Voting rights have not had a good summer. First, a Senate filibuster frustrated congressional efforts to pass the "For the People" bill. Then, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, further eviscerated the Voting Rights Act, not only upholding certain provisions of an Arizona law making it more difficult to vote, but interpreting Section 2 of the Act to make future federal challenges more problematic.

These setbacks raise key questions for those concerned about voting rights, and what strategies to employ to defend and expand them.

Many Americans thought that the defeat of Donald Trump would lead to the expansion of voting rights. Good ideas in this arena would prevail and the courts might recognize that change is in order. This was not to be, and the federal landscape is not likely to improve without a watershed election in 2022 that few now see as likely. Even if the filibuster were to fall, it is not clear that progressive voting rights legislation could pass. And the Supreme Court has clearly become the conservative vessel that Trump and the Federalist Society have coveted for years.

So what is to be done? It would be a mistake to abandon Washington politics and folly to give up on the federal courts. But if we want to expand voting and change America in the process, the best places to fight are where most rules on elections are written — in the states.

The American public has placed so much emphasis on decisions made in Washington that it has lost track of what is happening in state capitals. Leaders from both political parties, however, have recognized that major victories can be won and lost in the states, and that is why we have recently seen so much activity on voting rights in these arenas.

It is commonly understood that following the 2008 election of President Barack Obama, national Republicans were so concerned about their future ability to capture the popular vote in a presidential race — Republicans have lost the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections — much less win the Electoral College, that they invested substantial resources in trying to win control of state legislatures. They were tremendously successful in 2010 and took control the redistricting process in key states, a crucial element in solidifying a congressional majority until 2018.

Now, state legislatures and governors across the nation are locked in historic struggles about the future of our right to vote. In the first half of 2021, more than 2,200 elections-related bills were introduced. As of June 21, some 17 states had enacted 28 new laws restricting access to the vote.

Not unexpectedly, Republican-controlled bodies have been the most aggressive in their actions, embracing a wide variety of limitations that will make it harder to vote, and eliminating provisions created during the pandemic that enjoy widespread support.

After record numbers of voters cast absentee ballots in Georgia's November election — about one-quarter of the state's 5 million turnout — the Republican-controlled legislature passed new voter ID requirements for absentee voters, thereby increasing the burden on more than 272,000 registered voters who don't have a driver's license or state ID on file with election officials. The legislation also targeted "mobile voting units" that proved effective in increasing turnout in Fulton County (Atlanta), a locality where Biden garnered 73 percent of the vote. Lawmakers passed a measure to prohibit localities from using these buses in the future, except "in emergencies declared by the Governor." Finally, new Georgia law now prohibits election officials from mailing absentee ballot applications to all voters, as Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger did during the pandemic, and reduces the time prior to an election when a voter can request such a ballot. The Georgia measures are now under attack by the U.S. Department of Justice, which claims they are illegal under Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Florida passed similar provisions to those adopted in Georgia, most targeting the ease of mail-in voting.

After similar efforts were foiled in Texas by a last minute Democratic quorum-breaking walkout in May, the governor conveyed a special session to ram through the proposals. These states share a common characteristic — both houses of the legislature and the governor are controlled by the same party.

In recent years, we have grown accustomed to measures like these. Some even can appear relatively benign — until one assesses the practical impact of their implementation. Requiring a person to produce an ID in order to vote, for example, while it enjoys substantial popular support, disproportionately impacts minorities and the disadvantaged who find that they do not have the ID required by the law, until it is too late.

In many states, new measures appear even more brazen. The Arizona legislature recently declared war against elected Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, passing measures to take away her powers and transfer them to the Republican attorney general. Georgia Republicans took aim at Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger for failing to adhere to the Big Lie, replacing his oversight of elections by creating a new chair of the State Election Board appointed by the legislature. At least five states are now pursuing a new type of partisan election audits, conducted not by election officials but by private entities. Taken together, the proposals are so significant that it has prompted one recent study to declare the measures to be a "democracy crisis in the making."

