If the thought of an extinction event–level asteroid hitting Earth keeps you up at night, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has relatively good news for you: the chances of asteroid Bennu striking Earth are higher than previously thought, but probably not high enough to lose sleep over. That's partly because we are getting better at spotting and calculating asteroid trajectories, but also because NASA is soon to test technology that could divert a threatening asteroid decades in advance of impact.

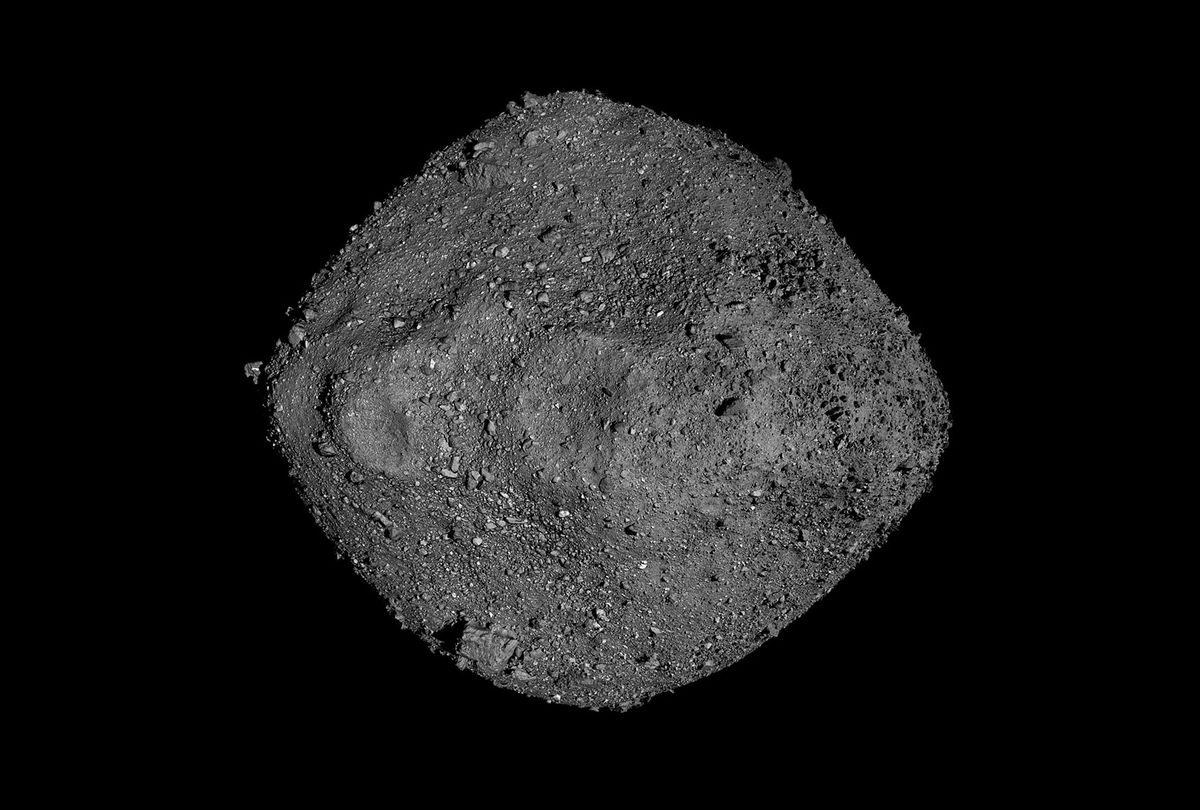

This week, scientists published an updated estimate related to the trajectory of this particular asteroid of concern, Bennu, in the journal Icarus. Bennu's estimated chance of hitting Earth prior to the year 2300 is now 1 in 1,750 — slightly greater than the previous probability of 1 in 2,700, but still quite low. NASA discovered Bennu, a carbonaceous asteroid about 500 meters in diameter, in 1999, and has been keeping track of it ever since. In fact, it is one of the two most hazardous known asteroids in our solar system, though its likelihood of hitting Earth is still pretty slim.

