Earlier this month, I compared Joe Biden to John F. Kennedy, who salvaged his image after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 by admitting his mistake — and learning from it. I acknowledged that the parallel was imperfect, since “foreign policy and domestic policy mistakes are obviously very different kettles of fish.”

How quickly things change. Thanks to the rapid collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban takeover, those two kettles of fish suddenly look awfully similar. As with Kennedy, it is likely that Biden’s presidency can avoid being defined by this fiasco. Providing, of course, that Biden and his supporters learn the right lessons from history.

There are three big ones.

First of all, the main political similarity between the Bay of Pigs and the Afghan withdrawal is that, on each occasion, a Democratic president paid the price because Americans take our imperial ambitions for granted. In Kennedy’s case, military hawks had convinced him that Fidel Castro’s Communist regime could not be tolerated because Cuba was too close to American shores — and that it could be overthrown without a risky invasion by U.S. troops.

For Biden, as Salon’s Amanda Marcotte points out, it was the notion that the U.S. could somehow have “saved” Afghanistan by staying there just a little bit longer, despite 20 years of futile conflict. On both occasions, painful realities intruded on these jingoistic delusions. Castro still had deep public support among the Cuban people in 1961, and the Taliban had never been fully defeated in Afghanistan. If anything, the Taliban had improved greatly as a tactical and strategic force after 20 years of engagement with the U.S. military. When Biden told the American people that he was “the fourth president to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan — two Republicans, two Democrats,” he was making an obvious and valid policy point. There was no end in sight except through withdrawal.

So that’s the first lesson: Before you view a foreign policy fiasco as a failure, ask yourself how it looks in the broader context of history.

