How much did you perspire today? How much did you think about it, attend to it? Did you, as I did, swipe on some antiperspirant before your workout and then sweat through your gym clothes? Did you notice droplets forming on your neck throughout the day, as you walked outside, cooked a meal, kissed a lover, flubbed a work presentation? Did you fret that your sweat was telling on you?

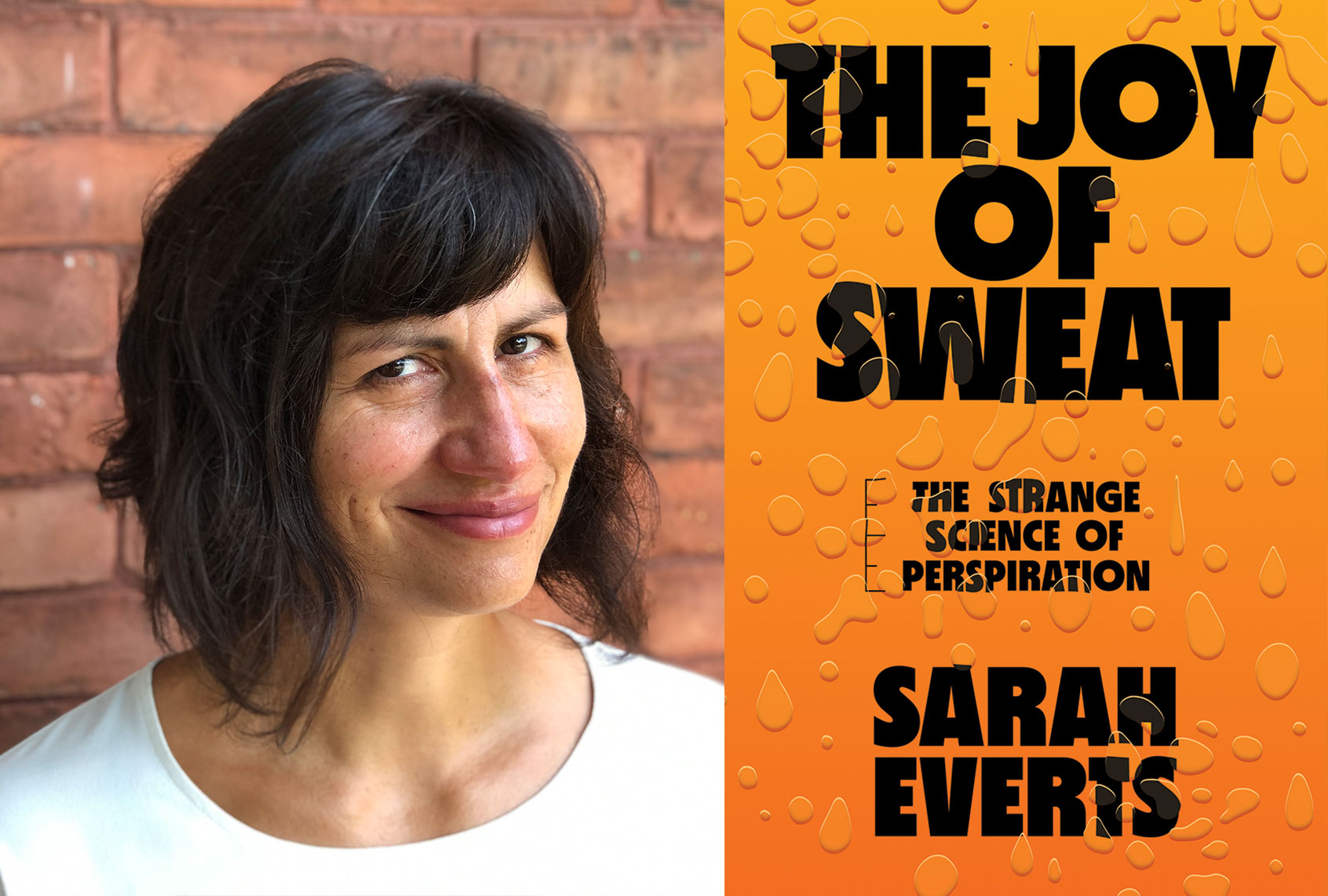

Sarah Everts was curious too. Despite our obsessive and often counterproductive cultural “war on sweat,” the science journalist knew that our perspiration is a big part of what makes us human. Our sweat regulates our bodies, and it helps understand each other, even if we’re not aware of any of its power. Salon spoke recently via phone to Everts about her entertaining new book, “The Joy of Sweat,” about our surprise superpower, why our odor aligns with our bestie’s and the “bacterial poop” that makes us stink.

Why write a whole book about sweat?

Like a lot of people, I have always slightly mortified by my sweat, and slightly worried that I sweat too much. During workouts, I am the first to grab a towel, even during the warmup.

