It's the year of the female antihero. From "Promising Young Woman" to "Kevin Can F**k Himself" to "Physical," the pissed off woman is everywhere, wreaking havoc, getting revenge and maybe blowing up her own life in the process. Now, Joan has entered the chat.

"Animal," Lisa Taddeo's follow-up to her sensational nonfiction bestseller "Three Women" is the tale of a self-described "depraved" New Yorker, forging a tragedy and violence-strewn path toward a younger woman whose life seems a GOOP fever dream of perfection. One recent review has described the novel as an "American Psycho" for the #metoo era — a comparison that's simplistic but also should really make you want to read it.

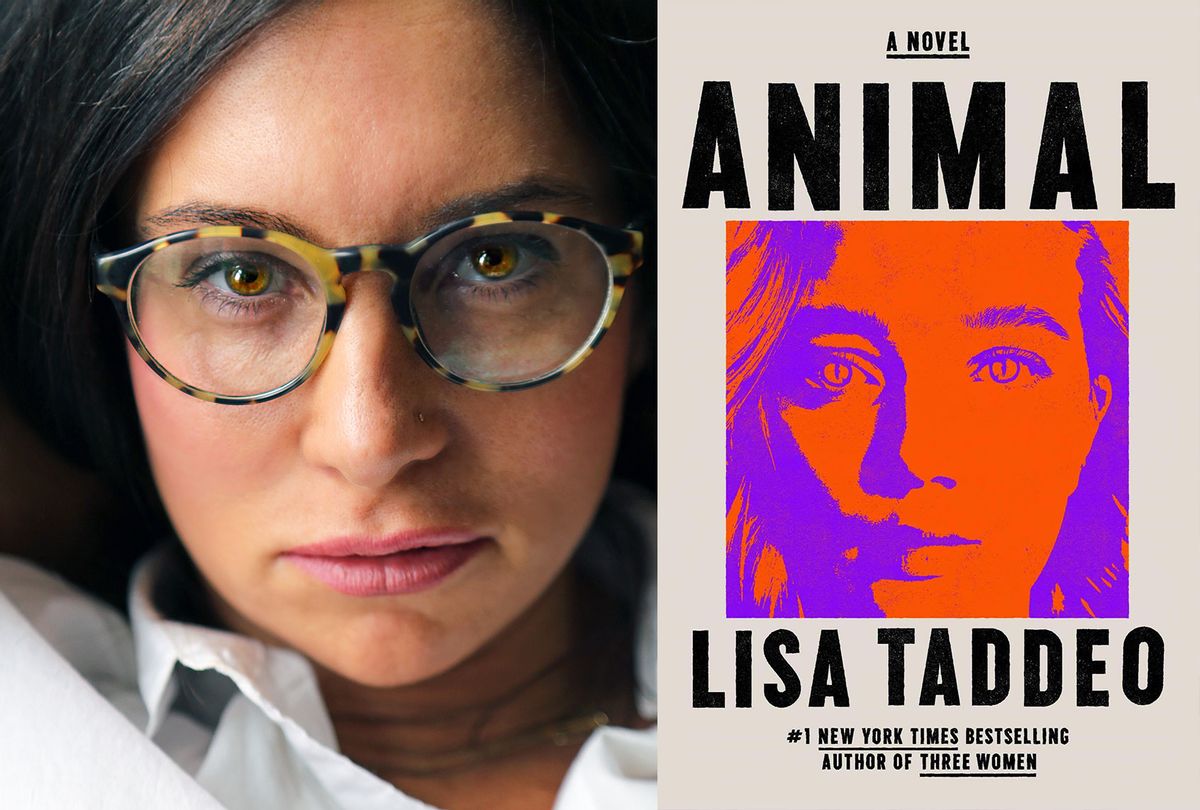

Taddeo appeared on "Salon Talks" recently about what inspired her to write one of 2021's most talked about books, about female anger and about what makes a "summer read."

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

This is a book that women are going to be quoting for years. One that really stands out is, "We are all monsters. We're all capable of monstrosity." That is also a foundational bedrock of this story. Tell me about Joan, the monster she is, the monster she has become.

Joan is a woman who we meet in a restaurant in New York City. She is having dinner with a man who is married, and another married man comes in and shoots himself in the face in front of her. What follows is basically why and how she got to that spot where a man would do that. What are the things that she did to, quote-unquote, "deserve" that, and moreso why do we think somebody "deserves" something? Why we do root for the people we root for, and don't root for the ones that we don't? I do believe as humans, and it's something I wanted to look at in "Animal," that we are all capable of doing terrible things. The reasons we do those things are most often not because we're born with some bad seed, but because something has driven us to this sort of point of no return.

Things have been happening collectively to so many oppressed people. I focused on women, but for me it's really the whole idea. "Animal" is for anyone who has been oppressed and knocked down, and then upon trying to rise back up, was looked upon as a monster for doing so. I'm really happy you brought up that quote in particular, because it really does mean so much for me. It is so much of why I wrote the book.

Joan is telling her story to a reader. She's using direct address as she calls herself "depraved." At first you're wondering why she's doing it, and then you can see how it's defensive. She is very, very sophisticated in the way that she reveals herself.

That's exactly it. It's defensive. We see so often in society when certain people have been beleaguered for a long period of time, they get really good at calling out what their opponents are going to say to them or call them, thereby owning the insult themselves. This is something that Joan is very proficient in. After years of being called names by men and her fellow women, she has come to this point where she's like, "I'm going to say it before you do." When she calls herself depraved and mad and all of the things she calls herself, she's saying, "Look, I fit this definition because of X, Y and Z." But she's also mocking the very nature of name-calling by saying, "This is what happened to me. Do you still want to call me those things? Or do you want to talk about where it actually began?"

