Despite having never been in a band or actually showing any real aptitude for playing the drums, I've always in some small way identified as a drummer. I got my first drum set when I was 16, with heavy metal dreams and a touch of teenage angst. Thirty years on, I have a digital kit, and I take lessons periodically. I may not be able to play (well), but I still love the drums.

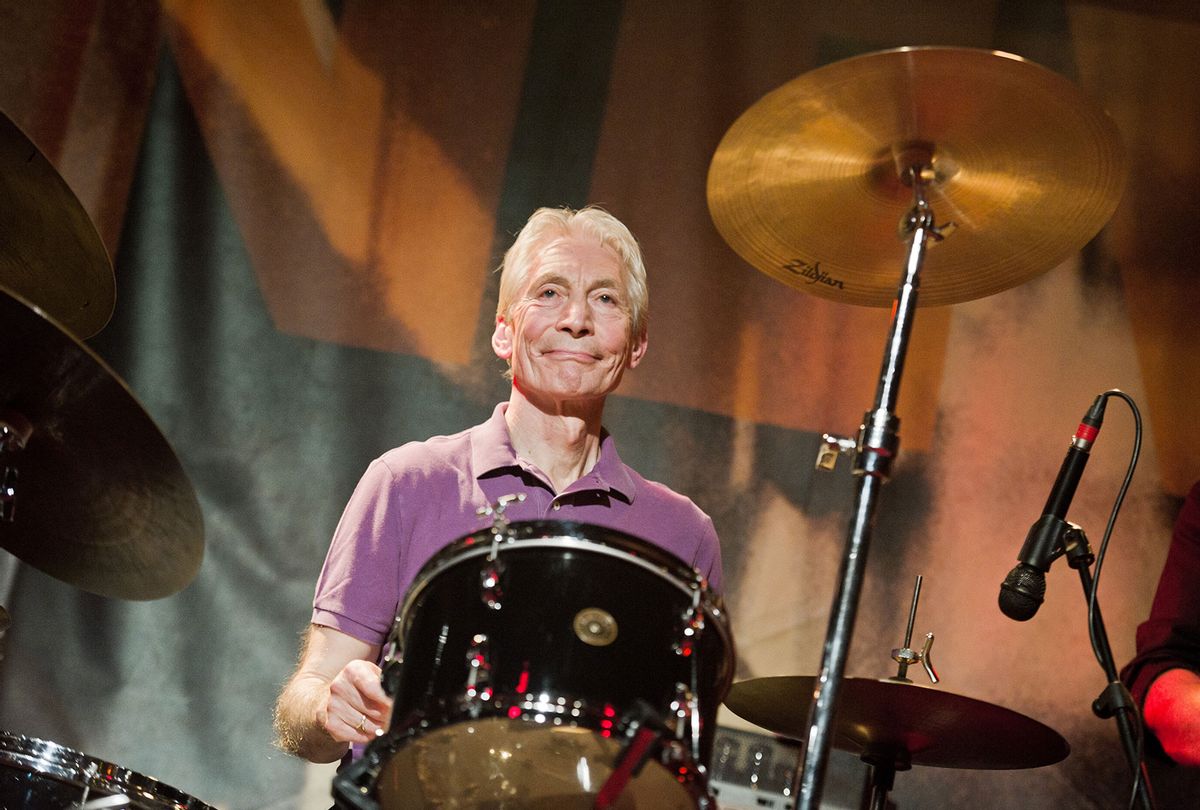

So I was saddened by the passing of Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts. Watts played with the world's biggest rock band for a staggering 58 years and was happily married for 57 until his death at 80; beyond his musical talent, Watts was remarkable for being impervious to the rock-n-roll debauchery that defined his bandmates. He met celebrity with indifference. "Playing the drums," he said, "was all I was interested in. The rest made me cringe."

As well as his jazz-inspired, swing-infused drumming style, Watts was known for his steady, Zen-like eccentricities. On the road, he would draw a sketch of the bed of every hotel room he slept in. In the midst of post-show bedlam, he would calmly return to the stage to meticulously check that his drumsticks were placed just so on his kit, even though it would soon be dismantled and stored on a tour bus. Over the years he said that he could easily accept the Stones coming to an end, but that without drumming, he would probably go mad.

