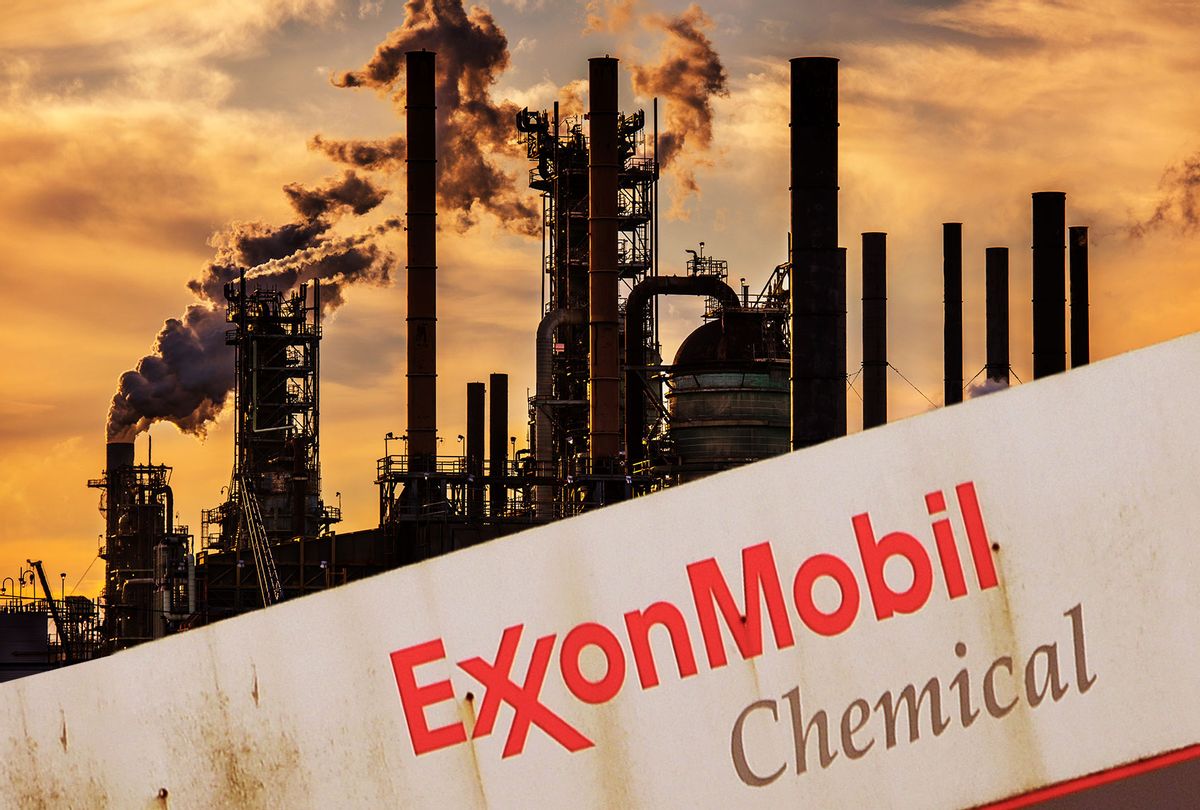

For more than a century, the oil giant ExxonMobil (and its predecessor companies) has operated the three highest-polluting oil refineries in the nation. Around these refineries in Baytown and Beaumont, Texas, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, residents have been plagued with Exxon's toxic emissions for decades, which have included foul-smelling neurotoxins, cancer-causing soot and fiery explosions that have sometimes injured or even killed workers. In recent years, environmental groups have filed an array of lawsuits against Exxon, claiming the company has inflicted extensive harm on these communities. Exxon has aggressively fought back on the legal front, downplaying residents' concerns or flat-out denying their allegations.

But in reality, Exxon's footprint in these cities is complicated. Throughout the years, the company has established itself as a mainstay in these communities, buoying their economies with job opportunities and investments in local organizations. Exxon has donated significant sums to local charities, school boards, museums, parks and colleges. As the company phrases it in PR material, it seeks to focus "on community and business needs such as health care, education and economic development" and to address "strategic local priorities where we do business around the world."

But as Exxon and other major fossil-fuel companies face increasingly acute waves of bad publicity around the world, to accompany their apparent dearth of legal accountability, environmental advocates are calling out these donations as empty gestures or "window dressing," an effort to buy local goodwill on the cheap without addressing the harmful consequences of Exxon's business.

According to a Salon analysis of Exxon's 2018, 2019 and 2020 "giving reports," the company – through its affiliated foundation and various subsidiaries – has flooded institutions and organizations based in Baytown, Beaumont and Baton Rouge with millions of dollars in charitable donations.

