Face masks. Critical race theory. Bathrooms. Remote learning. Schools and schooling have become a flashpoint for America's culture war — for adults. But in actually talking to adolescents across the country, I discovered that grown-up fears and fury are disconnected from students' most pressing concerns.

Ariana Lemus, a 16-year-old from San Mateo, California, said she feels like a pawn: "Most of the problems that adults are talking about," she said, "it's a lot less important to us right now. They're saying, 'This is for the kids,' but they're not really listening to us kids."

She and her sister Karina, an eighth-grader, learned remotely all year last year. Because school days were shorter and it was easier to get distracted, Karina said, "We didn't get to learn as much as we could have." Ariana agreed: "I struggled a lot with turning things in on time. It didn't really feel like school." But this potential learning lost doesn't stress the sisters out.

"I have faith I'll catch up eventually," Ariana said, echoing Bradshaw Cuff Jr., a 14-year-old from Bowie, Maryland. As Bradshaw told me, "I don't think I really learned anything new, because the stuff we were learning is stuff that I had already learned in the past grade. And I lost a good amount." He feels for other kids that "are just falling behind and aren't where they're supposed to be," and sees that as a real, significant problem, but said, "It's not necessarily something I worry about, because I'm good at catching up very fast."

Ariana and Karina Lemus (Photo provided by the family)Relationships matter most to students

Ariana and Karina Lemus (Photo provided by the family)Relationships matter most to students

Bradshaw is more concerned about how disconnected he started to feel.

"My whole personality changed from being up and wanting to do a lot of fun stuff to being like, 'I'm just trying to chill.' I was probably three times less happy."

He prefers the old version of himself, and wants to feel motivated again.

"The students are a good reason that I want to go to school, that I enjoy going to school," he said. "So when I didn't really have social contact with all the students, I didn't really feel like paying attention." He kept in touch with close friends, but says he "kind of fell off" with everyone else. Making new friends over Zoom felt impossible.

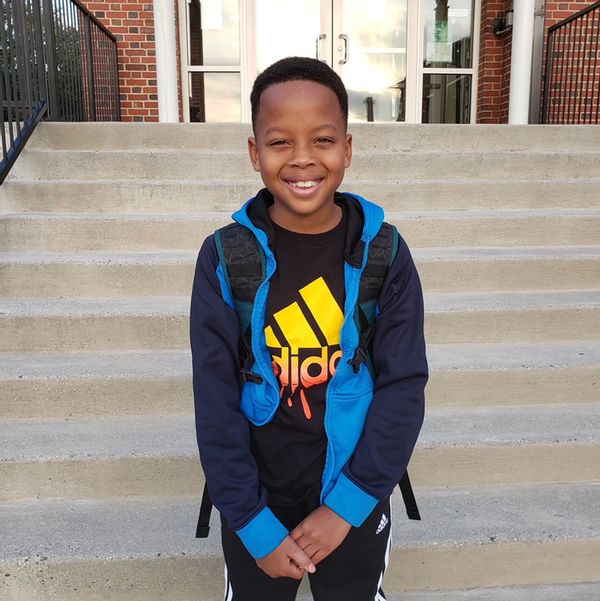

Bradshaw Cuff Jr. (Photo provided by the family)Eighth grader Leah Schneyer-VanZile has felt a similar sense of isolation this past year and a half. Though she had the option of hybrid learning, she ended up staying home all last year. Now, the 13-year-old from Arlington, Massachusetts said, "I can't wait to just be in school and have real classes and have a binder."

Bradshaw Cuff Jr. (Photo provided by the family)Eighth grader Leah Schneyer-VanZile has felt a similar sense of isolation this past year and a half. Though she had the option of hybrid learning, she ended up staying home all last year. Now, the 13-year-old from Arlington, Massachusetts said, "I can't wait to just be in school and have real classes and have a binder."

The hardest part of remote learning was not being able to develop relationships, she said.

"I couldn't tell you a single thing about a bunch of my classmates, because they didn't have their cameras on and they never talked," she added.

During class, Leah did connect with one kid in a breakout room. But they never could transition from friendly to friends. In ordinary years, Leah said she'd make that jump easily, saying to herself: "They're really nice. I'm going to walk to my next class with them." She often thinks about one day in sixth grade: "I was just walking out of the building to the bus, past my locker, just waving. 'Bye, so-and-so' and 'Bye, so-and-so.' And it was so nice. I'm not best friends with all of them, but I know them."

Leah Schneyer-VanZile on her fist day of 8th grade (9921) (Photo credit Carolyn Schneyer)Both Bradshaw and Leah put a finger on a phenomenon researchers call "weak ties," a happiness uptick humans experience from brief interactions with acquaintances. Close bonds are important, but these casual friendships are too, especially for adolescents who are developmentally primed to maximize social interaction and exploration.