Though that might sound extreme, there's some scientific basis for his claim. Research has linked musical engagement — and drumming in particular — to well-being and human flourishing, which is linked to physical health and life longevity. In ancient philosophy, the highest human good is to attain Eudaimonia, to live in harmony with the highest version of yourself. Watts certainly came close to attaining this, and it is arguably in part because, before he was anything else, Charlie Watts was a drummer.

Multiple studies show mental perceptions have direct impact on our physical health. For example, subjective age — the age you feel versus the age you are — has been shown to be an important predictor or late-life health outcomes, including level of risk for stress-related illness, depression, and the negative physical effects of a sedentary lifestyle. An equal factor is subjective wellbeing — how much you feel your life is going well.

Ruth A. Dubrot, a lecturer in music education at Boston University, sought to identify ways in which engagement with music impacts the lives of older adult blues/rock musicians who regularly participate in a blues jam. She found that "eudaimonic well-being is the result of active engagement in human activities that are goal-directed and purposeful," and that having a positive subjective wellbeing involves "the self-realization of individual dispositions and talents over a lifetime."

A 2003 study published in the American Journal of Public Health investigated drumming as a complementary therapy to treat addiction. The study's author, anthropologist Michael Winkelman of Arizona State, concluded that drumming "produces pleasurable experiences, enhanced awareness of preconscious dynamics, release of emotional trauma, and reintegration of self." Winkelman noted further that drumming "alleviates self-centeredness, isolation, and alienation, creating a sense of connectedness with self and others" and "provides a secular approach to accessing a higher power and applying spiritual perspectives."

Another study, published in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Well-being in 2018, investigated the relationship between group drumming and wellbeing; the study's co-authors found that, through drumming, certain emotional, psychological, and social dimensions of wellbeing emerged, including agency, accomplishment, engagement, identity, hedonia (positive affect and pleasant physical effects of drumming), and social well-being.

But if joining a drum circle — gathering in a ring to drum, purely to form a group consciousness — sounds a bit too woo-woo, there are health benefits to jamming out by yourself, too. Researchers at multiple UK universities found that rock drumming for one hour per week improves how children with additional educational needs; their study specifically focused on children with autism, and suggested that drumming for an hour a week helped them perform better in school, particularly by helping them improve their dexterity, rhythm, and timing.

Beyond mental health effects, drumming provides a physical workout. The so-called Clem Burke Drumming Project, a drumming-related research collaboration involved in the aforementioned childhood drum study, also found drumming requires enormous stamina, burning between 400-600 calories an hour. In tests conducted for the project, drumming brought Burke's heart rate up to between 140-150 beats a minute on average, with a peak of 190, which is comparable to that of top athletes — with the difference being that a drummer on tour will perform to this level nightly, far more frequently than most participants in professional sport.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

And more good news: While percussionists are stereotyped as unintelligent, data suggests otherwise. Swedish researchers found drummers score higher on intelligence tests, and say that the "rhythmic accuracy in brain activity that is observed when a person maintains a steady beat is also important to the problem-solving capacities measured with the intelligence tests." Another study investigating a drummer's ability to perform complex motor tasks with their two limbs independently found that drummer brains are wired differently, having a "more efficient neuronal design of cortical motor areas."

Of course, we can only speculate on the impact drumming had on the actual physical and mental health of Charlie Watts. But research certainly supports that drumming and musical engagement in particular can only be strong factors to a person's general wellbeing, and directly contribute to positive health outcomes and longevity.

As for my own drumming, every now and then on the rare occasion I actually sit down to play, I have a fleeting moment of not overthinking or being self-conscious where I experience pure flow. It's that feeling, I realize, that keeps my appreciation for the drums alive — not with the ambition of rock stardom, but the aspiration to arrive at some Eudaimonia of my own, and to feel that little bit more like Charlie Watts.

Shares