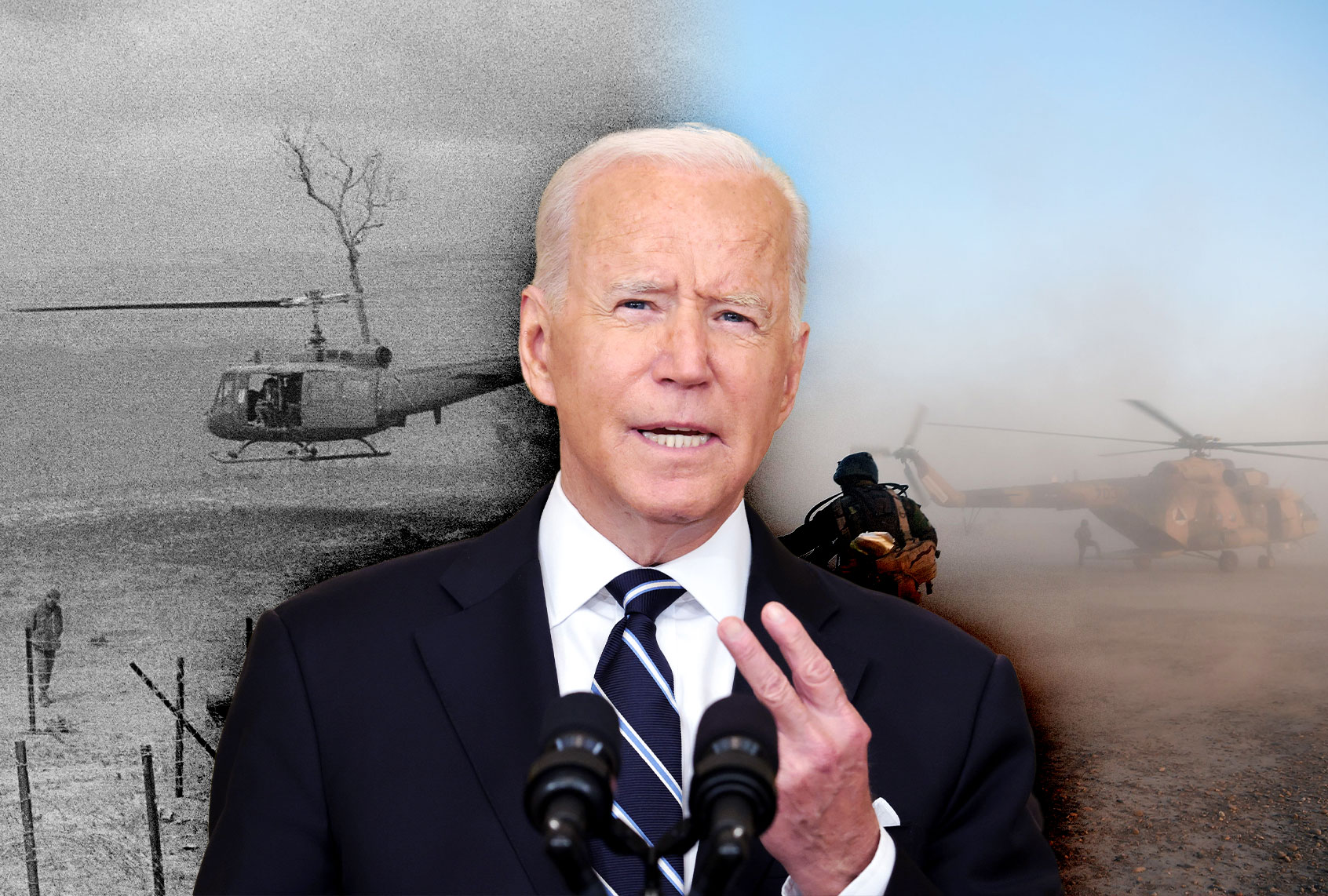

Even so, it looks from here as if the Biden administration failed in both strategic and communication terms, repeating its chief error on the eviction moratorium issue by being caught unprepared. Until the last minute, there was no clear plan to get U.S. and Western civilians and Afghan refugees out of the country. (Arguably, there is no clear plan now.) That ineptitude no doubt cost innocent lives and, even setting aside moral issues, reinforces the same message sent when the U.S. abandoned its Kurdish allies in Syria: We are not a reliable friend. Biden foolishly vowed in July that there was “no circumstance where you see people being lifted off” — referring to America’s infamously bleak withdrawal from Vietnam — after a rapid Taliban conquest. This, of course, was exactly what happened. It’s as if the president had tempted fate to humiliate him.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Indeed, Biden’s unfortunate historical analogy deserves more attention, since it illustrates the second major lesson that the president and his supporters could glean from the dramatic events of the past week: Optics aren’t everything, but they matter.

Gerald Ford was president when the U.S.-supported government of South Vietnam fell to the Communists in 1975, but politically Saigon’s collapse did not hurt him. U.S. military forces had ended their involvement in the war two years earlier, to the great relief of most Americans. No doubt the harrowing images of helicopters taking off from the U.S. embassy roof, and depicting the desperate plight of Vietnamese refugees, were traumatic for many American observers, and some blamed the Ford administration. (Ford had been in office for just eight months, only slightly longer than Biden has now.) As Biden just did, Ford reminded the American people that this war had to end one way or another. He was also able to improve his reputation with some meaningful foreign policy accomplishments, including the rescue of American hostages held by the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia.

Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican president with a sterling military record, faced his own embarrassing foreign policy crisis in 1960, his last full year in office. It began when a CIA spy plane was shot down deep inside Soviet territory that May, weeks before an important peace summit. Eisenhower initially denied that the U.S. government was involved, but the Soviets collected incontrovertible evidence that wasn’t true. Faced with sharp criticism for not being in control of his own administration, and for making America look bad, Ike finally owned up to his role in authorizing and overseeing the controversial spy missions, defending them as necessary for national security. He was praised for his frankness — but pretty much blew up the peace talks. That of course was a dramatically different era, and Eisenhower was a universally respected figure, even by political opponents. When a congressional ally defended him before the House of Representatives, members from both sides responded with a standing ovation.

Joe Biden has no such reservoir of goodwill, and also has no foreign policy good news to offset the catastrophe in Afghanistan. The good news, perhaps, is that he can change both those things. Despite Donald Trump’s lies about the 2020 election, Biden is not a polarizing figure and is not widely despised (as Trump was and is), even by his enemies. While the optics of this past week have been dreadful, Biden is not ultimately to blame for what happened in Afghanistan, and most Americans across the political spectrum were eager for the U.S. to withdraw.

There’s another possible lesson of history, one Biden may not wish to contemplate too deeply: Sometimes foreign policy goes so wrong it costs presidents their jobs — and even the support of their own party.

After the Tet Offensive in early 1968 — a string of victories by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese military that made clear the U.S. and South Vietnam were not winning the war — President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not run for re-election. (Johnson had narrowly won the New Hampshire primary over antiwar candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy, but clearly faced a stiff battle for the Democratic nomination.) Despite Johnson’s withdrawal, nothing went right for Democrats after that. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who would have likely been the strongest nominee, was assassinated in June, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey wound up winning the nomination — without even running in the primaries — at the disastrous Chicago convention, featuring pitched battles between police and left-wing demonstrators. Richard Nixon was elected in the fall, at least partly because segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace (a once and future Democrat) won several Southern states as a third-party candidate.

Twelve years after that, President Jimmy Carter did run for re-election even after the disastrous failure of an effort to rescue American hostages in Iran, but his perceived weakness likely doomed his campaign from the beginning. Carter held off a primary challenge from Sen. Ted Kennedy (the only time he ever ran for president) but was wiped out by Ronald Reagan in a milestone election. Intriguing but unanswerable questions hang over both those elections: If Bobby Kennedy had lived, and if Teddy Kennedy had prevailed against Carter (or if Carter had quit the race), would Democrats have held onto the White House? Recent American history might look very different in that alternate universe.

In this universe, however, Joe Biden is president, and Afghanistan has fallen to the Taliban. It is difficult to imagine any scenario where things turned out differently in Afghanistan if Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Ted Cruz or Bernie Sanders were president instead. So the smart money says that Biden won’t be much affected by this in the long term, any more than Ford was by the fall of Vietnam or Kennedy was by the Bay of Pigs. If, that is, our current president is willing to learn the lessons of history.