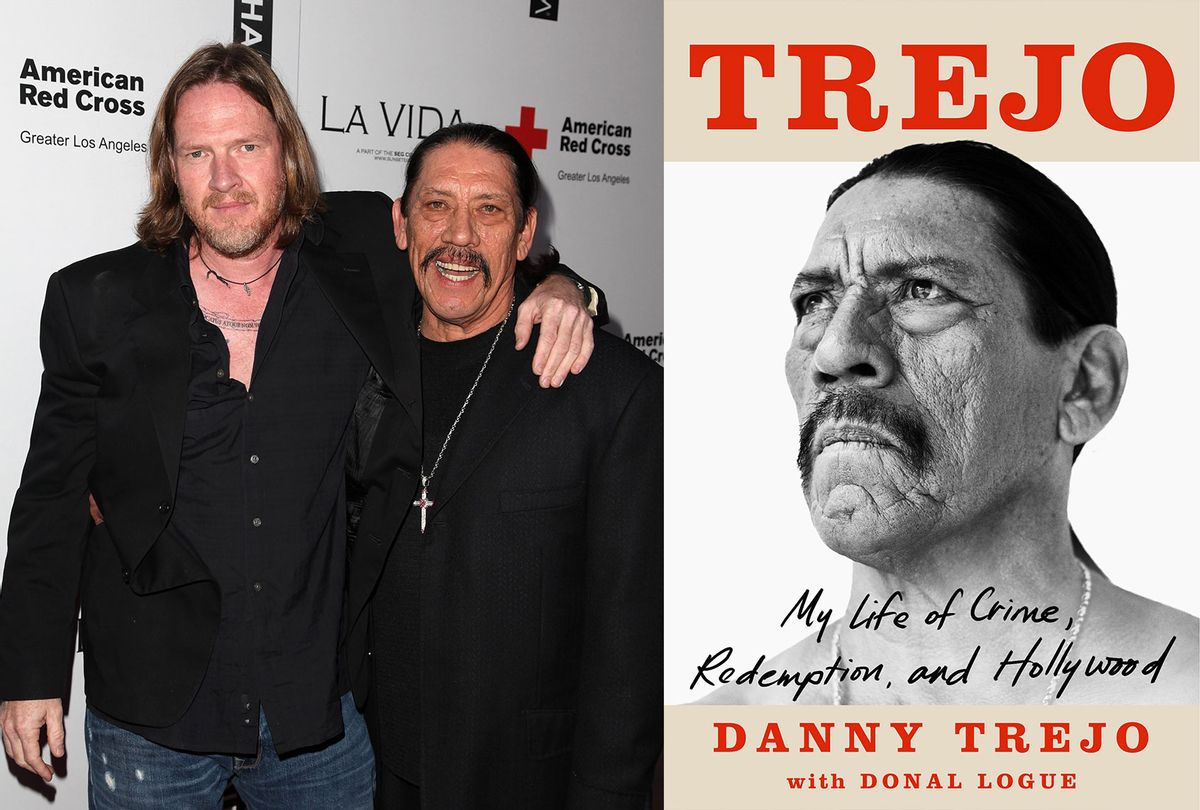

If I had a dollar for every time a producer, director or actor tried to use my reckless background as a tool to add validity to their film or television show about "the ghetto," I would be a very rich man. The problem is that I have too much integrity to sell out my neighborhood, my family and myself, which is a rarity. I know that in America, everybody with money thinks that everything is always about money –– and it's not. If my community knew that I was a part of a project that didn't honor our neighborhoods in the right way, I would not be able to come back home. Legendary actor Danny Trejo writes about the same kind of community loyalty in his new memoir, "Trejo: My Life of Crime, Redemption and Hollywood" (Atria, July 6).

Most know Trejo from the dozens of movies and television shows he starred in, including "Heat," "Machete," "Anaconda," "Breaking Bad" and "Spy Kids" to name a few, but that is just the second half of his life. In "Trejo," Danny writes about his time in prison with Charles Manson, struggles with addiction, struggles with personal relationships, struggles with his kids, his road to recovery, financial hardships that arose during his career, and how he became a successful businessman, while feeding the homeless, surviving a stroke, meeting Obama and pushing for prison reform. Yes, this man has a story. Trejo's past has gained him access to work on the kinds of exploitative movies I mentioned, and he walked away because he has that same kind of community loyalty. I took a long stroll with Trejo down his amazing past on a recent episode of "Salon Talks."

You can watch my "Salon Talks" episode with Danny Trejo here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

A lot of people who studied your work or who saw you in films over the years, and we saw interviews that we'd get like little bits and pieces of you, but this goes in. It's a lot to unpack here, so just to kick it off, can you just tell us how the project came about? What made you sit down and say, "You know what? It's time for me to put my story out."

