2021 has, in its own strange way, brought autism issues front and center.

First there was the ongoing debate about COVID-19 vaccines, which partially drew on the vaccine skepticism that has existed for years because of the myth that certain inoculations cause autism. Then there was the February release of “Music,” a film by international pop star Sia that aroused outrage from many autistic commentators for its stereotypical and offensive depictions. In March, Alek Minassian, a terrorist who killed 10 people with a van in Toronto, tried to use autism as an excuse for his actions. (The excuse failed, and he was later found guilty of murder.)

These developments speaks to the larger predicament facing autistic people today. Certainly, autistic individuals are making their voices heard, especially online where we have a platform to call out insensitive media depictions. While it is unlikely that Minassian would have ever succeeded in his attempt to use anti-autism prejudices to his advantage, the fact that the court emphatically rejected it at face value reveals that old stigmas are losing their potency.

Meanwhile, as we can see in the vaccine debate, pernicious assumptions about autism still influence our culture — even in ways that on the surface don’t seem to have anything to do with autism issues.

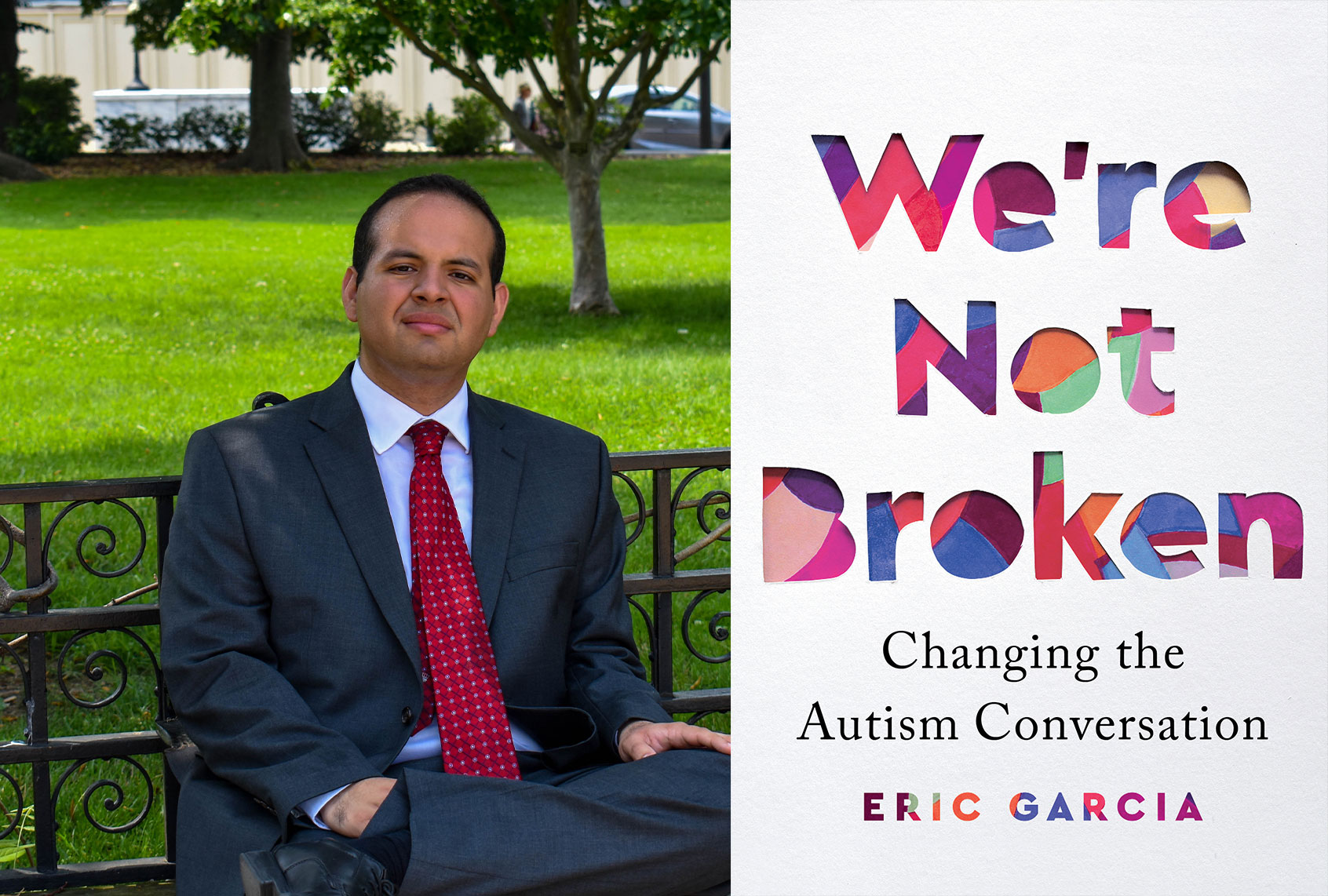

That, perhaps, is where “We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation” enters the picture. Written by an autistic political journalist named Eric Garcia, the book systematically debunks many myths about autism while urging for a national conversation that includes autistic voices. Autistic people are not prone to violence, only able to work in technology or exclusively white and male. Many autistic people are perfectly capable of advocating for themselves, holding down jobs and sustaining meaningful relationships. Being autistic does not turn you into an automaton, and it certainly does not strip you of agency. Indeed, as I can attest from my own experience, it is often more akin to a language difference, or an unorthodox way of understanding the “rules” of human interactions.

Salon spoke with Garcia to discuss his views on everything from autism and neurotypicality (that is, not being autistic) to whether Sia and Donald Trump hate autistic people.

As we’re both on the autism spectrum, I think I’ll be approaching this interview perhaps from a different vantage point than some other people. I’m really intrigued by the fact that you’re focusing so much on changing the conversation about autism from one of “curing” the condition to one of being accepting of neurodiversity. Can you explain how you decided to write a book with that angle in mind?

It began really, really weirdly. I think it was mostly [when] I was writing at National Journal. At the time I had pitched to my editor writing a piece about lots of people in Washington who were on the autism spectrum. I thought it would just be kind of a fun, chatty piece about Washington D.C. life. And then my editor said, “Why should this exist?” And I said, ‘I think we focus too much on trying to cure autistic people and not enough on trying to help autistic people live fulfilling lives. And then he was like, “Okay, that’s this piece.”