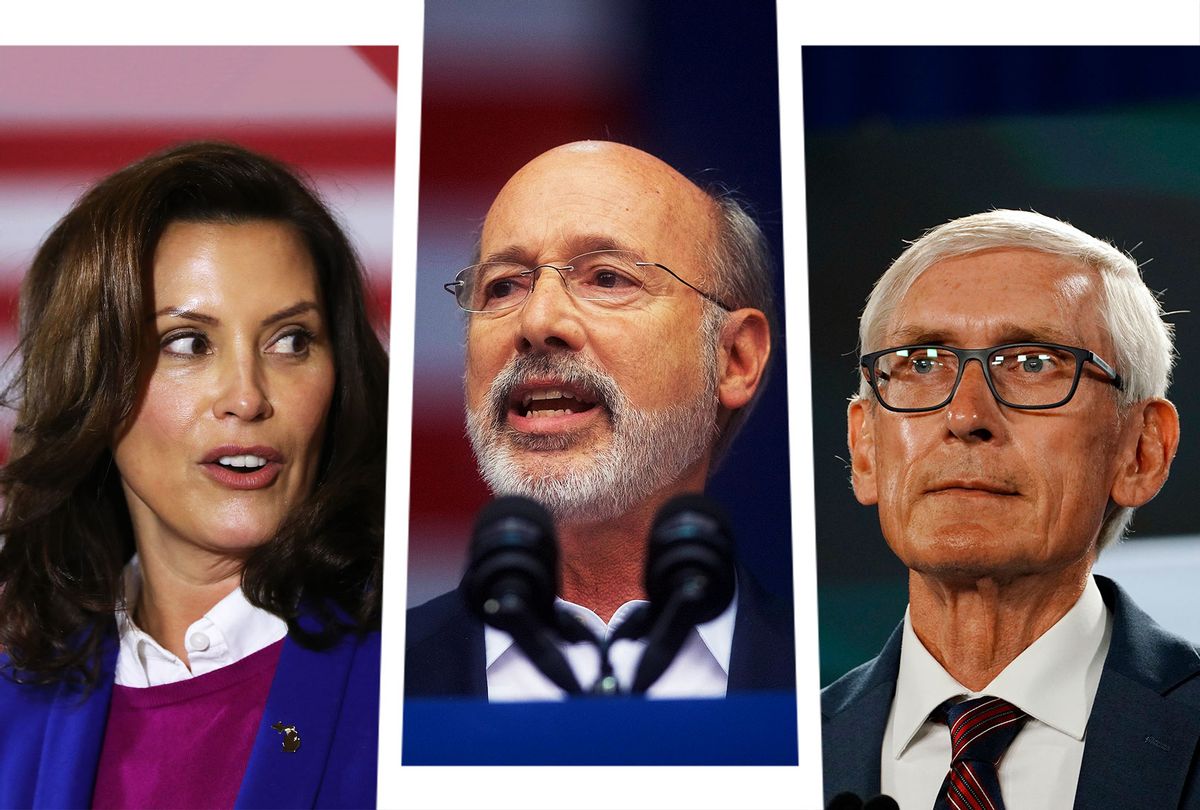

In many instances, the only barrier to these draconian measures have been Democratic governors. Both Wisconsin and Michigan have passed restrictions on voting which have been or will be vetoed by Gov. Tony Evers and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, respectively. Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf not only vetoed a Republican-backed bill that would have established new voter ID requirements, created new barriers to absentee balloting and eliminated ballot drop boxes in the state, but also struck a budget measure to enable so-called voting audits modeled after the controversial and widely criticized operation being conducted by private entities in Arizona.

Voting expansion has occurred in several states. Maine recently added student IDs from authorized colleges to the list of acceptable forms that voters can use when registering to vote. Louisiana, after a surge of early voting in 2020, now provides additional time for voters to exercise this option. In Kentucky, following record-high voter turnout in 2020, no-excuse absentee in-person voting was extended to three weeks prior to elections. But the most dramatic change comes from Virginia. Known as a ruby-red state for almost two decades, the Commonwealth has now become decidedly blue. Not only has the state chosen Democratic candidates for president each year since Obama in 2008 and elected Democratic governors in four of the last five elections, 2019 brought Democratic control over both the House of Delegates and the State Senate, something not witnessed since the dawn of the century. And the state has now adopted some of the strongest voting provisions in the country. Lawmakers proceeded to repeal draconian voter ID requirements, expanded early voting to 45 days and enacted automatic registration. In addition, Virginia became the first Southern state to enact a "pre-clearance" requirement similar to one that existed under the federal Voting Rights Act before it was stricken in 2013 by the U.S. Supreme Court in Shelby v. Holder.

Most of the push for voting rights targets state legislatures. But other options are also available. Advocates should look to state constitutions, almost all of which explicitly recognize the right to vote. Such provisions exist even in states that are not typically viewed as havens of liberalism. Some 12 states, including Missouri, Tennessee, Wyoming and Arkansas, declare that elections shall be "free and equal." Indiana, Kentucky, South Dakota, Pennsylvania and Oklahoma are among 30 that include a provision that "no power, civil or military, shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage."

By contrast, the U.S. Constitution does not include such provisions, and federal court decisions have concluded that our founding document only protects against governmental actions that violate provisions such as the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Consequently, federal jurisprudence has generally permitted states to impose burdens so long as they are not overly severe or overtly discriminatory. In addition, more than 25% of federal appellate judges have been appointed by Trump, and a recent study shows these appointees evidence a pattern of ruling against voting rights plaintiffs. By contrast, swing states like Colorado, North Carolina and Pennsylvania currently have Democratic majorities on their state supreme courts. Some legal scholars argue that it is time to marshal these provisions in service of the most foundational right in our democracy.

A recent case from New Hampshire illustrates how strong language in a state constitution can protect voting rights.

In early July, the state's Supreme Court unanimously invalidated 2017 legislative measures that required newly-registering voters to provide proof of residency before they could cast a ballot, finding them to be "unreasonable burdens on the right to vote." The decision was based on the state's constitution, which includes language that "All elections are to be free, and every inhabitant of the state of 18 years of age and upwards shall have an equal right to vote in any election…." State courts in North Carolina are now considering whether its constitution will serve as the basis for overturning a restrictive voter ID provision of the law. Pennsylvania, which has included the "free and equal" provision in its constitution since 1789, has extensive jurisprudence protecting the right to vote under state law. Some states have constitutional clauses that are easier to use than others, but chances of judicial victories at the federal level are increasingly problematic.

Beyond the courts, many states give citizens the ability to place proposals directly before the voters through what is called "initiative petition." Twenty-four states have the initiative process. Of those, 18 allow initiatives to propose constitutional amendments and 21 states allow initiatives to propose statutes. For those who support the expansion of rights, citizen initiative is another avenue worth exploring. We have seen the power of citizen initiatives most recently in the number of ballot initiatives that have made recreational marijuana legal in several states, even in the face of legislative resistance. In 2020, constitutional amendments were passed in California and Florida through direct ballot initiatives that allow felons the right to vote upon completion of their sentences.

In the final analysis, the best way to protect and enhance voter rights is at the ballot box. But other means — particularly in the states — also exist, and advocates should not be shy about using them. Only our democracy is at stake.

Shares