On July 24, Kurt Suchman, a 26-year-old freelance writer living in Seattle, started to drink a seltzer that they couldn't taste.

"I tried another seltzer, and I was like, 'okay I can't really taste it,' and then I pulled out a jar of horseradish and shoved my nose in it," Suchman said. "I was like, 'I guess I can kind of smell it,' but at that point I was definitely a little freaked out."

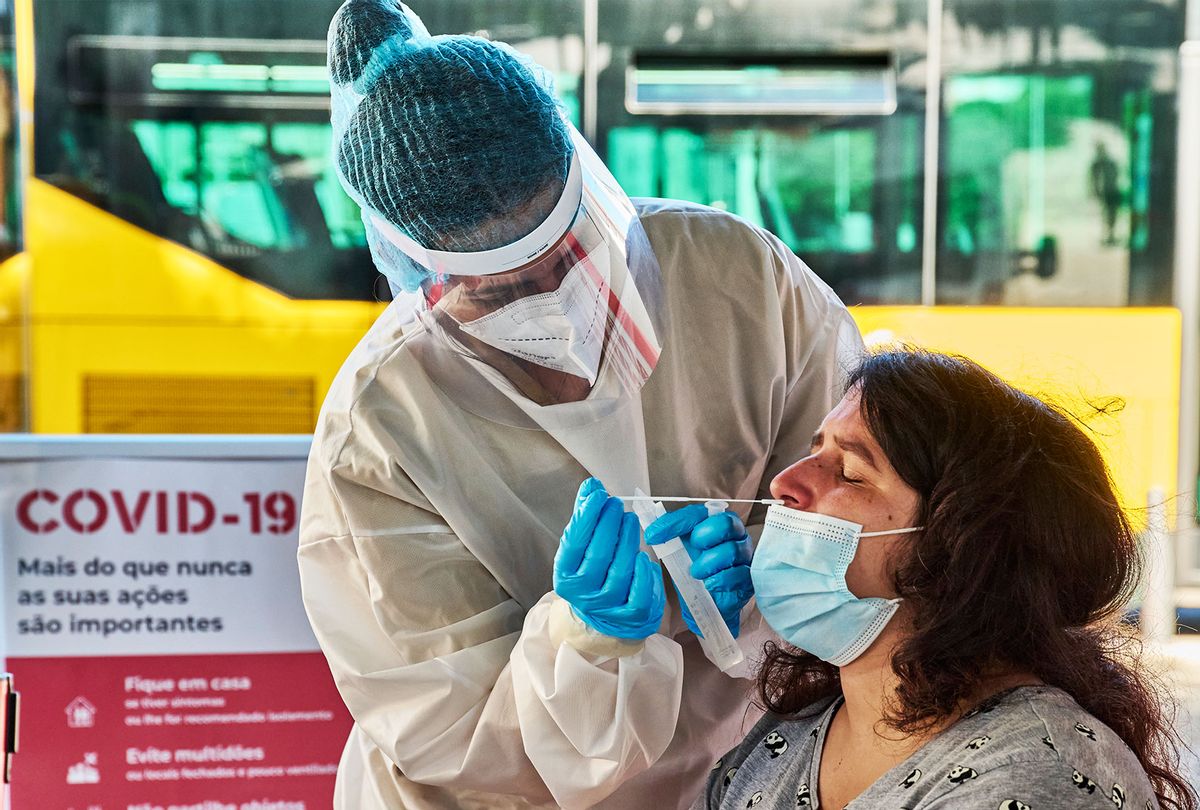

Suchman made an appointment for a COVID-19 test the next morning, which is when they started to feel "feverish." Eventually, their test results confirmed what they expected: Suchman had COVID-19, despite being fully vaccinated in May with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Suchman racked their brain trying to figure out how they got it. Suchman had not been in proximity of anyone with symptoms. Had it happened when Suchman traveled to Arkansas for a family emergency? Or perhaps at karaoke night?

"I haven't really been able to pin down where it's from," Suchman said. "The one thing I really want to know is what I can do to avoid it better next time."

Suchman compared the experience to a cold or a "24-hour flu." Yet contracting a virus for which they were vaccinated, and the unknowns surrounding transmission, stoked confusion and fear. Salon interviewed Suchman in the middle of their isolation.

It is likely that by now either you or someone you know has contracted a breakthrough COVID-19 case, the term for an infection that occurs despite vaccination. Breakthrough cases are becoming more frequent, particularly as the ultra-virulent delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads across the globe.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), breakthrough cases were always expected to occur in small numbers, as no vaccine is 100% effective; the highest efficacy rate of any of the COVID-19 vaccines was 95% when they were originally studied in 2020 and early 2021. That number has diminished as more mutations have sprung up. Indeed, according to some studies, the three available COVID-19 vaccines are less effective in preventing infection from the delta variant due to its unique mutations.

Fortunately, all three vaccines are still very good at protecting against severe illness and death — meaning that if you do have a breakthrough infection, it will very likely be mild.

Still, there are no guarantees in life, nor in health. According to the CDC, 1,141 people with breakthrough cases have died; curiously, 26 percent of those deaths were asymptomatic, or the deaths weren't entirely related to COVID-19. As of July 19, 2021, more than 161 million people in the United States were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Unfortunately, there is no solid estimate of many breakthrough cases are mild, like Suchman's was. According to ABC News, the CDC estimates 153,000 symptomatic breakthrough cases, which is still a small fraction (less than 0.1%) of the fully vaccinated population. The most common symptoms reported among those who have breakthrough cases, according to the ZOE COVID Symptom Study, are headache, runny nose, sneezing, sore throat and loss of smell.

If a vaccinated person experiences any symptoms of COVID-19 listed by the CDC, the public health agency recommends getting tested and isolating from others until a result is received. If the test is positive, an infected vaccinated person should isolate at home for 10 days. According to the CDC's guidelines for the fully vaccinated, those infected with the delta variant can spread it to others.

The existence of breakthrough cases doesn't mean that vaccines aren't doing their job, experts say. In fact, merely coming down with a mild infection rather than a severe one is often evidence that the vaccine is doing its job in helping your immune system fight the virus. Since the existing vaccines were developed to combat the alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2, it makes sense that they're not as effective in combating the delta variant, whose mutations have shown to some extent to evade the immune response from the vaccines. Yet all the COVID-19 vaccines are mostly able to stop the infection worsening.

"In a vaccinated person, what will happen is that we already have cells that very specifically recognize an infected cell, and can aggressively target that infection so that the virus can no longer replicate," said Dr. Nicole Baumgarth, a professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at University of California–Davis. "Even if we cannot stop the infection from happening, [the vaccine] stops it very early in its tracks; the less virus replication you have, the less symptoms you will have, the less disease and it gets easier for the immune system to mop up the little bit of virus."

Signs of infection, like a fever, develop when the immune system has been activated to fight it.

"Some of the signs of disease are actually signs that the immune system has been activated," Baumgarth said. "That's one response to the body to fight the viruses, to increase the temperature."

Baumgarth said it is in fact accurate to think of a breakthrough infection as a "booster shot." However, Baumgarth would not advocate for people to purposely expose themselves to the virus. Yet a mild breakthrough case does build one's immunity against the virus.

Of course, given the possibility of spreading the virus further, it is best not to get infected at all.

In mentally preparing for the possibility of breakthrough case, Suchman advised caution, even among the vaccinated.

"Even though the symptoms have been pretty mild, you still don't really want to be sick," Suchman said. "It just feels extra gross now, like with all the work that we've been [doing] for the past year.

Shares