Leah Schneyer-VanZile on her fist day of 8th grade (9921) (Photo credit Carolyn Schneyer)Both Bradshaw and Leah put a finger on a phenomenon researchers call "weak ties," a happiness uptick humans experience from brief interactions with acquaintances. Close bonds are important, but these casual friendships are too, especially for adolescents who are developmentally primed to maximize social interaction and exploration.

"My friend who was in hybrid [learning] was talking to me about this guy who asked her for her Snapchat," Leah said, "and she was like, 'His friend came up to me and whispered, because he was really nervous.' I didn't get any of that. I want to have a crush again."

Child after child told me this was what they missed most about going to school: relationships.

With teachers too. They think teachers generally worked hard and most said they believe their own teachers truly care. (If they'd heard about tensions between some parents and teachers' unions, they didn't let on). But it isn't just other students they want more access to and attention from.

Sullivan Davis said he'll now never take for granted cooperative learning opportunities and being able to raise his hand in class. As the Durham, North Carolina eighth grader told me, "It was mostly just 'learn this, show that you learned it, move on' type of assignments. It was so dull." He felt anxious and frustrated when he tried his hardest and would still "mess up" because of software issues that teachers could have easily sorted out in person.

Aiden Cuff, Bradshaw's younger brother who is starting sixth grade, said of distance learning: "You can never tell the teacher if you're going through stuff." He rated his happiness level during the pandemic at "zero" and said now that he's in school he feels "super relief."

Aiden Cuff (Photo provided by the family)But not everyone studied from home last year. Liv and Elin Hendrickson attended school in person in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. After a few months at home with "workbooks and online assignments" in the Spring of 2020, Liv noticed a big difference upon returning to campus last Fall. "It's easier for me to concentrate if I'm around my friends," she said, "and if I need help with something and the teacher's busy helping someone else, I can be like, 'Hey, can you help you with this one thing?'"

Aiden Cuff (Photo provided by the family)But not everyone studied from home last year. Liv and Elin Hendrickson attended school in person in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. After a few months at home with "workbooks and online assignments" in the Spring of 2020, Liv noticed a big difference upon returning to campus last Fall. "It's easier for me to concentrate if I'm around my friends," she said, "and if I need help with something and the teacher's busy helping someone else, I can be like, 'Hey, can you help you with this one thing?'"

Where they live, remote learning is more of a doomsday scenario. They even have what Liv called "online days" at school akin to a fire drill. For a few hours, "we have to basically pretend like we're online," she said. If they have a question for their teacher, "We have to email them and message them online."

Masks and gender-inclusive bathrooms don't need to be a big deal

Masking is optional there, and seventh grader Liv said, "It's a little weird to be only one out of a few people wearing masks in your classes. Some of our teachers do, but not all of them."

This lack of uniformity impacted her sibling's ability to focus. Elin, who's in sixth grade, said, "You're not really thinking about, 'Oh, what is this assignment today?' You're just kind of thinking, 'Do these people have COVID?' It's scary to change classes every 45 minutes, being unvaccinated and knowing there's definitely a few people in here that have it. But I am still glad I am not remote."

Further demonstrating that "back to normal" policies had their own challenges for kids, Elin had to drop out of extracurricular activities with too few safety precautions. "I always felt really down and sad when I had to miss things," Elin said.

Liv and Elin Hendrickson (Photo credit Christine Hendrickson)Liv isn't as anxious since she's vaccinated now, but chimed in, "If wearing a mask for seven or eight hours a day might stop the pandemic, I don't think that's too much to ask."

Liv and Elin Hendrickson (Photo credit Christine Hendrickson)Liv isn't as anxious since she's vaccinated now, but chimed in, "If wearing a mask for seven or eight hours a day might stop the pandemic, I don't think that's too much to ask."

And that was these kids' refrain: Masks are annoying, but they're not terrible; and if they are (or even might be) effective, why waste energy arguing about it?

Nadia Fox, an eighth grader from Coppell, Texas said, "It doesn't feel like a very big deal at all. It's just something really small, and it's meant to help a lot of other people." Ariana agreed: "It's a bit of a pain to wear it, but just going through the halls from class to class, it's really crowded so I feel like it's necessary." Leah went to camp over the summer. She said, "By the first day, I'd forgotten that I was wearing a mask. I tried to drink water through it! It's not that big of a deal. You get used to it."

Even though Sullivan wears glasses and "gym class sucks with masks," he said, "It's fine," and a small price to pay: "I have never been so excited to end summer break in my life," he added, "My mom was surprised."

Like other kids in schools with mask mandates, Bradshaw doesn't understand the fuss: "It's not going to harm you. Just wear your mask."