So I wrote that piece and then that came out and then I think that the following question was ‘Well, what would that look like?’ And I think the reason why I wanted to write that was (a) I think then it was also me justifying writing that piece, but (B) I thought at the time that we felt that any conversation about autism was almost always questions about curing or questions about vaccines. I feel like they’re rooted in the same idea that autism is something to be avoided, but even if autism can be “cured,” I don’t think that it would even fix the lives of autistic people today.

Not only would it not fix the lives of autistic people today, it would fundamentally misrepresent what autism is.

Yeah, because autism is not a disease. It’s a disability. With that in mind, it’s just like deafness or cerebral palsy or anything else. Even with something like polio, where we basically eradicated polio, it was also a lot of people with polio who were the activists who passed the ADA — the Americans with Disabilities Act. I don’t even think curing autistic people would improve their lives or fundamentally alter who they are. Of course we want to help autistic people with any impairments they have, or any comorbid conditions, or anything like that, but we also don’t want to change who they are. We don’t want to change their fundamental essence. We want to fix the impairments, all the difficulties, but we also don’t want to change who people are. We don’t want to, and you can’t separate the autism from the person.

Let’s take a step back and pretend that society was not organized around the principles of neurotypicality. As a hypothetical premise, what approach should we have to everyone in a way that would welcome both neurodivergent and neurotypical voices? Does that make sense?

That’s a really good question. I think it’s really hard to start from that baseline as such, because basically you have to start everything from scratch. I think if we were to start from that assumption, the thing we would need to do fundamentally is start by asking people, what do they need? And I think for a long time, we’ve talked a lot about autism while talking past autistic people. Does that make sense?

I understand that on a very personal and visceral level.

Before we ever do anything, what we need to do is ask. And we should ask as broad a gamut of autistic people as possible, because your autism is different from my autism, and our autism is different from the proverbial girl in Austin, Texas who is 13 years old. We need to talk with who does have an intellectual disability, and it’s going to be different from somebody who doesn’t have an intellectual disability but might have trouble speaking. All of our autism is going to be very different and we need to include as many people as possible. Now I want to add something. And if you don’t want my asking, because I feel this is very important, but do you mind if I include something?