As a science journalist and a recovering chemist, I decided, I have the tools dig into this, to learn more about this thing that’s causing me some anxiety and maybe find some serenity, instead of shame from all of this.

Around the same time that I was thinking about sweat, I also moved to Berlin, Germany, and everybody there goes to the sauna for fun. I was like, “Why would you sweat for fun?”

I realized there’s this amazing catharsis that you have going to the sauna. It’s a place where everyone is sweating profusely. You’re supposed to sweat profusely. It’s just this delightful thing that turned me on to the joyous part of sweating.

There isn’t actually a whole lot of literature about this thing that, as you say, we are doing constantly.

Not only are we doing it constantly, but it’s humans’ evolutionary superpower. Along with big brains and near nakedness, sweating is one of the ways that we are amazing in the animal kingdom. We’re super efficient at temperature control. It means we can run marathons. Over our evolutionary history, it allowed us to hunt prey that ran much faster than us.

Most of our prey sprint faster than we do, but humans can trudge along, run after it, and once we catch up, force them to sprint again, because they have to stop to cool down. Meanwhile, we can cool down while on the run, and, in effect, outrun our prey, forcing them to die of heatstroke. Heatstroke’s a terrible way to die, and we have this embedded biological system, millions of little tiny machines in our skin, pumping out sweat to keep us cool.

Yet we are also super wasteful sweaters.

Some other animals do sweat to cool down, like cows and horses, but humans are so much more sweaty. We produce so much more fluid than other animals. We’re also that much more efficient with it. It’s partly because of our nakedness.

Our closest primate cousins, chimpanzees, have body-wide sweat glands like humans do, but they don’t use it really to cool down. They pant like dogs. You need to evaporate water away from your skin to get that cooling effect. Their tongues are the nakedest part of their bodies, whereas we have our whole surface area, our whole bodies, as a surface to cool down.

The ideas of sweat and smell are obviously so deeply intertwined. What can our sweat tell us about ourselves?

We learn so much information about one another through body odor. It starts at birth. Just hours after a baby is born, parents can identify their newborn based on its body odor. Siblings can identify each other even after spending two years away. We all have our unique smell print, but there are other interesting bits of information that emerge in our body odor.

We can sniff out anxiety among each other. This is really interesting research that stemmed from an observation from law enforcement. People who do interrogations observed that when you bring in somebody for questioning, they smell like themselves, but after an hour of stressful questioning, they all leave smelling the same of this potent stink of anxiety.

Researchers who followed up on got people to watch a video, one a nature documentary and then another one a scary film. They collected their body odor on t-shirts, then gave those samples to a panel of sniffers who distinguished who was stressed out and scared versus who was just a normal human.

There’s also just interesting ways in which researchers have found out that we can probably also smell our immune systems at work. You can imagine that for most of human history, this has helped us figure out if somebody is infected and maybe avoid that person. We maybe do it unconsciously, just by thinking, “That person doesn’t smell as appealing to me, I think I should take a step away.”

To that end, I was surprised reading about how people shake hands — and then will smell their hands. It’s such a beautifully primal, animal thing that we do.

Scientists based out of the Weizmann Institute in Israel took videos of people meeting for the first time. What they found was that they’d have two people meet and shake hands, and then afterwards they caught people on camera sniffing their hands. It was so unconscious that many of the subject participants. when shown the videos afterwards. accused the researchers of having done some clever editing or somehow faking the videos.

The idea is that when you meet a new person and you shake their hand, you get a body odor sample of them on your hand. We are sniffing out these new individuals. That same researcher just found that people who become fast friends, when their body odors are assessed by a body odor panel, have more similar body odor profiles than any two random people sampled. If you think about most human greetings, it brings us in close proximity to one another. Whether it’s a bow or a cheek kiss, we get this opportunity to take a sniff.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

I was also intrigued about how just sharing a bed with someone can change our microbes. Can you talk a little bit about that can change the way you smell?

This is really fascinating work from a guy named Chris Callewaert who’s got the best Twitter handle ever, Dr. Armpit. He had a tryst with a woman, and he said through most of his life prior to the tryst, he had not really had much of a strong body odor. Afterwards he noticed that his armpit odor changed dramatically. He found it to be a lot stronger and a lot more stinky, and he was perplexed by this. But he also was interested in doing a PhD, and he decided to investigate this as part of his doctorate. He started analyzing the microbial makeup of his armpit because, as we know, the reason our armpits stink is thanks to a sweat gland that becomes active at puberty.

This is not the sweat gland that produces all the salty stuff that helps us cool down. This is one that becomes active anywhere where you grow hair at puberty. We have bacteria all over and in our body, but the ones that we get in our armpits, we metabolize it and turn it into the stink that emerges out of our armpits. It’s actually not your sweat that stinks in your armpits — it’s the bacterial poop.

