We are told that the world of work has been irrevocably changed for the better since the pandemic. No commute, working at a time that suits you and spending more time at home have all been framed as a "win for workers." Yet while flexible working certainly brings certain benefits, overhyping it comes with its own dangers, as its deployment has in some cases led to the undermining of working conditions rather than their enhancement. Perhaps the real question we need to be answering about the future of work is this: How can the embrace and further rollout of flexibility be a win for workers in a post-COVID landscape?

The idea of "flexible working" has a long lineage; its historical emergence can be traced back to liberal politicians of the early 2000s, who, in an attempt to create a more liquid market, realized nimble hiring and firing of employees would be better for employers. This new relationship between employers and their labor force was symptomatic of the non-interventionist labor market ideology of the neoliberal era. Promoted under the banner of "work–life" balance, the progressive ambition at its core is the idea that the time required for the job might fit around the demands of the employee's life.

Increasingly, however, rather than facilitating greater autonomy for employees, flexible working created the conditions in which the line between work and private life has become blurred. As management professor Almudena Canibano's research demonstrates, there is an opaque ambiguity that lies at the heart of flexible working: on the one hand, employees experience it as an employment perk that enables them to work in a more self-directed and autonomous fashion; on the other, the experience of flexible working requires being available outside working hours, working overtime and working wherever you are.

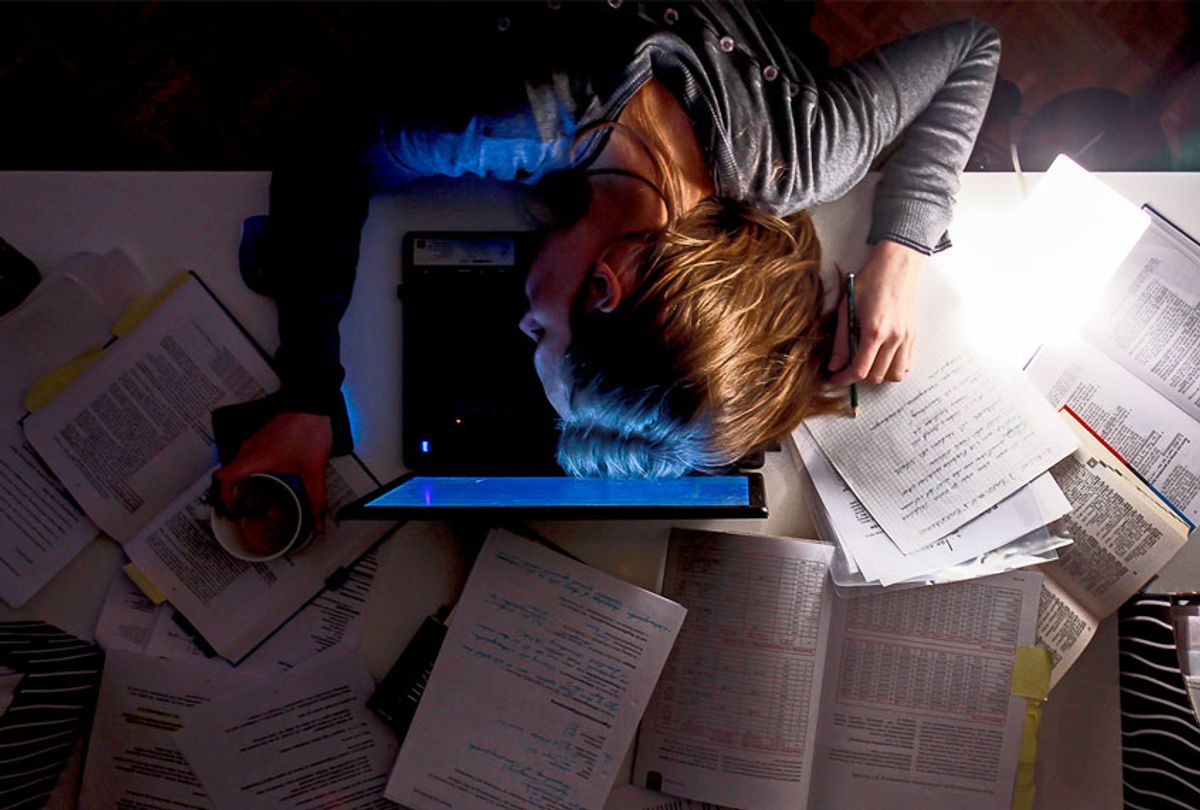

Where there is ambiguity, forces decide — and the past eighteen months have shown us how flexibility can be exploited by employers in order to create an "always-on culture."

During the pandemic the ability of white-collar sectors to work from home created the hope that a better world of work was emerging — one which would liberate workers from the arduous commute and the sterile monitored working culture of the office. That newfound optimism is, however, beginning to wane. From home surveillance to reports of increased burnout and mental health distress, the progressive aspirations of flexible home-working has, for many, turned into a culture of overwork that undermines workers' rights to decent hours and their ability to switch off from work.

In contrast to platitudes from CEOs about "work 2.0," the grim reality of "flexibility" in today's low-paid labor market is well-documented. Employers have used malleable "non-standard" contract terms, such as those with no minimum guaranteed hours (zero-hours contracts) and bogus self-employment, in order to be able to hire and fire individuals more easily — and thus avoid providing many of the benefits that employees on standard contracts enjoy.

In addition, women and ethnic minorities are overrepresented in precarious labour markets, making one-sided flexibility a race and gender issue. The caring professions in particular stand out for all the wrong reasons: in the UK, for example, 35 percent of care workers are on "flexible" zero-hours contracts. It is no coincidence that those working on flexible contracts pay wages that on average fall below the poverty line.

Flexibility for most low-paid workers over the last decade is not generally viewed as an employment perk; rather, it has often translated into an anxiety-inducing experience of living paycheck to paycheck.

If we are indeed to "build back better" after the pandemic and re-address the power imbalance that exists between employees and employers in today's labor market, we need to recognize that flexibility within the context of being overworked or underemployed is in fact faux flexibility. It is the mere illusion of control over your working time when, in reality, there is very little. To fight the spread of flexibilization — whether in the form of exploitative contracts or in the form of "always on" work culture — we suggest a different tact in our book.

Let's reconnect with the basic and transformative demand for more free time: that is, time away from our jobs, for ourselves. This was common sense for American workers from the Civil War right through Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal, when the forty-hour work week was put into legislation via the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Indeed, the weekend as we know it was created just after World War Two as the "new normal" in an increasingly mechanized workplace. Likewise, post-pandemic, in the context of widespread remote working tech, working people should demand freedom over flexibility, in the form of a shorter working week for the same pay. While we shouldn't dismiss the ways in which flexibility can be a genuine employment perk, we should aim higher when it comes to the future of work.

The shorter working week is no longer a "utopian" fringe idea; rather, it is a central aspect of the renewal of progressive politics that is taking place around the world. From the hugely successful public sector trial in Iceland, to the Spanish Ministry of Labour introducing a pilot subsidy scheme for companies wishing to pursue four-day weeks, these initiatives demonstrate the ways in which bold work time reduction schemes can offer workers new freedoms.

Of course the implementation of shorter working practices cannot address all the forms of inequality in one fell swoop: better wages, greater democracy in the workplace and decent holiday allocations are also good starts. However, at a time when labor shortages are increasingly being felt in the US and the UK alike, now surely is the moment for workers to fight for rights that enable not only freedom in work, but also freedom from work. In doing so, this would represent a true win for everyday people in a post-Covid era.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Shares