You know what? I did a documentary called "Inmate #1," and everybody thought that it was "Inmate #1" because I'd done time. I said, "No, no, no! That's 'Inmate #1' because that's the first five years of my acting career." I played Inmate No. 1, a bad guy and Chicano dude, mean dude with tattoos. I never even had a name, so that was where I got the name.

Then, my kids' mom, she read it. She saw the documentary. She said, "It's very nice, Danny. That's like you were a bad kid, you went to prison, and now you're a good guy. It's like, what about your mom? What about your dad? What about the things that made you?" I said, "Well, that's their story. It ain't got nothing to do with me." She said, "Dan, why do you think you've been married four times? Why do you think you've been divorced four times? Why did you get children with women you weren't married to? How come you couldn't trust a woman?" I said, "What are you talking about, man? I was with you 10 years. You didn't trust me to go to the market!" It's really funny. No woman's ever done me wrong. If you read the book, you kind of understand why I didn't trust. So, we wrote it and, when she read it, she, and this is the lady who's been with me 40 years, not together, but she's the mother of my children, so you can't get away from baby's mama. So, when she read it, she says, "You know what? I feel like I'm talking to you," and that was it. We got it because that's me. What you hear is me.

One of the best part of the book and I think something that people are really going to be inspired by is the battle that a lot of us men face, right? We're from two different generations, but we suffer the same way when it comes to vulnerability.

You said it perfect. I don't think I could've done anything without Donal Logue. I mean, I've been in AA. I've done inventory after inventory, I've been sober 52 years, but I would still write I had a good day and this is what happened today and when I was young, but nothing about my mom, my dad. So, I don't think I could've done that without Donal, without somebody that I really trusted. When I started, boom! It just came out.

It was funny because, while I was writing it, my son had written a movie called "From a Son." So, I'm already all emotional anyway, and he's showing me these baby pictures of him, "Look, dad. Remember when I hurt my arm?" and all these baby pictures. I had baby pictures in my trailer of him. You know what I mean? When it came time to do this crying scene, I wanted to do it like John Wayne, "OK, pilgrim." I had all these pictures, and then Sasha, the girl that we cast as his girlfriend, I asked her, "Did you kill my son?" We're in the desert. It's freezing cold and she goes, "No! I loved him. He was my only friend," and she started bawling. I broke loose. John Wayne, my ass! I had boogers, that kind of crying nobody's supposed to see. That way when you're alone at a family movie or some shit. You know what I mean, but I couldn't stop, man. When he finally said, "Cut", the whole crew was crying. My son, little shit, goes, "Nice acting, dad." I go, "Shut up! I'll put you on timeout!"

Something that resonated with me on a personal level was, I just had my first kid a year ago. I got a baby girl.

I think you're going to learn more about women than you've ever known raising a daughter. Honest to God. I learned patience. I got patience from nobody but my daughter. You know what I mean? She was three years old. I was a single parent. We'd jump in the car and she goes, "Daddy, I forgot my purse." I go, "You're three-years-old! You already got a purse?" She would just give you that look. They're born with that look. That look, it's a kind of a, "You an idiot and if you don't do that, I am going to be a brat the rest of the night." So, I go up and get her purse, and that purse don't match her shoes. She's three-years-old! I got to take her up to pick a purse. I swear to God, and then you love doing it. In the middle of the night, you wake up laughing at some of the s**t she does. You know what I mean? It's like there's no love like a dad for his daughter. We used to sit on the couch and talk about boys stink. The boys would be on the other couch.

It's a blessing. I think the part that's going to resonate with a whole lot of people is when you talk about your time incarcerated. One thing I wanted to ask you was, as we're moving into this space where society is starting to care more about returning citizens the way they should, what are some of the biggest misconceptions that people on the outside have about people inside and people returning? What do they need to know from you?

Our systems for prison are broken, first of all, OK? You start with a district attorney. We got a three-strike law. That took all the power away from the judge and gave it to the district attorney. So, no matter what I do, I'm going before a guy that's got the whole game. I'm going before a district attorney. Now, he's going to make a deal because district attorneys don't stay district attorneys if too many people go free. That's our system. So, it's his job to put people in jail. Guilt, innocence don't have a damn thing to do with it. It's numbers, OK? Now, I would estimate, and it's a pretty good estimation, that 10% of the people in the California prisons belong in prison. I was one of the ones that belonged in prison until I had a life-changing experience, and it's like, basically, I knew most of the guys that belonged in prison. So, that means 90% of the people in prison could've been dealt some other way. Non-violent drug offenses, OK? Now, I know people got away with 13 kilos, 14 kilos of cocaine, and I know people that are in prison doing eight, 11, nine, 12 years for 3 grams of cocaine, all right? I know people that are doing five years for paraphernalia, OK? So, we say, "Wait a minute. Something is wrong here. Something is definitely wrong."