The students I talked to who come from communities where masks aren't the norm have classmates who've decided not to wear them, but they said even those kids don't seem riled up about the issue.

The same general attitude applied to gender-inclusive bathrooms.

When I asked Leah whether her school has them, she paused: "It took me a second, because I haven't been there in awhile." But it did, the eighth grader soon remembered: "I'll use the female restroom, because that's what I feel is appropriate for me. You can go in whatever bathroom you want to. I don't care."

Sullivan Davis (Photo Credit Sara Lachenman)Sullivan said the same stance reigns at his school. "Students don't care…. If you're a boy and you feel like you want to be a girl, then no one's going to stop you walking into the women's bathroom." When it comes to the gender-neutral bathroom at Bradshaw's school, he said, "Everybody really respects it. They're fine about it."

Sullivan Davis (Photo Credit Sara Lachenman)Sullivan said the same stance reigns at his school. "Students don't care…. If you're a boy and you feel like you want to be a girl, then no one's going to stop you walking into the women's bathroom." When it comes to the gender-neutral bathroom at Bradshaw's school, he said, "Everybody really respects it. They're fine about it."

Elin, from South Dakota, said their school doesn't have gender-neutral bathrooms, but, "I would really like that, as a gender fluid person, because sometimes you feel different on different days — like a girl sometimes, like a boy sometimes, and sometimes like a non-binary identity — so I feel like it would be important to just feel a little bit safe."

Leah was more forceful: "I think it's ridiculous. Why do you care what bathroom another child uses? It has nothing to do with you. It's not going to make your child uncomfortable, and if it does then your child needs to think about what it feels like to those other people having to go to a bathroom that doesn't represent who they are."

They want to talk about race and racism

"So when I first heard about critical race theory," Sullivan said, treating the complex academic approach as simply "talking about racism" like most Americans these days, "I'm pretty sure it was in my social studies class. And we were online and as soon as the teacher told us what people were saying, every kid in the class was like, 'What? Are you kidding me? Like, if a country can't own up to its mistakes, it sucks."

Here too, Leah had an opinion: "I think that race should absolutely 100% be discussed in schools. If you're white like me and you grew up in a primarily white town, you're kind of sheltered from having to think about race. And then all of a sudden they're hit over the head with Black Lives Matter protests. And you just kind of realize that your experience isn't like what other people have experienced. I was just shocked."

Ariana focused on how engaging the topic is: "There's usually a disconnect with the past. You don't really think of people in the past as people. But this will help be like, 'No, they really were people and those issues at the time, they were really real,' and the more in-depth we learn about it, the more we just learn."

"Especially in South Dakota," Liv said, "because the history of South Dakota is a lot of Native American stuff, and there's no other way that you're going to learn about it, except maybe your parents telling you."

Where Nadia lives in Texas, she says that "the mayor and the social studies teachers still want to continue teaching about the history behind it all and how it formed our society and how it's still going on, but there's a lot of laws being passed and some of the people in my area support them." She said adults around her are "trying to tone it down or sugar coat it away from the kids, but it's not really helping, especially whenever the kids are the ones who are trying to bring up the issues."

Nadia Fox (Photo Credit Jonathan McInnis)That was another common thread in my conversations. These students feel capable of engaging in nuanced discussions and approaching fraught topics with care — even if today's politicians don't seem to think they can handle it.

Nadia Fox (Photo Credit Jonathan McInnis)That was another common thread in my conversations. These students feel capable of engaging in nuanced discussions and approaching fraught topics with care — even if today's politicians don't seem to think they can handle it.

"Kids should have a lot more say in what's being taught to them," Nadia said, "and whenever things are glossed over, I feel like the kids should be able to be like 'Hey, wait, that's not accurate at all. What about this?'"

Leah drew a parallel to health education. "My PE teacher showed us the video on why they originally created JUUL pods. The entire curriculum was, 'Don't JUUL. JUUL will kill you.' And he showed us this video that said they originally created it to help people ease off smoking addictions. And I was like, 'That's actually really cool.' It's horrible that they appeal to teens now, but it's really interesting that it started with this good purpose."

When it comes to trusting adolescents to hold multiple truths at once and think critically, she said, "I wish they would do more of that."

Grown-ups don't seem to be talking about the issues that matter most

But the most important thing to these adolescents wasn't what adults are talking about in the wake of distance learning; it's what they're not talking about. Relationships were their number one priority, but they raised a bunch more, some of which surprised me.

A concern that came up repeatedly? Making more free time and feeling less stressed about tests.

During the pandemic, Nadia said, "I was able to take more time to myself and figure myself out more." She thinks kids her age need more agency in deciding how to fill their time. Bradshaw didn't stress over homework as much during lockdown, "because I knew once I finished it, then I don't have to really do anything else," he said. And Leah liked being able to just sit and listen to music. When I started to say goodbye to Aiden, he stopped me. "You know what you should put on the news?" he said: "Kids need more video game time after school."