In Baytown, a southeast Texas city of about 76,000, where Exxon operates the second largest oil refinery in the U.S. (2,400 acres) and ranks as the city's largest employer, the company gave at least $770,500 to groups and institutions in the area during 2018. In 2019, it upped the ante, donating at least $792,000, with notably large contributions to the City of Baytown, the Goose Creek Consolidated Independent School District, and Baytown's Habitat for Humanity and United Way chapters. Exxon also donated hundreds of thousands to Lee College, a Baytown community college that hosts the company's Energy Venture Camp, Signature Technician Training Program and Community College Petrochemical Initiative — all of which are designed serve as career pipeline training initiatives designed to mold future oil-company employees.

During that same three-year period, Exxon became mired in controversy in Baytown and the surrounding area. In April of 2017, the company lost a $20 million lawsuit over a five-year violation of the Clean Air Act. The suit, alleging that Exxon spewed 8 million pounds of hazardous chemicals into the surrounding air, brought about the "largest penalty resulting from a citizen suit in U.S. history," according to environmental group Environment Texas.

In 2018, The Texas Observer reported that Exxon may have misled the state comptroller in seeking $65 million in tax breaks for its Baytown facilities by claiming that its regulatory permit applications had not yet been filed. In reality, Exxon had already filed these permits to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) a year earlier. In securing the city's go-ahead, Exxon had to request approval from the Goose Creek school district — one of the company's major philanthropic beneficiaries in 2018 and 2019.

Bad press kept coming. In July of 2019, part of Exxon's Baytown Olefins plant erupted in flames, injuring 37 people with and prompting two worker-led lawsuits totaling $2 million. The next month, Harris County and the TCEQ filed their own joint lawsuit against Exxon for violating the Texas Clean Air Act and Texas Water Code as a result of the explosion, citing that the company had released numerous air pollutants into the surrounding communities.

To get a better sense of the connection between Exxon's giving and its efforts to fight back against bad press, Salon spoke with a number of environmental advocates in the Gulf Coast who have studied the company's presence in the area.

Adrian Shelley, the director of Public Citizen's Texas office, told Salon that Exxon's contributions are "very plainly a PR calculation."

"The best way for Exxon to invest in a community where it is located is to limit its own emissions," Shelley said in an interview. "That's the way for Exxon to really benefit a community. Anything else is window dressing."

Marylee Orr, executive director of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), echoed Shelley in an email: "For the last two decades or more, I have seen industries make donations to communities, which LEAN is not against. But the real gift that every community wants is less air pollution, less water pollution, cleaner land and a better quality of life."

In 2016, LEAN, sued Exxon, alleging that the company's Baton Rouge refinery had violated the Clean Air Act by emitting "thousands of pounds of harmful and hazardous air pollutants above permitted limits" despite a 2013 administrative settlement with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality preventing it from doing so. A year later, in March of 2017, Exxon was dealt a damaging legal blow when the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled in favor of 8,500-plus Baton Rouge residents who sued the company over an explosion at Exxon's plant in 1993. The explosion, which killed two people and injured thousands in various ways, has been described as having long-term traumatic effects on the city.

Exxon's Baton Rouge facilities may also rank as the company's worst in terms of environmental metrics. According to the Political Economy Research Institute, the firm's operations in Baton Rouge accounted for more than a third of Exxon's entire air releases in 2018, which had a disproportionately negative impact on Black communities. According to a Reuters report, one in every three residents living in these communities said they either had breathing problems or knew someone who did.

As in Baytown, Exxon's has over the years showered Baton Rouge institutions with millions of dollars — which as skeptics observe is a pittance for a corporation that earns tens of billions in profit every year.

Salon found that Exxon's giving in 2018 and 2019 was roughly equivalent, at about at least $1.6 million each year. Chief among its beneficiaries were the community YMCA, New Schools for Baton Rouge, the Mid City Redevelopment Alliance and the Foundation for East Baton Rouge School System, whose school board approved a $21 million tax break for the company in February of this year.

Exxon also donated heavily to Louisiana State University, the major public research institution in the state, where the company also administers a scholarship program. Since 2011, Exxon has given at least $9.8 million to LSU, and actively recruits its graduates.

Neil Carman, clean air director at the Sierra Club Lone Star Chapter, who formerly worked as an environmental official for the state of Texas, told Salon that Exxon's donations to universities like LSU are an attempt to silence criticism from the academic sphere.

"Exxon can buy powerful influence in academia and it makes it hard for professors to speak out against [the company]," Carman told Salon over email. Carman recalled the late Marvin Legator, who was chairman of the Environmental Epidemiology & Toxicology department at a University of Texas medical institution in Galveston, next door to Baytown. Carman said that in 1992 Legator "was threatened with termination if he spoke against Exxon" on benzene emissions. "It was shocking to hear but not surprising."

