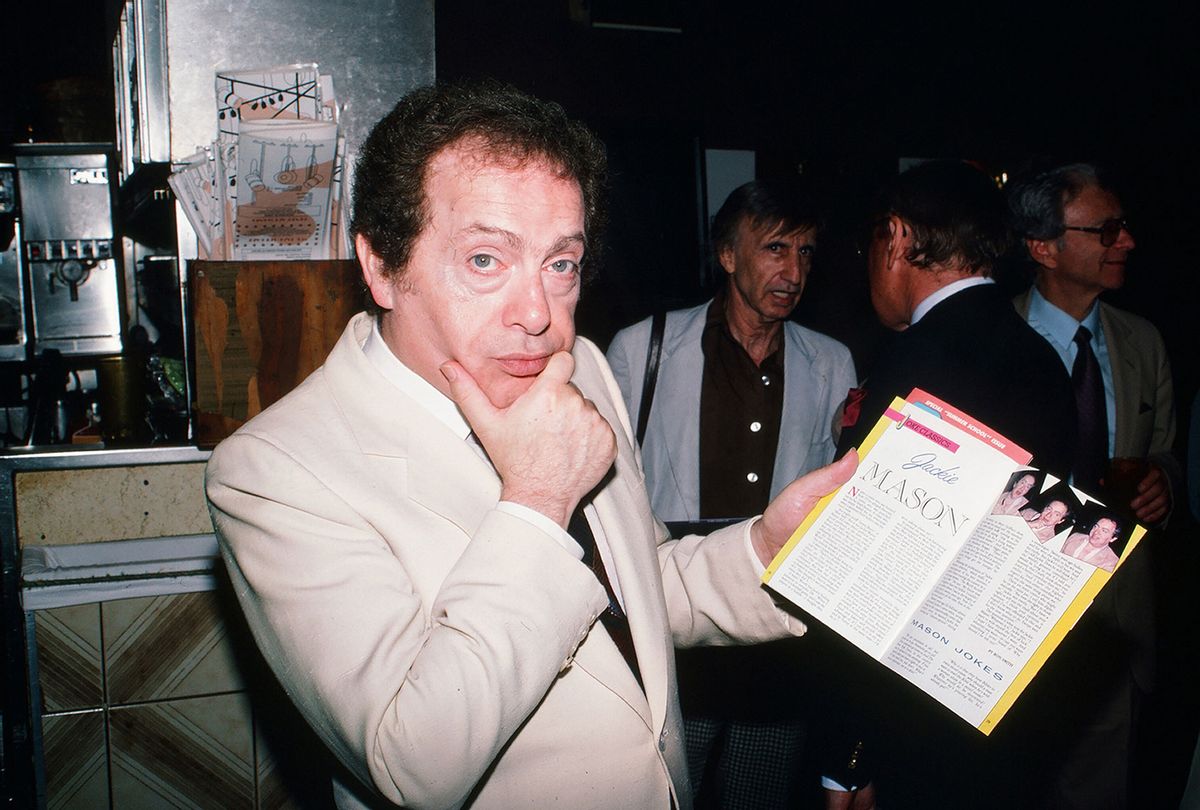

Jackie Mason died on Saturday, and if you only learned who he was during the last five years or so, you might have thought "Good riddance." By the end of his life, Mason — an accomplished Jewish comedian with a legendarily up-and-down career — had become a Trump supporter known for cantankerous appearances on conservative talk shows. His early years, however, were marked by a triumph over antisemitism. Still, by the time he passed away at 93, whatever remained of his great comic gifts — timing, wordplay, and brio — had become tools of the worst sort of Zionist propaganda.

When he was young, comedy was a secret life that Mason — whose given name was Yacov Maza — had to hide from his family. The Mazas were members of an Orthodox rabbinic dynasty from Eastern Europe, renowned for their learned wisdom. His older brothers became respected scholars, just like their father Eli, but young Yacov's dream was to make people laugh. For a while, though, he tried to live up to his family's expectations.

While studying at Yeshiva to become a rabbi, Yacov spent summers working in the Borscht Belt. To avoid his father's wrath, he had to pretend the experience was only a well-paying hobby. He started as a schlepper (a handyman and waiter), moved up to tummler (a jokester whose job it was to keep guests happy), and finally emerged as a full-fledged comedian. His speech rhythms and thick accent couldn't have been any more Jewish, but in the Catskills, where many resort patrons spoke Yiddish, he fit right in.

One year, between gigs, Yacov attended the live broadcast of a radio show that invited audience members to perform on the air. He was lucky enough to get selected, but the host hassled him about his name, eating into his precious air time. In desperation, he blurted out that "Yacov Maza" was a joke, and his real name was Jackie Mason. In what may have been his one and only capitulation to antisemitic pressure, Maza became Mason for the rest of his public life.

After he graduated from Yeshiva, Mason moved to North Carolina to work as a rabbi. At the same time, he continued to book gigs as a comedian, traveling widely to perform, living a divided life. When his father died, he decided to turn to show business full-time. "I wasn't comfortable being a rabbi," he wrote in his autobiography. "I wasn't that religious, which is a handicap in that profession." Returning to the Borscht Belt, he took a job at one of the top resorts, the Concord, where he pulled double duty. On Friday nights, it was "Thou shalt not kill." On Saturday nights, he did his act and killed.

Honing his skills in the Catskills, Mason started to get better reviews, but he couldn't get bookings elsewhere. Club owners refused to hire him, objecting to his accent. He was too Jewish, they argued, for their non-Jewish audiences. Sometimes they didn't say so directly, but he knew what they meant when they said he was "too ethnic" or "too urban."