We hear all of Joan's story from when she was a child and from all the biggest experiences that render her the monster that she claims to be and become. What we're really not getting is the full story of all the people who did that stuff to her, and where their history of trauma comes from and why they're doing the things that they do. That's really the point, that we're just looking at Joan. That is so interesting to me. I did a lot of research for "Three Women" on pedophilia. Most of them have had things happen to them sexually when they were children themselves. I think it gets to this cyclical nature of just trying to deal with the symptoms and not the actual heart of the disease. Joan, in a sense, beyond being our sometimes unreliable narrator, is also someone who very much understands all of that, because of the way she's been treated and the things that have happened to her.

Whether we're looking at it from a macro level of post-pandemic, or one person's grief, it's there in that phrase "back to normal." That you go "back to normal" as if you can return in time to that person you were before this incredibly traumatic, upsetting, devastating, life-changing thing happened to you.

It's like, how is your life interrupting someone else's? It's always this idea, that everybody just wants to be part of the same mouse wheel, and if anyone gets kicked off, we're just like, "Oh God." We thrive on that routine, and that sense of order, because we're all very afraid. I'm the most afraid person in the world, I feel sometimes. It's that danger of looking at others and feeling like others' paths are somehow dictating our own, to an extent that we feel like we need to dictate theirs.

You wrote this book in that space between finishing "Three Women" and "Three Women" being published. I know there were stories in "Three Women" that you didn't use or couldn't use, and you also obviously draw on your own life. I'm wondering how that first book informs this one.

It informs it. A lot of the things that I was writing about in "Three Women" and talking to women about, I was like, "Oh, that's going to be too dark for this," and not because I was trying to have people read it and be happy. It wasn't that. I just was under this correct notion that people wouldn't listen to the stories at all if there was one thing that smacked of something that was not sympathetic enough. My biggest goal was to make all of the women feel, just to make everyone feel, not empathy for them, but see themselves in them. I knew that it could both be additive and reductive to the goal to tell the parts that I knew were a little bit too dark because on the one hand, there'd be people who would identify even more with the woman, and then there'd be another half of the people who would take whatever they had felt up until then and would be gone.

In "Animal," I was like, "I'm not going to be worried about this," because it's a fiction. It's a novel. There's a lot of truth in here, but it's also not like "Three Women." I really made a conscious decision to say whatever all the truths were that I had heard, that I myself had experienced. I knew that there was going to be that "American Psycho" feeling about things. I knew it because I'd seen it with "Three Women," so I was prepared and I'm not surprised. It was important to me nonetheless, to continue doing it.

I think that part of what we do to each other is we really do try to censor one another's stories. We do it so much. It's like we have all these trigger warnings. I have my own trigger warnings, things that will wreck my entire day if I see or read about. We have this way of making our own trigger warnings be someone else's responsibility to the point of the person for whom talking about their trigger warning is a catharsis, becomes unable to do it because they might upset somebody else. There's a lot of selfishness involved in telling stories, and in not telling stories, and deciding who can tell them and who can't. Quote-unquote "bad women" are not allowed to tell their stories still. We — I'm saying "we" because I've been bad in the way that sometimes my mothering is bad. I'm often a bad wife. I'm saying it in that same way that Joan does, not really believing that bad is bad, but that it's human, and that I'm being honest about it. I prefer to be super honest about emotions than talk about stuff that is not interesting to me.

Then there's this one character who seems to have it all together. I read something you wrote about how people will always believe that a woman could be that perfect. People don't question that she's perfect and sexually available and she's beautiful. And that is so much more credible in a fictional story than the woman who is just falling apart, and is the madwoman in the attic.

We just don't want that woman to exist because I think she's in all of us. We've been told that if we show that, that we are going to be ejected from society. We have to be cool. There are things that it's okay to talk about now. It's okay now to talk about mental health. It's getting okay to talk about miscarriages. I'm saying that very expansively. I don't know exactly what is okay and what is not okay. What I do know though is because I've just published a book about a woman who is falling apart, I know that it's not okay to do that because I've been told that it's not okay. A woman has to be a victim in the right kind of way, and she has to fight back in the right kind of way, and the fact that we don't see that, that we don't allow for women to be more complex characters, is part of the sort of hysterical blindness that we have.

It really pissed me off about "Three Women," with Lina in specific — the woman in Indiana who has this affair with her high school lover because her husband didn't want to kiss her on the mouth anymore — people were like, "Oh, she's pathetic. Why are you talking about this pathetic woman? Why did you decide to tell her story?" I find that so mind-boggling. Who's arbiting that? Who's the judge of whose stories are good? You can say you don't like a story. That's fine. But, "Why are you telling that story?" is a really dangerous question to ask.

Someone asked me this morning, "Is this a summer read?" I said, "I mean, maybe. It depends on what kind of beach reader you are." If I were to tell a friend, "This is your beach read. Take this one on vacation," what would you say?

I would examine who the person is, which beach reader we're looking at. For me, it is a beach read. It was a beach write. It's a beach read. This is the level at which I operate. I don't like reading books that I will forget about within a couple of weeks. I don't like consuming any art that is forgettable. I don't want to create any that is either. And that's not to say that beach reads are forgettable at all. For me, I guess this is the closest I could come to writing a beach read. So hopefully it is, for some people, a beach read.

Shares