What do you think of when you see the word “cult”? A bunch of Manson girls wending their way toward Cielo drive? A Peoples Temple flock forced into suicide in Jonestown? What you probably don’t think of is a bunch of kids from a prestigious liberal arts college being manipulated by the dad of a fellow student.

When writers Ezra Marcus and James D. Walsh published “The Stolen Kids of Sarah Lawrence” in New York magazine in 2019, an immediate flurry of attention followed. The story — of a charismatic, just-released-from-prison parent who reportedly manipulated, blackmailed, abused and ultimately divided a group of friends — seemed like a tabloid-ready tale. But it was not sensational. It was instead an object lesson in the life cycle of an harmful relationship, and how vulnerable anyone can become.The story led to a development deal from Amazon, and an indictment for sex trafficking and extortion for the man at the center of it, Larry Ray.

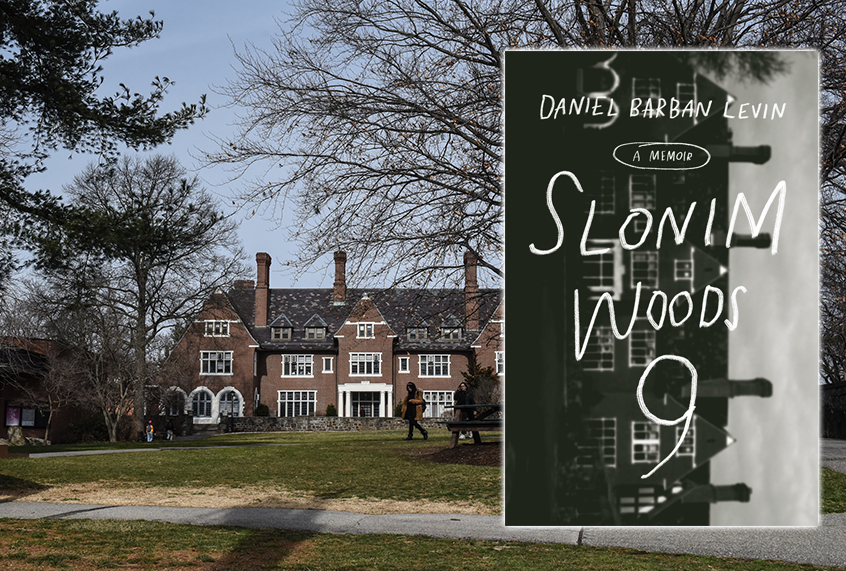

And now, one of the former members of the group, Daniel Barban Levin, has written his account of what went on during those tumultuous, painful years of his young adulthood. It’s an intense tale of coercion, humiliation, gaslighting and physical torment. It’s also one of hard-won survival, and creating a life after the unimaginable. Salon spoke to Barban Levin recently via Zoom about writing his way to a new narrative, when he knew he had to walk away, why nobody sets out to join a cult — and what really happened at Slonim Woods 9, the name of a dormitory on Sarah Lawrence’s campus from which Barban Levin took his memoir title.

As always, our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

It takes a lot of courage to make yourself vulnerable again, to relive that experience writing about it.

The process of writing the book did a few things for me. I had gone through an experience that seems explicitly designed around telling a new story for me about who I was and what my memories even were.

The man who abused me was such a talented storyteller that he could convince you that something that wasn’t real was real. Writing was not only about telling my story as I remember it and believe it. I spent a year writing this, and every day of writing it I had to make the claim that my account matters and is valid. I’m staking my flag in my own credibility, and I’m saying I trust myself. Then also even further, it’s kind of an attempt to trust other people, just to give people my story and hope that they will believe me.

You talk about this man who was such a skillful manipulator and storyteller and disruptor of reality. When you think about him now, how would you answer the question “who is Larry Ray?”

That’s a really hard question to answer. I will say that for a lot of the time that I was in his presence, that I was actively being tortured even, in those moments, I was asking myself that question. There were a lot of answers, and it was unclear to me where those answers were coming from and what was real and what wasn’t. He was a father, he was supposedly a Marine, he was supposedly an intelligence officer. He had shown me photos of himself with George H. W. Bush and Gorbachev and they looked like pals, so there were all those things.

The process of trying to answer that question, to arrive at a clear definitive answer to who is this man, or even what are his intentions, was for me kind of a trap. If you spend your energy trying to figure out who your abuser is or if they’re a good person, you’re not leaving. The thing on the other side of the scale that outweighs everything is, he was the person who was hurting me and I didn’t deserve that.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

What this book illuminates so clearly to people who have not been in what we would characterize as cults, or in abusive relationships, is they don’t start out abusive. You don’t get into them because you think, “I would like to be tormented and abused.” How did it start for you, where you became drawn in with this person?