The strongest objections, curiously, came from Jewish bookers. American Jews had so internalized the antisemitism of the dominant culture that they became vicious in their self-censorship. Mason received horrible letters and telegrams from fellow Jews — even from his own Jewish agent — insisting that he destroy the identity they shared. Mason refused to assimilate any more than he already had by taking an Americanized name. He clung to his Jewish identity, his accent, and his pride.

His tenacity paid off. After a triumphant appearance on "The Steve Allen Show," Mason became an overnight American success story, an immigrant who stayed true to himself and became a star, overcoming bigotry and pulling himself up by his own bootstraps.

Soon, though, Mason's pride became arrogance, and his arrogance inspired aggression. Not long after he cracked a cruel joke about Frank Sinatra's relationship with a young Mia Farrow, shots were fired through his hotel window. When the censors at CBS cut a couple of his jokes from an appearance on "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour," he sued the network for $20 million, claiming a violation of his First Amendment rights. (He was no Lenny Bruce; his rights had not been violated.) As egregious as that claim was, however, it wasn't the first lawsuit he filed against someone who interfered with his work.

That dubious honor belonged to the host of the top-rated television show of the period: Ed Sullivan. Mason logged several successful Sullivan appearances during the early 1960s. Then, during a spot in 1964, President Johnson decided to address the country right in the middle of Sullivan's time slot. That evening's program had to be shortened, and the change put Sullivan completely on edge.

A few minutes later, during Mason's set, an off-camera Sullivan held up two fingers to tell the comedian he only had two minutes left. Mason thought Sullivan's gesture pulled the audience's focus off stage, costing him laughs. Furious, he made his own finger gesture in response. He long held that he was only wiggling his digits to mock Sullivan, but Sullivan was sure Mason flipped him the bird on live television. (The tape is inconclusive.) As soon as the show was over, Sullivan berated Mason with a profanity-laden diatribe, barred him from the show, and threatened to blackball him from television altogether.

Overnight, Mason's career collapsed. Many of his bookings were canceled, and audiences for the shows he managed to keep were half-empty. He sued Sullivan for $3 million, claiming defamation and harm to his career. Eventually they settled out of court, and Sullivan brought Mason back on his show to apologize live on TV, but the damage had been done.

As if his own problems weren't enough, Mason worried about Israel's, too. By the late 1960s, Israel had been a state for two decades, but Egypt was gathering its forces in the Sinai for an attack to crush the upstart Jewish nation. In a surprise move, the Israelis struck pre-emptively, catching the Egyptians by surprise and decimating their air force. The Six-Day War had begun.

Mason couldn't join the Israeli army, so he decided to do the only thing he could instead: become a Jewish Bob Hope. Pulling some strings — Bobby Kennedy played a part — he made his way into Israel. Government officials in Tel Aviv had no use for him, so they sent him to a just-secured Jerusalem, where Israeli troops, grimy and exhausted from battle, were taking a brief respite. Mason found a corner where he could create a makeshift stage, then did his act. Unfortunately, few of the soldiers spoke English. For those who did, moreover, Mason's European Yiddish accent was undecipherable to Middle Eastern ears. No one understood his jokes. Even in Israel, Mason was too Jewish.

By the time he got home, he had become persona non grata. Clubs wouldn't book him anymore. Even the Catskills resorts thought he was too old-shul. After a dismal stage show and a failed movie, with few friends and fewer opportunities, Mason thought his career was kaput.

A decade later, however, the comedian who refused to give up his Yiddish accent had his career resurrected by two geniuses whose legendary character — the 2,000-year-old man — spoke the same way. First, Carl Reiner cast Mason in Steve Martin's film "The Jerk," and then Mel Brooks included Mason in the Spanish Inquisition sketch in "History of the World, Part I."

Reintroduced to American audiences, Mason parlayed the exposure into a one-man show, "The World According to Me," which made it to Broadway in 1986 and earned him a Special Tony Award. In 1992, he earned an Emmy Award for voicing Rabbi Krustofsky on "The Simpsons." Over the next several decades, he made regular appearances on Broadway and cable television. His bona fides as an early supporter of Israel and as a proud Member of the Tribe endeared him to Jewish audiences.

Despite his second-chance successes, the bitterness of his early years intensified. His muscular Jewish pride transformed into a poisonous stew of exclusionary Zionism. Racist jokes in his act grew uglier. Most notably, in one performance he used a common Yiddish slur — the rough equivalent of the N-word — to refer to Barack Obama. Years earlier, he had used the same term to refer to New York City mayor David Dinkins, responding to criticism by saying "anybody who calls me a racist should be shot like a horse in the street." He seemed to have learned nothing in the intervening decades.

By the end of his career, Mason's work as a comedian took on a darker tone: the white rage of contemporary politics. He started to use comedy as a bludgeon, wielding it against whoever was in reach, and his commentary on conservative platforms grew completely unhinged. In a video for World Net Daily, he referred to Nancy Pelosi as "a deranged pig in heat," suggesting that "Democrats should be tortured, and deserve to be tortured." As if to demonstrate how completely out of touch he'd become, he told TMZ he believed that "If it's a racist society, the White people are the ones being persecuted."

Given all of that, you may not be surprised to learn that Mason, a longtime acquaintance of Donald Trump, supported Trump's candidacy and his administration. The irony of a comedian who refused to surrender his immigrant identity yoking himself to a president who was defined by (among other things) his visceral hatred of immigrants seemed to be lost on Mason. After a lifetime of making people laugh by pointing out the world's inconsistencies, as any good comedian does, he clearly could no longer see them in himself.

Shares