My best friend got 30 years for a non-violent drug crime. He's 15 in right now.

My little cousin went to the joint when he was 16 years old, bad second-degree murder. He was supposed to go to prison.

Gilbert, right?

Yeah, Gilbert. Now, that's my uncle's son. I've been trying to get him out, so I talked to everybody, just literally everybody, all the way to the governor. We got a law passed that if you're a juvenile, you can still come up for parole because when you have a life sentence, every 15 years you come up for parole. Now, you're a different person when you're 16, when you're 30. You're a different person, whether you're in prison or not, you're a different person. You might be crazy as a loon or you're better, but there's an evaluation. So, now, we got Gilbert out. It set a precedent for a law. Now, 4,500 people that were sentenced as juvenile have got out because of that law. I get stopped on the street by guys that did 30 years. "Man, thank you, man. Thank you. You got Gilbert out," my nephew. "You got him out. I got out on that same law." I said, "I'm so proud of that, man! Gilbert, his name's in the law book, Gilbert Trejo. First, he went to work as an electrician on the Rams stadium. Go, Rams! I know you're from Baltimore, I know, but go, Rams! We finished the Rams stadium, so he went as an electrician over to LAX. You got to put down three references so, as soon as he put down the references, the feds grabbed him, says, "You got three ex-felons, Danny Trejo, Mario Castillo, and Salvador Saldana. They're all exes." Thank God that the powers that be, [Gavin] Newsom and everybody else, our governor, they knew we were doing good so, right now, Gilbert's working at LAX. He's doing great.

That's another story that made me really, really happy when I finished the book. So, people know Danny Trejo, the actor. People know Danny Trejo, street guy. People know Danny Trejo, the businessman. A lot of people don't know Danny Trejo, the firefighter. Let our viewers know a little bit about your days as a firefighter because I really want them to feel the storyteller?

You know what? Silliest thing in the world is standing there throwing a shovelful of dirt at a 80-foot flame, feel like a complete idiot, but enough shovelfuls, you'll put it out. I'd been fighting fires. I went to camp when I was 16 years old, and I was fighting fires. Then, when I was in the joint, they sent us to fight a fire in Sacramento and all the fires that were up there. It was funny. These old ladies would come out in the middle of the night at 2 o'clock in the morning. They come up, "Here, son. Would you like some coffee?" and then they'd wink. So, old lady, 108 years old, giving us a shot of whiskey in a cup of coffee. It was beautiful. That's what I've done. I've fought fires. I've done everything for the State of California.

I think one of the things that's really inspirational is the time you spent as a counselor and helping people with their sobriety and becoming clean. How important was that work to your own redemption and recovery?

We still do that. I still do that. I still work for Western Pacific Med Corp. My CEO, Mark Hickman, that guy lets me do whatever I got to do. The way God works is so funny. I met Mario Castillo in 1991. I was doing "Blood In Blood Out." We were doing it in San Quentin State Prison. He was a resident. He refused to be called an inmate. "No, I'm a resident." "Yeah, well, you're still busted, sucker!" We talked and we made friends.

Then, eight years later, he came out and he was trying to stay clean and stuff, and then he got a job working in recovery. Then he got sick. When he got sick, he couldn't work and lost everything. Come stay with me, so he stayed with me. That guy saved my kids' lives. Do you understand? I get a call. I'm in Germany. I get a call, and one of my son's friends, "Man, Gilbert's dying! He's over here in this crack house. He's got that ATM card." People are like, "Hey, come on." I said, "S**t!" I called Mario. "Mario, you know what? I got to find Gilbert, man." Now, the bodyguard goes because Mario took a bodyguard with him, pulled up in front of a crack house that's got two guards out in front. The bodyguard says, "Let's call for backup," and Mario was, "Man, f**k you!" Crashed, kicked in the door and grabbed my son, carried him out, threw him in the car. "Let's get the f**k out of here!" My son, "Hey, Dad. I'm OK." I got home. We took him to rehab. My son's going on eight years clean right now.

That's a blessing there.

I'm telling you, but that's the way God works. I didn't know that, in 1999, this fool who thought he was a resident in San Quentin was going to save my son's life.

