themselves. We were shocked by these interviews and stand by our commitments to working on finding solutions to climate change."

Carter told Salon that Woods' statement "stretches credulity."

"It's a bit of a coincidence, isn't it?" he said. "That we just so happened to speak to the only two bad employees in their lobbying team — and that they were running some kind of covert lobbying operation behind the company's back. It's not the sort of behavior you'd expect from a major company, to blame their staff."

Carter said he had "spoken with a couple of reporters" about the striking statement from Exxon. "They all said they can't remember the last time Exxon apologized for anything."

Shares