Harvard immunologist Dr. Bruce Walker first heard whispers of the coming pandemic while teaching a course on HIV to MIT undergraduates in South Africa. One of his students, who had recently returned from visiting family in the Chinese city of Wuhan, recounted the state of affairs in grisly detail.

As the student relayed, she had been "getting text messages from her parents saying that something really drastic is going on there," Walker recalled to Salon.

At the same time, one of his student's phones began blowing up. It belonged to Diana Brainard, at that time the senior vice president for emerging pathogens at the pharmaceutical company Gilead, and one of Walker's guests in the course. She was getting phone calls from experts asking her to release a drug called Remdesivir, to see if it would work against this new kind of pneumonia that appeared to be due to a novel coronavirus.

These were Walker's first hints that his life was about to radically change. And though the COVID-19 pandemic wasn't caused by the HIV virus, Walker knew his research could be of great use. A year and a half later, it turns out he was right: the COVID-19 vaccines, among other novel coronavirus treatments, owe a great debt to years of HIV research.

The versatility of HIV research in its larger applications to medical science is not widely known. Yet there is a glut of research into virology stemming from the intense effort, spanning decades, to try to unlock the mysteries of the human immunodeficiency virus — an effort that spans many different subfields within medicine. Hence, the decades-long fight against HIV has yielded numerous insights into fighting other diseases, and creating treatments for other conditions.

In the early days of COVID-19, the first step in defeating the virus was finding its weakness. Here, too, previous HIV research was useful. According to Dr. Michael Farzan, chair of immunology and microbiology at the Scripps Research Institute, because researchers had a "deep understanding of why HIV is a hard vaccine to make," and understood that, in contrast, SARS-CoV-2 would be an "an easy vaccine to make."

