Decades before Zac Efron portrayed notorious serial killer and rapist Ted Bundy in 2019’s “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” Leonardo DiCaprio was being considered for the role of a man named Billy Milligan. In 2015, the year after Milligan’s death, DiCaprio was again set to play the man accused of rape and possible killer in a screenplay called “The Crowded Room,” though the project has yet to materialize.

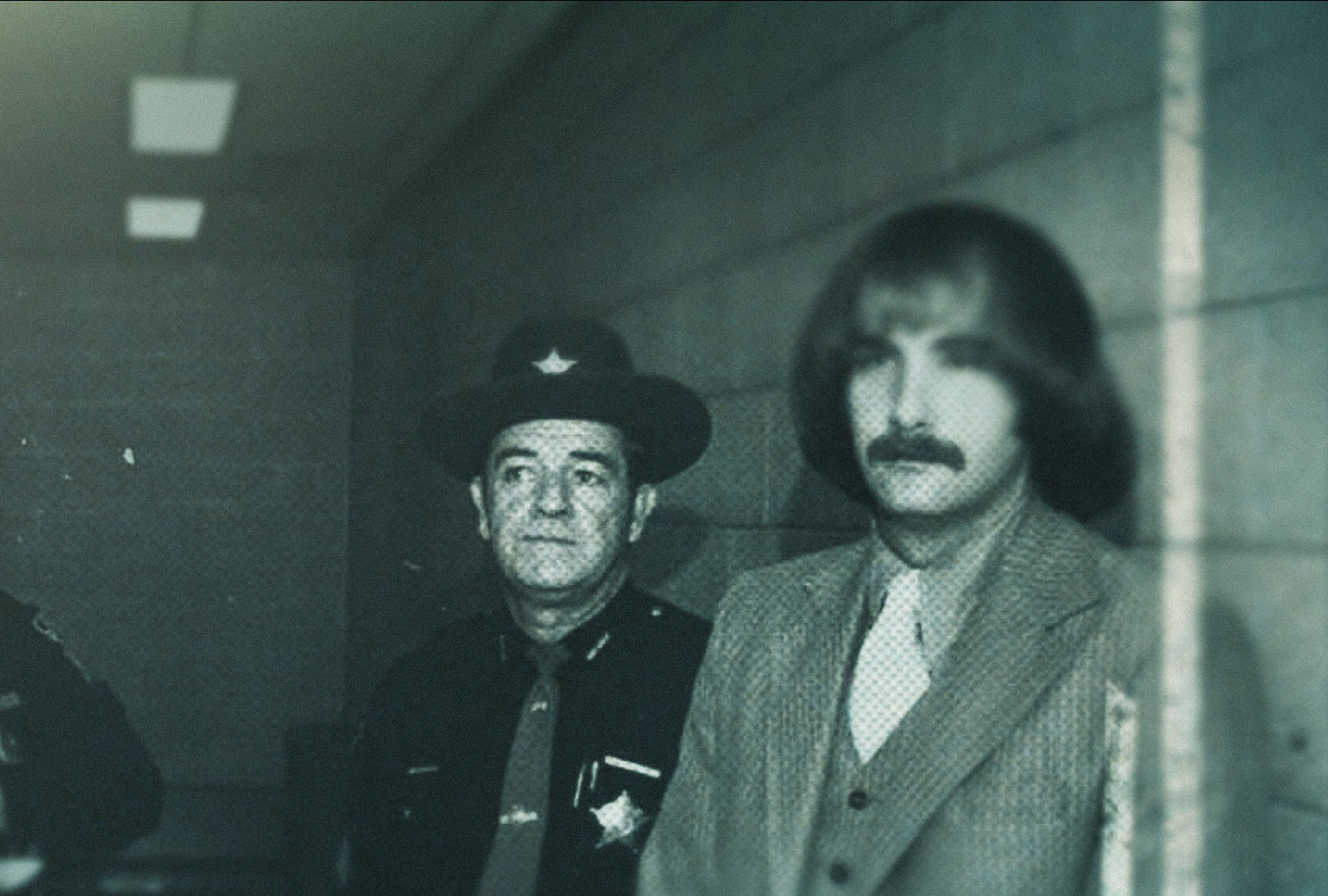

Where Bundy is a household name, something of a celebrity and even a twisted sex symbol, Milligan might just eclipse him, with “Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan” now streaming on Netflix. The four-part documentary series presents the fascinating, horrific and outrageous story of Milligan, an Ohio man who was accused of kidnapping and raping three female college students in the 1970s. Milligan claimed he had multiple personality disorder, and that one of his 24 personalities was responsible for the alleged kidnappings and rape without his knowledge or control. As a result, he was acquitted of these crimes because of an insanity plea.