Of course, just ask.

So a lot of people will say that it is inappropriate for us as autistic people to think that we can speak for autistic people who can’t speak. And they’re correct. We can’t speak for them. But what we can say is that we are more like them than you realize. So a lot of parents will say, “you don’t know what it is like to have a kid who’s constantly having meltdowns.” And you’re right. But even if I can speak, I know what it’s like to have a meltdown. Even if I can hold a job, I know what it is like to have all of your senses on fire. Even if I can go to school, I know what it’s like to misunderstand social work or have trouble doing certain things. I think that it is important to recognize that, yes, we understand what some of those things are like. And that is why we want the same thing for your kid that we want for ourselves.

My next question is about the general thesis of your book. If there was one way that your book could change the national conversation about autism, what would you want that to be?

Just assuming that autistic people should be at the table about anything that pertains to them. I think that that’s the simplest thing.

Now I want to go into the subject of pop cultural representations of autism. As you know, earlier this year I reviewed a controversial movie about an autistic character, [the Sia-directed film] “Music.”

Your review was really good, by the way.

Thank you. I appreciate that. It was scathing because I detested the film. Having said that, I almost feel like it’s worth watching just to understand how autism is misunderstood, because what’s strange about the movie is, I don’t feel like it came from a hateful place. I feel like it came from a condescending place.

Yeah, I think that’s the most important thing to take into account, is that when you do these kind of endeavors, these kind of pop culture endeavors, but you don’t have the input of autistic people, you wind up offending them. You wind up not listening to what they’re saying. I think that that’s why the pushback was so bad. Because I think that could happen isn’t that Sia made a bad movie, it’s that she didn’t back down. She doubled down.

This ties into your book, I think — the idea that condescension is directly connected to the fact that autistic people don’t have a place in the conversation. Someone makes a movie that’s supposed to be for a certain community, but it doesn’t ever occur that excluding people from that community inherently defeats the purpose. And this would be true, regardless of which community one is trying to speak for.

I think that it’s because a lot of people assume that autistic people can’t speak for themselves or that autistic people can’t describe their own experiences. They’re not experts on their own experiences.

How the conversation has evolved about vaccines since the pandemic? How do you feel that that evolution has in any way changed the aspect of anti-vaccine debates that specifically pertains to the infamous autism myth popularized by Dr. Andrew Wakefield?

The autism vaccine myth and panic is to the COVID vaccine disaster what “The Hobbit” is to “The Lord of the Rings,” so to speak. It laid the groundwork for this current crisis. You would not have as many people skeptical of vaccines, or you would not have a climate that accepted this, or you would not have this kind of conspiratorial mindset about vaccines without the autism vaccine panic and myth.

Now I have to ask about the possible connections between prejudice against autistic individuals and the Trump movement in general, because I can tell you from personal experience, I’ve had Trumpers insult me by citing my autism. Do you think it’s just them playing to their most vulgar instincts or is there a trend here?

I think that it goes back to Donald Trump saying that autism has become an epidemic during a Republican primary debate. To your point, it goes to their kind of base, these bullies. A lot of these people are bullies and they’re going to find something, but there’s also this kind of weird, at least from my experience, there’s this weird kind of psychosocial anxiety about autism because some white nationalists think that it’s something that — I’ve seen it on Twitter — think that like only like the psychologically superior or autistic, like kind of like the next generation of Übermensch or whatever. I’ve also seen them say autistic people are lesser or they’re inferior. Nobody has ever argued white supremacists make any sense, but they’re very contradictory here.

Is there anything else that you feel is important that needs to be added?

A lot of people misunderstand what I say, what I want, which is for you to accept autistic people. A lot of people think that I say that that means that autism is all rainbows and butterflies. Just like with any disability, there are challenges. And just like with disabilities, any disability, there are impairments. But what I’m arguing fundamentally is that that being disabled does not warrant you losing your rights, your humanity or your dignity. And if there is anything that I’m arguing in this book, it’s that autistic people are humans and they are fully deserving of being treated as human beings.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.