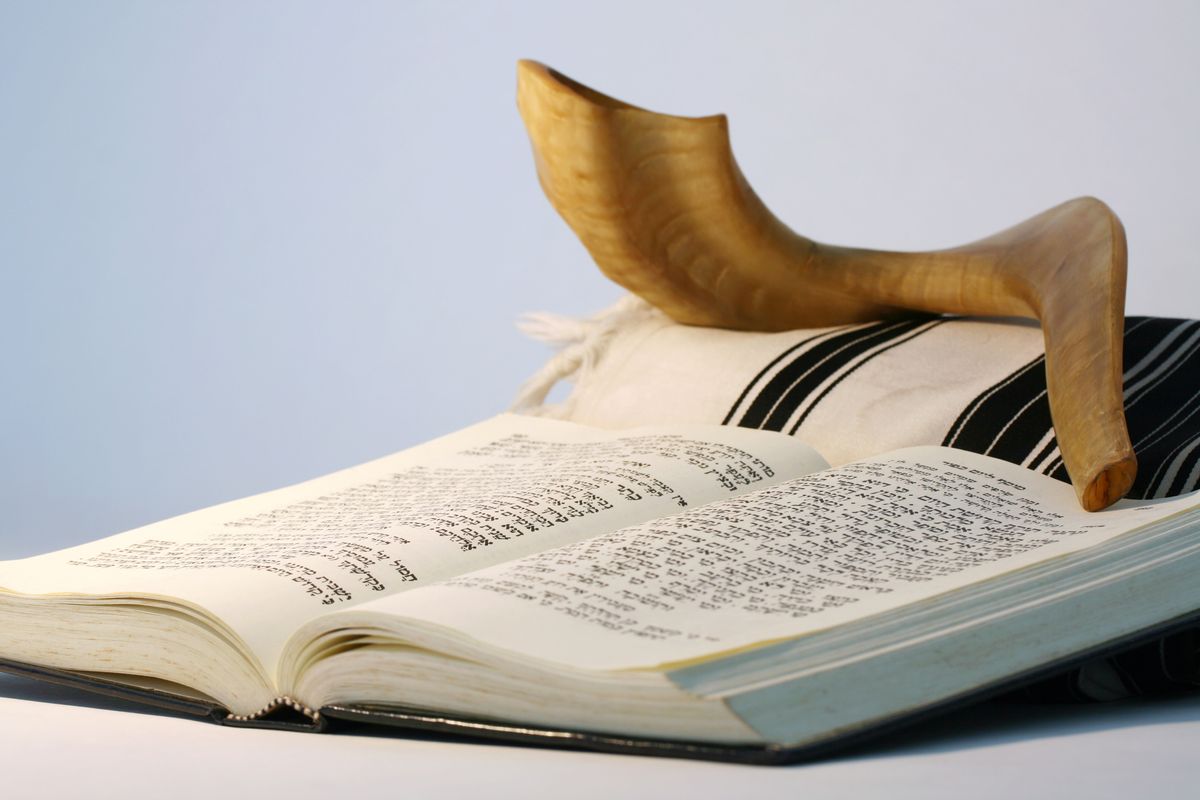

Yom Kippur, the holiest of all the Jewish High Holy Days, literally translates to "day of atonement." Jews throughout the world express remorse for both their individual sins and those of humanity by fasting, praying and focusing entirely on religious observance. For the spiritually vigilant, this process requires authentic humility, a quality described by the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides as the middle path between pride and shiflut, or "self-abasement."

Fasting and atoning can be profoundly spiritual experiences for many Jews who observe the religious holiday. Yet there is also a psychological and mental health benefit to embodying humility, as Maimonides defined it. Indeed, from both a mental health perspective and a social perspective, psychology research today affirms that humility is a trait with many personal benefits — on Yom Kippur as much as on other days.

"I think when a person is culturally humble, they are more aware of their limitations when it comes to their own cultural perspective and worldview," Joshua Hook, a psychology professor at the University of North Texas and lead author of the book "Cultural Humility," told Salon by email. "They understand that their own perspective is one way of viewing the world; it may not be the 'right' way or the 'only' way."

In other words, people who lack cultural humility are prone to being rigid in their perspectives and filtering out information that does not confirm their preexisting viewpoints. This can lead to decisions that harm not only others, but themselves — a moral that is particularly relevant in this drastically politically polarized moment.

The health benefits of humility

Noelany Pelc, an assistant professor of psychology at Marian University and co-author of an academic article on psychology and cultural humility, says that humility is essential for both social success and individual health. Cultural humility is a great example of a type of humility that accomplishes both objectives.