Today, he remains practically absolved of the crimes he’s confessed to, as he emerges as something of a rockstar via projects like “Monsters Inside.” Through these stories, Milligan is elevated from a man some call a rapist to cultural legend, while his victims are buried. Notably, none of them or their family members are featured in “Monsters Inside,” as it instead pores over every detail of Milligan’s life.

As the documentary takes place 40 years after the alleged rapes, director Olivier Megaton told Salon the production had contacted and tried to include the victims – but many were either dead or unreachable. Still, there were certainly other ways the docuseries could provide care, focus or screen time to the impacts of sexual violence, but we see little to none of that. We’re instead treated to an onslaught of sometimes warm reminiscing and jokes that humanize Milligan, a man accused of tormenting women, who are treated as a footnote in the greater story.

Similarly, both Bundy and Milligan are already beneficiaries of white, male privilege. Their escapes, and their ability to at different times evade arrest and imprisonment from our racist criminal justice system by not appearing “dangerous,” are directly owed to their whiteness. And today, their places as seductive cultural icons who supposedly charmed their female victims are owed to their whiteness, too. The documentary further amplifies this privilege, once against spotlighting the perpetrators of violence . . . to what purpose?

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Throughout “Monsters Inside,” even after Milligan admits to the crimes yet was acquitted, we watch him live some semblance of a normal life between confinement in varying mental institutions. He continues to have sexual relationships with staff and visitors, even having a wedding ceremony with one woman at a facility, and continuing to date women throughout his life. At one point, he easily escapes an Ohio facility to start a new life in Washington state with the help of a man named Jim Murray.

In the series, Murray fondly recalls his experience aiding the dangerous man’s escape from a mental facility, as if it were a run-of-the-mill buddy road trip. While in Washington, evidence strongly suggests Milligan killed a missing man named Mike Madden. Still, years later, Milligan gets the celebrity treatment, is flown out to Los Angeles by filmmaker James Cameron, who was interested in making a movie about Milligan’s life, and even meets stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito. One of Milligan’s friends recalls visiting him in LA, as he lived a lavish, “high roller” lifestyle, according to the documentary.

Beyond Milligan’s treatment as a Hollywood star — a feat not even Ted Bundy could brag about — “Monsters Inside” is rife with interviewees with predominantly positive or highly sympathetic words to say about Milligan. Memories from Milligan’s brother and sister portray an unfairly maligned, misunderstood man, a humorous uncle, a genius artist.

Those who do acknowledge that Milligan had harmed others, treat these acts as tangential, unimportant. Murray, who seems to have faced no consequences for helping Milligan escape, also recalls directing a local play in Ohio, and casting his pal for a part.

“People only knew Billy as a rapist,” Murray says, explaining his casting decision as a way to show people “another side” to Milligan.

In contrast, only one FBI agent is brutally honest about his disgust with the media treatment of Milligan, saying “no one cared about Billy’s victims.”

“Monsters Inside” is a sprawling project of bothsideisms about the supposed duality of a man who admitted to rape. One woman who had dated Milligan and was interviewed by the documentary recalls a night on which Milligan swore he would kill her, prompting her to seek the protection of her brother. Shortly after, her brother says in the documentary that Milligan called them, alluding to having killed Madden in Washington, and saying he could kill both of them without consequence “because of his mental illness.”

To be clear, the documentary hardly seems supportive of Milligan, but its neutrality and significant screen time devoted to friends and family who are ambivalent about the rapes comprise yet another example of the true crime genre’s callousness toward gender-based violence.

There may be many literal sides and personalities to Milligan, but why does that matter? While this is certainly a fascinating legal case study, why should we care about him, or how “complicated” he was, more than we care about the women who say he harmed them? Or more than we care about sexual assault victims, in general?

Much of the first two episodes of the docuseries focus on questioning whether Milligan’s multiple personality disorder is real, implying the existence of personality disorders is somehow still up for debate in 2021. Or, specific to Milligan, the debate suggests that his violence is excusable based on whether or not he’s “faking” his condition. But truthfully, having multiple personality disorder doesn’t absolve rape, and nor should we implicitly suggest violence is innate to and therefore excused by personality disorders and mental illness.

Billy Milligan’s story is undeniably the sort of material that Hollywood and the massive, multi-billion-dollar true crime industry subsist on. But in our consumption of these wildly popular tales, we become desensitized to horrific crimes. And it’s through this desensitization, this obsession with stories of people we’ll never know, that violent men become legends and household names, while their victims and the traumas of sexual violence are all but erased.

“Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan” is now streaming on Netflix.