Yet the news about the updated estimate isn't of note due to the revised probability, but because the technology used to calculate it is believed to be the most precise estimate of an asteroid's future trajectory ever calculated.

Using NASA's Deep Space Network and state-of-the-art computer models, researchers were able to further minimize any uncertainties about Bennu thanks to the observations made by NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft, which is now en route to return to Earth after studying Bennu up close.

"We carry out this endeavor through continuing astronomical surveys that collect data to discover previously unknown objects and refine our orbital models for them," said Kelly Fast, program manager for the Near-Earth Object Observations Program at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "The OSIRIS-REx mission has provided an extraordinary opportunity to refine and test these models, helping us better predict where Bennu will be when it makes its close approach to Earth more than a century from now."

As Salon previously reported, the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft also made headlines for collecting samples on Bennu, which scientists believe may have had water on its surface earlier in its history. This is all part of NASA's Planetary Defense group, whose sole purpose is to discover and monitor asteroids and comets that might pose a risk to Earth.

Data collected by OSIRIS-REx gave researchers an opportunity to test their models and calculate when Bennu would be most likely to hit Earth. Indeed, the data from OSIRIS-REx allows researchers to "test the limits of our models and calculate the future trajectory of Bennu to a very high degree of certainty through 2135," said study lead Davide Farnocchia, of the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), in a statement. "We've never modeled an asteroid's trajectory to this precision before."

Specifically, researchers estimate that Sept. 24, 2182, will be the most significant single date in terms of a potential impact, with an impact probability of 0.037 percent. Even though the odds are low and no one today will be alive then, Dr. Ed Lu, Executive Director of the Asteroid Institute, said Bennu isn't a threat to Earth precisely because of our careful tracking of it. Lu is more concerned about are asteroids that aren't on NASA's radar.

"Most of the asteroids in our solar system that could do great damage should they hit the Earth are untracked," Lu said. "Those asteroids are large enough to destroy a city should they hit, but 99% roughly, of those, are untracked — zero data."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Lu compared tracking Bennu to tracking a hurricane, as the models are somewhat similar given the constant variability. Just as weather forecasting has come a long way, astronomy advancements over the last several years — including new telescopes and relevant missions, like the Japanese Space Agency's probe currently exploring the Ryugu asteroid — are preparing the world for more precise measurements when it comes to asteroid tracking. In general, asteroids have been notoriously hard to track.

"They are difficult to track because they're orbiting the sun just like the Earth . . . their distances can be quite far from the Earth, and they are small and dark," said Lu. "But the issue behind tracking is both not just seeing them, but seeing them often enough so that you can accurately determine the trajectory."

Scientists are already testing technology that would essentially nudge a potentially dangerous asteroid away from Earth. One mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft, is expected to launch sometime after November 24, 2021, from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. Once in space, the spacecraft — a joint project of NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory — will travel for ten months to reach the Didymos asteroid system. The spacecraft will then literally ram into Didymos' smaller asteroid moonlet, Dimorphos, to change its orbital path.

"DART will change the orbit speed of Dimorphos by a little bit less than a millimeter per second," said Andy Rivkin, DART investigation team co-lead at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). "That may not seem like a huge change, but it will be easily measurable compared to Dimorphos' average speed around Didymos."

Rivkin said in the case of a real life emergency in the future, scientists would possibly "change the speeds of asteroids a bit more."

"But our best information favors doing a gentle tap applied decades ahead of time to avert an Earth impact when possible, rather than a forceful shove applied at the last minute," Rivkin told Salon.

Later, the European Space Agency's HERA mission will conduct follow-up observations to survey DART's collision, and turn this experiment into a repeatable planetary defense strategy.

"Together these missions allow us to better understand how we can protect humanity from future asteroid impacts," said Danica Remy, President of the B612 Foundation, a nonprofit whose goal is to protect Earth from asteroid impacts.

But what about those pesky, unidentified asteroids that have escaped observations?

"The best thing the public can do right now is to advocate for increasing asteroid discovery rates and to provide funding for asteroid discovery and deflecting programs," Remy added.

Shares