They could use less pressure around tests as well. Leah said when it comes to Massachusetts state testing, "They really pushed that one. They basically tell you, 'You need to be stressed.'" But other kids, like Nadia, felt test anxiety all year round. End-of-grade tests in Durham and even missing classwork and bad test grades ultimately didn't count last year, Sullivan said, but because no one told him that up front, he felt pressured.

The older Ariana has gotten, the more worried her classmates have become around testing and college admissions.

"A lot of people are especially stressed out about the SATs, because it really can impact where you go to college, and if you're going to get in at all." She said teachers and parents haven't directly told her it's a high-stakes situation, "but they don't really need to, because we already know how much it can matter." It doesn't really help when colleges make submitting SAT scores optional, she said, because they'll assume "if you didn't put the test on, it meant you didn't do good," but she's felt some relief from the University of California system refusing to look at SAT scores altogether.

Teaching practical skills and making learning fun

"I think the biggest class that I did fall behind on was PE," Karina said, "Now, we're doing volleyball, and I find it really fun." Milo Evans from Walnut Creek, California is also a big fan of PE, especially experiences like dodgeball and capture the flag.

One of the saddest parts of the pandemic, he said, was trying to hold band practice over the internet: "We couldn't all play at the same time because the Zoom glitched out so everybody just played muted." You might be tempted to write off Milo's suggestions for enhancing extracurricular opportunities as a less mature take, but that would be a mistake. "The thing they should be mainly focusing on is how happy the kids are at the school," Milo said, "because if the school is fun, then they will want to go to school." He said the same thing goes for assignments: the more topics and tasks appeal to kids, the more they'll learn.

Milo Evans (Photo credit Katie Evans)Leah wants adults to shift their concern to "the lack of teaching of how to do actual things that you need in life." She said she can write a five-paragraph essay, "but I couldn't tell you how to open a bank account. I have no idea how to put a lease on a house. I don't know how to register for a credit card." She'd like to see her school's family and consumer science class enhanced and expanded.

Milo Evans (Photo credit Katie Evans)Leah wants adults to shift their concern to "the lack of teaching of how to do actual things that you need in life." She said she can write a five-paragraph essay, "but I couldn't tell you how to open a bank account. I have no idea how to put a lease on a house. I don't know how to register for a credit card." She'd like to see her school's family and consumer science class enhanced and expanded.

Ariana agreed. "A lot of the complaints I hear, especially from my friends, is that we're not going to use this stuff in real life and we're wasting some of our time on subjects we're not going to think about." She wants to see more of a focus on current events and culturally relevant materials. Subjects like media literacy, she said, should get much more attention.

Prioritizing equity and mental health

Ariana also said if adults were talking about equity during the pandemic, they weren't doing it loudly enough.

"If your house is a lot quieter and also your internet was better, you have a computer, it all really impacted how well you did or even just how easy you could focus." (Milo and Aiden also raised the issues of Zoom failures and having to work with a sibling nearby.)

With in-person schooling, Ariana said, students come from different backgrounds and circumstances that make it easier for some to concentrate than others. But the physical space of the classroom is at least the same, removing one layer of inequity. And she says her friends have benefited from being able to access free lunch without filling out forms. Still, she wants to see more progress and more discussion of what progress would look like.

Nadia and Leah both agreed that oppression and biases aren't topics that should be raised in a humanities class and then never brought up again. They want adults to get as fired up about educational equity as they have about mask wearing.

Multiple students mentioned the value of school-based relationships in preserving and improving mental health. They also largely appreciate their schools' attempts at social-emotional learning, even if that's a term some adults find off-putting. And they want more of it all. Leah said, "It definitely needs to be something that's talked about and normalized more in school. You don't need to be scared to tell somebody that you're anxious or stressed. It shouldn't be a stigma."

Kids are tired of the fighting

One more thing was clear: Kids are over our drama.

Liv said, "In person, I haven't really seen most people get into a really huge debate, but I've definitely seen it more on social media, because people are more bold behind the screen." And she's sick of it.

Elin chimed in, "The world isn't big enough for everybody's argument. If we can just try and get along, we'll make school better for everyone."

This frustration with their elders — not necessarily those around them, but with the arguments they've watched unfold on the news and in TikTok comment sections — surfaced repeatedly.

"The fighting with adults is ... I don't know," Karina sighed, "It's mostly pointless just because of the topics. They need to start working together, because we do have some really big issues right now. . . like climate change is a big one for me."

From Texas, Nadia concurred. "I feel like they should maybe stop arguing with each other and see what the younger generation has to say about it, since they're the ones who are being impacted the most."

Shares