Nobody joins a cult. They join a group of friends or they join a self-help group or whatever it is. But nobody says, “Oh, this is a cult and I can’t wait to get involved.”

In my experience, this is my friend’s dad who just showed up at our dorm. We were on the meal plan, eating the not very good college food, and he showed up and was buying us fancy takeout. He said, “Come have some pasta,” and that’s hard to say no to and is innocuous. Then between there and me being in his apartment in Manhattan living there with all my friends and him torturing me is many, many steps. It’s a slow burn, bringing out the frog in boiling water kind of thing. I tried to lay out in the book all of those steps, and how you get from A to Z . You don’t encounter someone who’s obviously an abuser and then stick around.

One of the first things that happens is building intimacy and building trust.

In some ways I think I was vulnerable to that kind of insidious intimacy because of my age. When you’re 18, 19, 20, you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing, which is questioning. You’re looking back on where you grew up, how you grew up, what it means to be a person or be an adult, to make an impact in the world. You’re questioning those roots and you’re trying to grow your own branches. That’s a really tender and potentially really productive place to be. But in this very specific instance, if someone wants to, they can slip in and leverage that vulnerability.

It’s very common in abusive relationships in cults like this, or in any kind of a cultic relationship, for someone to do what’s called love bombing, where they show up and then they make you feel fantastic, they make you feel relieved. All of your things that you were worried about, your questions — in my case about my masculinity, about my body, about my sexuality, about how to be a good person. This person was saying, “You don’t have to ask those questions anymore or feel that you’re shouting them into a void, because I will answer them.” I also happened to grow up in a place where therapy wasn’t really a thing that we would do, so I didn’t feel that I had some nonjudgmental third party to go to, to ask these questions. He made himself that person.

That’s how you get to this escalation of slowly changing your reality.

One of the things I came away with was an understanding of how tenuous our attachment to our reality is. We currently live in a world, in a country, where people believe very different versions of reality than we might believe. It feels it’s conceivable that someone could think that clear historical events occurred completely differently than we think they did. This was an experience with a man who was able to make me question what had actually happened an hour ago, a year ago, ten years ago. Part of that was just that slow burn of manipulation and the pressure, the abuse. There was also peer pressure, and me seeing my social group believe these things made me want to believe them.

It reminds me of the dynamics in abusive families, where there is no one to check your reality against. You were going along with things and that part of your brain that was saying, “This is weird,” wasn’t speaking out.

It makes me wish that everyone had a version of that checklist that I just happened upon later on and to hold it up against not just if you’re in an abusive group, but even in the abusive relationship or what you suspect might be. I had been able to say to myself, “Well, the fact that it feels impossible to question or dissent or talk about what’s happening here, and that in itself is a real problem.”

What I was thinking in my head was, “Okay, my friends are going along with this, they even seem to be supporting it as they’re actively sitting around watching me be abused. Maybe it’s supposed to be something that’s good. At the same time, I also know that I’ve been in that position and I’m pretending I feel okay with what’s happening. So are they doing that?” But it was impossible for us to check in because there was this constant fear that the other person wouldn’t. The consequences were too high if they didn’t agree with you and they would go straight to your abuser and say, “This person has turned against you.”

You had situations where people, including you, were singled out, humiliated, attacked, confronted. I want to ask you about that, because there are so many choices that you had to make as a narrator. You, taking control of the story as an author, had to decide, “How do I tell this story?”

I decided early on in the process of writing this that shame is a tool that men like this use to keep people that they’ve hurt quiet. If I embraced who I was, who I am — which is someone who experienced this abuse, who survived and who is here now to stand by my account — if I took that shame and turned it inside out and made it my power, then I could live. But continuing to hide and to let the shame that was really him, that was his voice, dictate how I live my life and what story I told about myself, then I would never really get to fully live my own life.

It’s about owning the story rather than rewriting it or reinterpreting it.

It’s an act of trying to believe that if I tell people what happened to me, they won’t look at me with disgust or hold me at arm’s length. The people who love me now will still love me after they read the book. I am not alone, and in fact, after telling my story, maybe will be even less alone.

It has now been two years since this story first published. It had an immediate impact when it was published. It became a criminal investigation, a case that is still going on. What was the reaction directly to you after this came out?

When I was first contacted by the New York Magazine reporters, I had been hiding for many years, truly in fear that someone from this group would show up and try and bring me back or something. That fear, I managed to bottle up over time. At first, I was afraid every time I walked around the corner, and that got less severe.