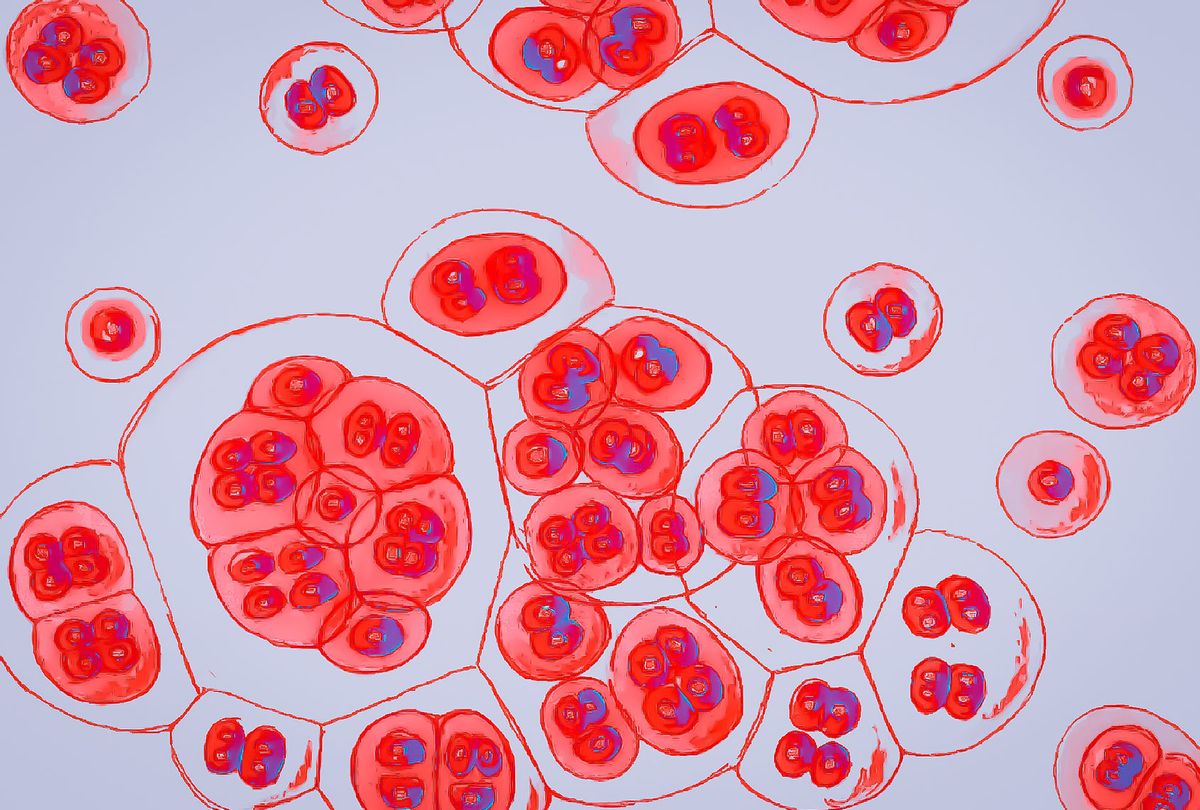

"Both viruses use a very similar kind of protein that you've seen many times," Farzan told Salon. "SARS-CoV-2 and HIV both have a glycoprotein that they use to enter cells, and that is the primary target of these vaccines. There are very strong similarities between the entry processes of these two viruses, and several other kinds of viruses including the flu, but there are also some very clear distinctions that make SARS-CoV-2 but not HIV vulnerable to vaccines that we are using now."

In the case of his own research, Farzan was able to help identify an important feature related to the ACE2 receptor for SARS-CoV-1, or SARS, as that virus is known. ACE2 receptors are specific proteins that allows coronavirus to infect human cell; they exist in SARS-CoV-2, or the novel coronavirus, too.

"The unique property is the thing that binds the receptor, not on the receptor," Farzan explained. "In the case of SARS, it is independently folded and exposed and prominent. In the case of HIV, the part that binds the receptor is sort of embedded in a canyon that antibodies can't get access to."

The fight against HIV also helped scientists develop mRNA vaccines, which were used by companies like Pfizer and Moderna to create effective inoculations against COVID-19. These vaccines use synthetic RNA molecules to train cells to produce proteins similar to those in the pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms) that you are meant to be inoculated against; this is in contrast to traditional vaccine platforms, which use a weakened or dead sample or part of the pathogen itself.

As Farzan told Salon, these vaccines are "just one of the silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic, the manner in which that was propelled forward."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

It also helped that the decades of virology research for fighting AIDS had left the government with vaccines that could immediately be repurposed to develop medicines against COVID-19.

Dr. William Haseltine, a biologist renowned for his work in confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic, as well as the chair and president of the global health think tank Access Health International, noted that "a number of different technologies were pioneered in efforts to develop HIV vaccines." "In addition," he added, "national and international vaccine clinical trial networks were constructed and operational. All were important for rapid development, testing and analysis of the safety and efficacy of COVID vaccines."

Scientists would also be able to test these vaccines on thousands of people with remarkable speed because the international network had already been created by HIV researchers. Likewise, officials found a system in place to quickly approve programs for developing new drugs — all because HIV researchers had insisted that the state have the capacity to move quickly in the event that any serious manmade or natural disease suddenly swept through the masses.

There is a long history of research against disease research helping scientists in unexpected ways that predates the emergence of HIV.

"Just as cancer research facilitated rapid understanding of HIV, HIV has facilitated rapid progress on COVID-19 and finding treatments for COVID-19," Haseltine told Salon. As he explained, Richard Nixon made the fateful decision as president to fund anti-cancer programs that explored the possibility of the disease being caused by a virus. Years of ensuing research eventually helped scientists figure out how to treat victims of HIV, the virus behind the AIDS epidemic. Just as a direct line could be drawn between the anti-cancer programs of the 1970s and the anti-AIDS researchers in the 1980s, so too did many of those scientists move on to fight SARS-CoV-1, colloquially known as "SARS," when that virus hit the world in 2003.

Inevitably, then, many of those same experts were asked to study SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in 2020.

"The result was very rapid progress," Haseltine explained. Notably, Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Joe Biden's chief medical adviser, spent much of his career researching HIV.

If there is a primary lesson in the fact that our war against COVID-19 has been fought with weapons developed in the battle against HIV, it is that we can never predict when, where or how a new disease will emerge — or what previous research might be used to fight it. The work against these menaces never stops, even when we aren't paying attention to them — and that is how, in the cases of the viruses HIV and SARS-CoV-2, the war against one provided weapons for the fight against the other.

"By working so hard against a nearly impossible vaccine to make, we developed incredible tools and insight that made a rapid COVID-19 vaccine possible," Farzan told Salon by email. Reflecting on how the HIV and SARS-CoV-2 viruses "couldn't be more different in their vulnerability to a vaccine," he added that while SARS-CoV-2's emphasis on efficient transmission makes it vulnerable to our immune responses, "HIV-1 is specialized in hunkering down in the face of a vigorous immune attack, and 'knows' our immune systems better than we do."

With more funding and research, it is entirely possible that one day that will no longer be true of HIV, just as it is becoming increasingly untrue of SARS-CoV-2.

Shares