You mentioned "Blood In Blood Out." Talking about "Blood In Blood Out" and "American Me," what was happening at that time? And I really, really, really like when you said, "There's no poetic license when you're pissing off the wrong people." I would like you to talk about making the transition from being a guy who still has all these connections, but being brand new in the industry and staying loyal to your community versus just jumping in front of whatever Hollywood puts in your face?

You know, it's so funny that I told the director, Edward James Olmos, "You can't do this. You're disrespecting the wrong people. You're being a fool." He goes, "No, no!" You're not dealing with theatrical people. See, that's the thing. I needed an English literature major from the streets. Well, he'd have been perfect. You'd have been perfect. I like talking to you. You would've been perfect. It's like, here's this dude was never in a gang, never from the streets, started acting when he was nine. So, all of a sudden, he's portraying this bad guy. When they showed that this guy, the leader of the mob who's raped, I would say, "Wait a minute. You're disgracing this guy's family. You're disgracing everything." He was, "Well, theatrically, doesn't it come . . ." "You don't understand theatrical, sucker!" He wouldn't listen because people got it in their mind that, "I know more because I've played a bad guy." Well, these guys ain't playing, and it was straight out. Eight people killed in Folsom that had taken part in that and four people killed on the streets. I remember one time, Edward was trying to say, "No, that wasn't because of the movie." Big Donald, one of the leaders was standing right behind him, and he goes, "Excuse me, Mr. Olmos. Yes, it was." The whole room went ice cold.

When I walk into a club and there's like five or six Mafiosos standing, everybody knows who they are. It's so funny. When they're in the club, there's like a secret wall around them. They're there, they all got two girls. There's a moat around them that nobody gets close to. It's so funny, not because they're acting tough, but because the respect that people have for bullets. When I walk in, they'll go, "Uh!" They'll all stand up. "La Onda" because that was the name in "Blood In Blood Out." They respect the s**t out of us. It was funny because the guys that worked on "America Me," the actors called me and said, "Danny. We understand you. Are we OK?" "Yeah, yeah, yeah. You ain't got nothing to worry about. You were workers," because, when Joe Morgan called me and asked me what was I going to do, I said, "I'm going to do 'Blood In Blood Out.'" He goes, "Oh, yeah, yeah. That's the cute one." Now, we're doing a movie about murders, killers. That's the cute one, but it was cute because we weren't saying Mexican Mafia. You know what I mean? So, I told, "They ain't got nothing." Joe Morgan told me, "You can do that other one." I ain't doing that one. I know. I know respect. I've never lost respect of that both ways.

Some of the things that I wasn't expecting was reading about you coming across Charles Manson and George Jackson in the joint?

You know what? Now, Jackson, he was bad. There was nothing phony about George, but when I met Charles Manson, he wasn't the guy you saw on TV with that beard and the swastika. That wasn't him. When I saw him, they were getting ready to do him in the county jail. He was just a skinny kid, and he was so poor he had a string tied – his pants were being held up with a string because he didn't have a belt. He couldn't have done that to those girls, like on the North side of Philly or in Compton or in East LA. He was in Haight-Ashbury with some broken little girls from Broken Elbow, Louisiana somewhere that were abused there, came out to Frisco and were abused there. George Perry, a good friend of mine, who was a pimp from Oakland, he said, "Man, everybody was running them girls crazy. Everybody was using them." So, when he showed up, they're looking for a Messiah, "Be my daddy." When we saw him on TV, we thought it was funny. Look at this guy. We protected this fool.

So many people out there are saying, "I used to run with Danny Trejo" from the early years. What do you think those people say now when they see you now? If they get a chance to walk through LAX and here you walk in?

Listen, my daughter came into LAX with three of her friends, right? She was staying in Ohio and flew in. The first thing they heard was, "Hi. I'm . . . Hey, there's your dad!" Everybody was asking her for an autograph.

What would you say to young artists who feel like they just get caught up in the world where they're scared to just jump out there and do what they love because of whatever reason why people walk away from things?

The advice that was given to me, the best advice that was ever given to me was, "The whole world can think you're a movie star, but you can't." It's like I've watched kids that, because they're doing, "Wow! I'm in the movies," then all of a sudden, they think they're something. You got to think like, "I'm a house painter" or, "I'm a plumber" or, "I'm a electrician" because that's all it is. It's a job. Yes, it's a job with a lot of perks, but you got to fight that battle. It's a battle. It's a battle because Hollywood is meant to seduce you, and it's meant to seduce you so they can get rid of you. It's meant for you to think you are so good that you're so big a problem, they can get you out of there. You look at everybody that became a movie star. They're gone, but you talk to Robert DeNiro, you call him a movie star, he'll go, "No, no, no. I'm an actor. I'm a working actor." Do you understand? Movie stars are dicks, OK? They suck.

Shares