I got contacted by these reporters, and I had told myself that surely the group — maybe it had fallen apart or it had changed. I was still afraid that Larry was around. They told me not only did it still exist, but that the story they were reporting at first was that my friend had apparently poisoned some people in our college. I think most people, if they got that call, would be shocked and wouldn’t know how to react. But I knew exactly what they were talking about and that it wasn’t true because I’d heard the exact accusation told many, many times when it was within that group.

It became my responsibility suddenly to protect my friends from the abuse leaking out beyond the confines of the room where it had always happened into the world and affecting her life. So I told the story to them and was candid about it. It felt like suddenly I was exposing myself. I was speaking out against the man who I had believed for a long time if I even said something negative about him in private, he would somehow know and show up and hurt me. It felt to me like if people don’t believe me, then I’ve just fully put my head on the chopping block, but okay, I’ve protected my friend. If they do believe me, then in fact, I may be a little bit more safe.

When the indictment happened, it did feel at least partially an immense relief that something had come from this, that I had been believed not just by people but by maybe the justice system. It made me feel a little safer.

The narrative so often in stories of crime or abuse or cults is to look at the leader, to look at the perpetrator. You don’t do that. You don’t try to explain him or understand him or delve into the why of him. I’m sure that that was a choice.

I found for a long time that I could not engage with the type of content that I’ve seen out there, in which people depict cults and true crime things and thrillers that try to deal with this. My experience has been that our obsession with cult leaders, with the horrible, monstrous outliers of humanity, and our obsession with the abuse that the victims have suffered over the victims themselves, made it impossible for me in the process of coming out of this to see myself inside the word “cult.” There are all these cultural connotations around what a cult is that that makes it very other. When we imagine a cult victim, we don’t imagine a person really, or certainly not a person we know. I was so afraid to admit what had happened to me because it felt like I would become a freak, for lack of a better word.

I wanted to, as best as I could, normalize the experience and to expose how one gets pulled into this, how it’s a result of not particularly unfamiliar social dynamics. I didn’t want to put the abuser up on a pedestal and then say, “Oh, look at this,” because people seem to do that with these people, like, “Look at how incredible and strange they are, In fact, he’s just a sick human being who’s very ill, you know?

It’s been nine years. What is your life like now?

I was always a writer, and so the time in between, I was still writing. I lived in New York for a while. I got offered a job in New Hampshire taking care of Robert Frost’s house and I did that for a while. Then I got into grad school and jumped at the opportunity to move as far away from the East Coast as possible. It has given me a breathing room to just have space. I went to grad school for writing out here in Southern California, and now I live in L.A. I’m very lucky to have a great group of friends out here and to have a pretty full life. A lot of the past couple of years has been living inside of the retelling of this story, which is its own kind of re-traumatization to weather and survive.

Are you following the case and the key people involved in it, or have you distanced yourself from that narrative?

It’s hard to get away from, because there are all kinds of people in my life — well-meaning people — who will let me know when something’s happening. I feel aware of the major things that have gone on. I’m certainly conscious of every time the trial is pushed back. A lot of space in my brain is taken up with just anticipating that trial and what it means.

This is not obviously a self-help guide, this is not a how-to. But I’m sure when you talk to people, they ask you, “What are some of the red flags that I should maybe pay attention to?”

There is a set of things if we’re really just looking for red flags. We’re talking about really familiar dynamics, but just taken to their most toxic extremes. What a cult is, it’s many different things. It can be a group that’s focused on a leader who’s alive and that leader isn’t accountable to a higher authority, but that can be what a political party is also, in its worst form. It could be just a group that’s focused on bringing in new members, which sounds like a club, but if you push that too far, it’s a cult. It could be a group that discourages dissent, but that could be the worst form of a government. Or it could claim an exalted status for itself and its leadership, which sounds like a religion, but again, taken to the extreme.

All of these things, they exist in other facets of our social lives, but it’s just when they’re turned so far that they wipe out every other aspect of just being a regular human being that they become this toxic thing.

It brings me to the question of, how did I answer that question for myself at the time? How did I feel that what was going on was wrong enough that I had a clear enough answer that I could step away?

I got into this because I didn’t feel like I had any outlets where I could be really open and vulnerable about what felt to me like the messy questions that I had never gotten to talk about with anyone. If I could change the world, it would be to make a world where people feel like it’s possible to be more open and that the people that they’re open with will be compassionate and that shame will not come into the picture.

The way that I left was to finally arrive at trusting my body enough, that it was telling me I couldn’t endure this anymore and it hurt. I had been ignoring myself for a very long time because I thought that this man knew me better than I did. Finally, the answer was just, I am right about me.

I would say to people, the best you can do is to just trust yourself. If it feels bad, step away and just try that out. If you feel like it’s going to be a disaster for you to leave, then that’s a pretty clear red flag that it’s not a good situation. You should be able to leave. That’s the best answer I can give to that, I think.