Callewaert began to study the populations of bacteria living in our armpits and became interested in the possibilities of doing a transplant of the populations of bacteria living on our skin. Ultimately, he managed to re-transplant his original microbial population, in kind of a freak accident. He had this old t-shirt that he has used years before that was covered in paint and that he hadn’t actually washed. He put it back on and painted for a day. His old armpit microbiome was on the armpits of that shirt, and he kind of repopulated himself with his old bacteria. He went back to smelling like himself.

It does make you question then what happens when we spend a lot of time sleeping in the same bed with someone and the implications then for our own microbial portrait.

Callewaert actually found that it’s really hard to transplant other people’s armpit microbiomes. It’s very rare that this is actually successful, so he had a really strange occurrence with that tryst.

The most success he’s has is with identical twins who clearly have some of the same genetics. They probably have grown up in the same environment, have probably recruited the same bacteria into their armpits as each other, and therefore, can hold a new ecosystem that maybe produces less stink.

I want to ask you about the stink aspect, and “the war on sweat.”

We have been worried about our body odor for thousands of years. Here’s some advice from the Roman poet, Catullus, who says to his nemesis:

You are being hurt by an ugly rumor which asserts

that beneath your armpits dwells a ferocious goat.

This they fear, and no wonder; for it’s a right rank

beast that no pretty girl will go to bed with.

So either get rid of this painful affront to the nostrils

or cease to wonder why the ladies flee.

For most of our history we have worried about our body odor, but we’ve mostly dealt with it with perfumes or by washing with soap and water, and then adding perfume to overwhelm or compliment our body odor. But around the turn of the 20th century is when deodorants and antiperspirants get invented. They were invented, in part, by doctors who have discovered antiseptics. Because body odor is mostly caused by bacteria, deodorants are just antiseptics you put in your armpit and kill the bacteria that gives you stink.

Whereas, antiperspirants end up being a product that clogs your pores and so, they cut off the sweaty buffet the bacteria that would eat it and then turn into stink. That’s the strategy for stopping stink and wetness that develops around the turn of the 20th century. And nobody wants to buy them. Everyone thinks that water is frankly good enough and nobody want to talk about stink or sweat. Certainly drugstores are not going to put these products on their shelves.

All these early entrepreneurs just don’t know what to do, they can’t get a hold on the market. This high school girl named Edna Murphey figures out a way around it. Her dad had actually invented an antiperspirant for his hands, because he was a surgeon and was worried about dropping surgical tools into his patients during surgery in the hot summer months in Cincinnati. She starts a small company and starts promoting this product called, “Odorono.”

But like everybody else who’s an early anti-sweat entrepreneur, she’s getting no buy in, until she hires a marketing team from J. Walter Thompson. In particular, they give her this copywriter, who with one advertisement in Ladies Home Journal puts the fear of stink in America. The advertisement starts off about how “the curve of a woman’s arm” should be this beautiful place. But it’s actually not, it’s a stinky horrible hellhole. He effectively alludes to the fact that women’s armpits are a stink zone. He says to women that not only are people talking about you behind your back, but this is going to interfere with you getting a husband. It is 1919. People were so offended by this ad that they canceled subscriptions to Ladies Home Journal, but so many people were struck by the ad that sales of Odorono skyrocketed. Soon everybody in the anti-sweat industry was using this strategy, which even has its own name, “whisper copy.”

By the time the thirties roll around they’ve managed to get buy-in from most of the women in America and they want to expand their market. They’re like, “How do we make more money? Oh, men smell, too.” Instead of working on fears of not finding a romantic partner, they prey on another social fear, stinking in the workplace, or in particular losing your job. Because it’s the Depression era, a lot of the ads that first target men focus on the idea that you’re going to stink in the boardroom and it’s going to cost you a job or a promotion or your career. You can still see that today. It’s no longer just women and romance and men and the career, but now you see similar strategies aimed at everybody in the population. It’s all preying on our fears of being socially excluded or socially isolated.

Often in popular culture, whether it is fiction or news media, the sight of someone perspiring is just an instant shorthand for desperate, scared, losing. Did you, when you were writing this book, did you become more sweat aware?

Sweat is often used with this derogatory framing. That if you’re sweating, you’ve got something to hide. Or, it speaks poorly about your fitness level — both of which are entirely wrong. Excellent athletes actually sweat more than the average person, because their bodies have been trained to know that they’re going to have to cool down, because when they get going it’s probably going to be some hard exercise for a long time. I do find that mainstream media, sweat is not presented as this amazing evolutionary superpower, but as this mortifying thing that reveals your secrets.

Humans love to be in control, particularly of our image. Of all our bodily fluids or bodily functions that cause us embarrassment — I’m thinking farts, burps, pee, poop, all of those other things — we can hold back for at least a microsecond, so that you can step away from your party or the person you’re talking to and do whatever you need to do. With sweat, there is nothing we can do to stop the floods when they get going. When our body gets that temperature directive, we just start sweating.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.