Exxon has also directed a significant amount of money to Beaumont, another southeast Texas city of about 118,000 where Exxon is the third-largest employer, operating a refinery and two chemical plants. The company donated at least $731,350 to various institutions and organizations 2018, and increased its total investment to at least $860,000 in 2018. Recipients in Beaumont included the Southeast Texas Family Resource Center, the Texas Energy Museum, the Greater Beaumont Chamber of Commerce and the Beaumont Independent School District. In 2016, Beaumont's school district had approved the largest tax abatement for Exxon of any district in the country, according to the Beaumont Enterprise, apparently saving the company nearly $54 million by 2030.

Exxon has also poured money into Lamar University, Beaumont's premier educational institution, with those contributions totaling at least $646,050 since 2018. Like Lee College in Baytown, Lamar benefits from an Exxon-sponsored scholarship program, frequent company recruitment events, and an Exxon-funded student ambassador program targeting high school students.

But even as Exxon pours thousands of dollars into Beaumont, its operations continue to take a negative toll in the city's communities, and specifically its neighborhoods of color.

For decades, residents of Charlton-Pollard, a 95% Black neighborhood in Beaumont, have worked to capture the attention of the EPA to what they say are Exxon's toxic emissions. According to a 2017 investigation by The Intercept, residents have dealt with daily minor ailments like dizziness, headaches, tearing eyes and congestion that they attribute to Exxon's nearby refinery. Far more troubling, they also believe the plant — which often conducts controlled explosions called "flares," spraying hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide throughout the surrounding area — has led to a significantly elevated incidence of cancer, heart disease and respiratory illness.

According to the EPA's data, residents of Charlton-Pollard have a risk of up to 75 in one million of contracting cancer from air pollution, many times higher than the national average of less than one in a million, as the Intercept noted. (It should also be noted that even that statistic depends on Exxon's reported emissions, which it has been known to undercount.)

In 2017, the EPA finally settled a lawsuit originally filed by a local minister, the Rev. Roy Malveaux, in the late 1990s alleging that the company's emissions had violated the Civil Rights Act by disproportionately impacting Charlton-Pollard residents. The decision — which came after years of state and federal indifference — involved "one air monitor about a mile away from the refinery and two public meetings to discuss the data collected by the monitor," reported The Texas Observer.

Beaumont has also seen its share of operational accidents. In 2018, a Jefferson County jury awarded $44 million to the family of an Exxon worker who died due to workplace negligence. The following year, the Department of Justice and the EPA announced a settlement with Exxon, ordering the company to pay damages resulting from a 2013 Beaumont refinery fire that killed two employees and injured 13 others.

Salon reached out to Exxon to ask about the apparent relationship between the company's philanthropy and the controversies it has faced in these communities.

"We voluntarily share our reports which help demonstrate the charitable commitment to communities where we operate," Exxon spokesperson Todd Spitler said in a statement to Salon. "Our report contains a specific level of charitable giving and may not include all local charitable contributions that the company or its affiliates and subsidiaries make, including the ones you have referenced in Baytown, Beaumont and Baton Rouge.

"We routinely assess our community charitable giving program and adjust as needed, based on where there is significant need and where significant impact can be made. This includes our donations for disaster relief to affected areas."

Salon's reporting found one puzzling fact: For unclear reasons, Exxon changed the reporting threshold for its donations from $5,000 in 2019 to $100,000 in 2020, resulting in greatly reduced transparency for that year. Asked about this change, Spitler said that Exxon makes "multiple charitable contributions at varying and adjusted amounts year to year. We set a threshold/cutoff amount for what is voluntarily reported on our website." He declined to comment on why the new threshold was applied in 2020.

According to Exxon's 2019 Giving Report, the company has recently donated to groups that at various times have been accused of promoting "climate denial," including the Manhattan Institute ($90,000), the Washington Legal Foundation ($40,000), the Hoover Institution ($15,000), the Federalist Society ($10,000), the Center for American and International Law ($5,000) and the Mountain States Legal Foundation ($5,000). If those donations continued (or even increased) in 2020, they would have fallen under Exxon's new reporting threshold, meaning they would be invisible to outsiders.

Tim Donaghy, a senior research specialist at with Greenpeace USA, expressed concern about the consequences of Exxon's change in its reporting threshold.

"ExxonMobil's past funding of millions of dollars to climate denial groups helped spin a web of misinformation that still stymies progress and delays necessary action on climate today," Donaghy said by email. "If ExxonMobil is providing less public information about its donations, that backtracking on transparency could have negative consequences for people all around the globe who are already feeling the deadly impacts of oil and gas-related pollution and climate impacts."

Shares