"While there are several dimensions of humility, including intellectual, relational, and cultural humility, it seems to center around a couple of themes: having an accurate view of ourselves (not better or worse), portraying ourselves accurately and modestly to others, and being other-focused," Pelc writes. "Essentially, humility allows us to be non-defensive, open, willing and interested in learning about and with others, without feeling threatened by perceived attacks to our sense of self."

The same principle applies to humility more broadly. It "is a good insulator to a tendency or desire to compare ourselves to others, or to compete with others," Pelc explained. "People who embody humility feel more at peace and satisfied with their own sense of self and identity, and are not as motivated to look for approval or admiration from others around them. In other words, humility allows people to remove themselves from harmful social competition and a fragile sense of self-worth or esteem."

Humility does more than simply prevent negative personality traits. It also strengthens interpersonal bonds because it allows individuals to better appreciate others' strengths and weaknesses, as well as in general behave in a more empathetic and helpful way. People who admit to their own limitations will be less inclined to focus on themselves and instead listen to others; they will also feel confident enough to assert themselves when the sentiment is justified and the situation calls for it.

"Openness, and willingness to learn makes humble individuals more effective problem solvers and learners, as they take in feedback and acknowledge their limitations," Pelc pointed out. "In general, acknowledging that there is much in the world that we simply don't know, allows us to be open to experiences that are different from our own."

So how does one draw a line between confidence and lacking humility?

"Healthy confidence is the knowledge that you have 'done your homework' in obtaining all relevant information and that you have logically, as objectively as possible, evaluated the information or data," David Reiss, a psychiatrist who contributed to the book "The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump," told Salon by email. "Having done so, you can then be confident – and you can assertively maintain and defend – that you have reached the most reasonable conclusion possible given the data available."

Humility adds an important caveat to that confidence, however. First, all information can be tainted by subjective opinions, and therefore even the most well-grounded research should still be open to debate, as long as the debaters are equally well-researched and act in good faith. Second, people who are confident that they are right in one moment should be flexible about later changing their mind based on new information.

"Changing one's assessment or point of view would not indicate that the initial assessment (or having had confidence in the initial assessment) was wrong at the time, but that you are not arrogantly/grandiosely tied to your conclusion if additional data or reasoning suggests a different perspective or alternative conclusions," Reiss explained.

Can you have too much humility?

Shauna Bowes, a research assistant and doctoral student at Emory University and co-author of an academic article about the relationship between intellectual humility and being susceptible to misinformation, explained to Salon that researchers are only starting to pay attention to the downsides of humility. Certainly people need to be aware if they are in abusive situations and not view standing up for themselves as arrogant or lacking humility.

"If in an abusive relationship for instance, one engages in humility to appreciate the abuser's perspective, then this may not be helpful and instead may be harmful," Bowes wrote to Salon. "In such a relationship, assertiveness and self-preservation are key."

Bowes added that race and sex also play a role in how healthy it can be to display humility. "It may be more costly for a woman or individual identifying as a racial/ethnic minority to engage in humility when they are in a subservient role (e.g., boss is a man or a White individual) compared with a man or an individual identifying as a racial/ethnic majority; again it may be more important in these relationships to practice assertiveness and prioritize the self."

She added that these downsides have more to do with specific contexts, however, than any inherent downsides to humility as a personality trait.

Humility is a particularly crucial trait on Yom Kippur in 2021 because of the very unique social and political conditions of this year. Americans are deeply polarized on COVID-19 vaccines, climate change, and racial justice. There is seemingly no visible end in sight to the bitter culture wars that have riven the nation.

"I think a lot of political polarization can be characterized by an absence of humility," Bowles observed. "As the late John McCain once said, 'Among its other virtues, humility makes for more productive politics. If it vanishes entirely, we will tear our society apart.' I wholeheartedly agree with this sentiment. If we go into a political conversation with 100% certainty that our views are correct, that there is nothing else someone can say to change our minds, and that you (rather than scientists) are the expert on the topic, then how does bipartisanship happen?"

Pelc elaborated on how this principle applies to how people are behaving during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Humility includes being compassionate to others, even when there is no immediate benefit to us, or social pressure to do so," Pelc wrote. "In many ways, it intersects with issues of social power, as prioritizing the needs of those who have less representation or who are vulnerable (e.g., children, older individuals, minoritized groups and immunocompromised individuals) requires us to value the welfare of others in a meaningful way."

In its own way, that scientific explanation is also the Judaic one. True humility requires both self-respect, so you can be healthy and happy, and self-awareness, so you will remember your obligations to society and to defer when necessary to people more knowledgable or skilled. Judaism teaches that every person is collectively responsible for all of humanity's sins, that the most virtuous person and the most vile share some level of responsibility for one another. While science does not offer moral arguments of any kind, the existing body of knowledge strongly suggests that this attitude toward humility is actually the healthiest one for everyone.

Shares