What makes a family, a family?

From acclaimed director Ry Russo-Young ("Before I Fall"), HBO's three-part documentary "Nuclear Family," explores this and other questions by excavating her own family's unique, transformative story, which remains a watershed moment for LGBTQ people and families to this day.

Russo-Young was born to lesbian couple Sandra Russo and Robin Young in 1981 by way of a sperm donor. At the time, queer couples still faced significant prejudice, and queer couples having children were an unheard of phenomenon.

"Being gay meant you were not going to have children," Young says in the series. "It was like you were giving up that right to have a family."

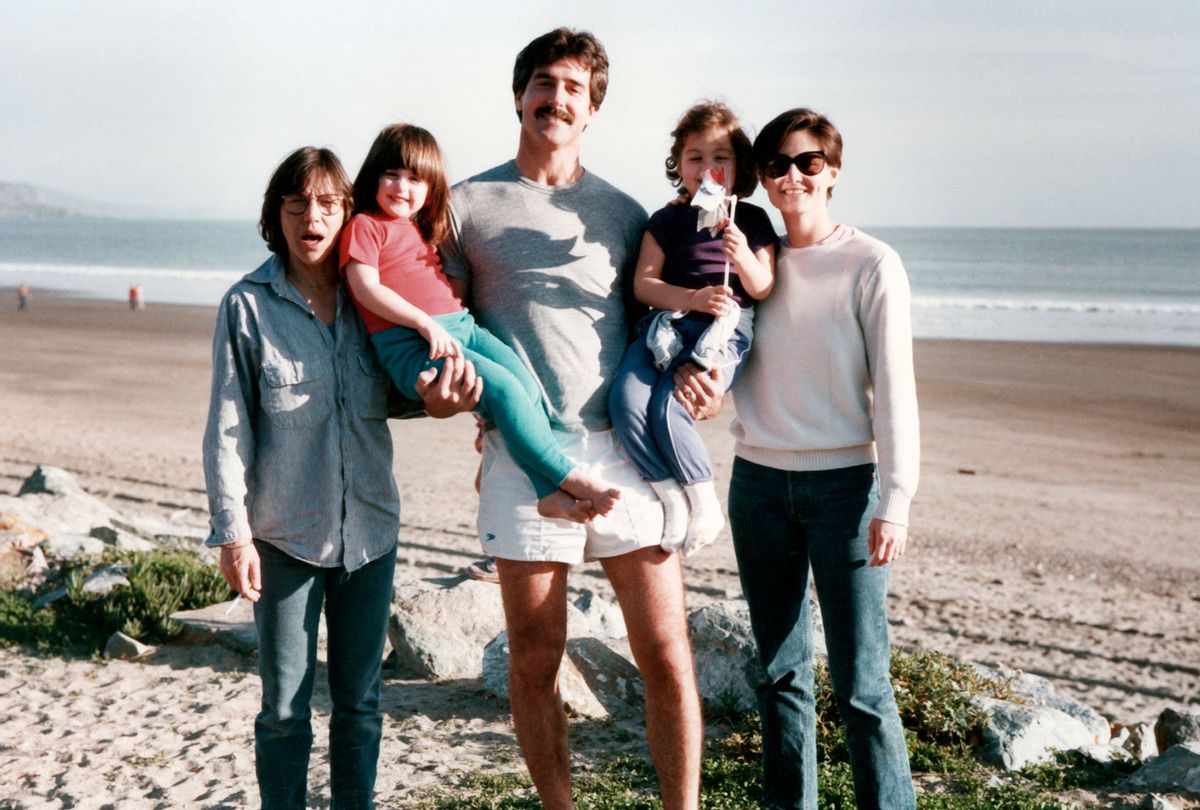

Nonetheless, Russo-Young and her older sister Cade had an idyllic childhood brimming with love — maybe even "too much love," Russo-Young suggests at one point. Everything changes when Ry's sperm donor, Tom Steel, develops such a strong attachment to her that he sues Robin for parental rights in 1991. The lawsuit sets in motion a cultural debate about what defines family and parentage at a time when same-sex marriage was a distant fantasy, and archaic notions of "family values" condemned father-less families like Ry's.

On a recent panel before the Television Critics Association (TCA), Sandra Russo recounted how Steel, a gay man and lawyer for LGBTQ rights, had capitalized on these sexist, heteronormative family values to gain access to Ry.

"Mr. Steel raised that argument, 'Well, it's always in the child's best interests to have a father,'" Russo said. "And [Ry] was seen as illegitimate unless he was in fact recognized as her legal father. That would cure her illegitimacy."

According to Russo, "The whole focus of the [lawsuit] was the nuclear, heterosexual family."

"That was the norm and that was the desired norm," she said. "And anything outside of that could be deemed harmful to the child or not in the child's best interest."

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Custody battles involving heterosexual parents have often gone down a simpler route, typically favoring mothers who are the primary caretaker. But Steel's lawsuit against Young exposed the lack of legitimacy and legal rights that same-sex couples and their families had, without the legalization of same-sex marriage.

Russo-Young notes that despite how both of her parents were her mothers, that was actually a "disadvantage because a lesbian couple wasn't recognized as a legitimate family." Steel had previously agreed with Young and Russo that he wouldn't be a part of their family, meeting the terms they said to be the sperm donor. But when he changed his mind, his biological role in Russo-Young's conception and dated notions of biology as foundational to the nuclear family offered legal grounds for him to threaten to upend Young and Russo's family as they knew it.

"There was the power of DNA, biology, which the court and the world at that time thought was all-important," Russo-Young said. "And then there was also some misogyny which was just in the world also and therefore in the courts, so both were functioning together."

Russo agreed that "biology sort of trumped everything else," acknowledging that despite the horrors of the HIV/AIDS pandemic that was so devastating to gay men in the '80s and '90s, Steel and other gay sperm donors like him would still be at an advantage in lawsuits like theirs. "If a gay man was a donor and in a dispute with a lesbian couple or a single lesbian mother, the law recognized that relationship over any other partnership or non-biological family member," Russo said.

Russo-Young told reporters that today, despite the challenges that remain for equality for queer and trans people, marriage equality has been pivotal to protecting LGBTQ families. "The fact that gay people can get married now . . . means that they are recognized as legal families. That fact allows them protections that my moms didn't have back in the day," she said.

"Nuclear Family" is strikingly powerful, interwoven with Russo-Young at different times in front of and behind the camera, as she interviews her family, her parents' friends, and even the lawyers who represented her sperm donor in the legal war he waged on their family. The process of creating the documentary required Russo-Young to push herself to go to places she hadn't before, including going through the many home videos of her and Steel, which she had first been given in her early 20s.

"I watched about a minute of those tapes and then put them away for many, many years and didn't look at them," Russo-Young recounted. "And it wasn't until I was in my mid-30s when I was thinking about making a movie that I took them out of the closet again."

Talking to those who testified on Steel's behalf during the case was also fascinating to Russo-Young. "None of them had a change of heart" since the lawsuit, but doubled-down on their beliefs.

"Everyone that I interviewed on 'Tom's side' was so specific in their beliefs, and was really trying, I felt, to still change my mind and to have me see it from Tom's perspective," she said. One of Steel's friends told her, "I've been waiting for you for 30 years to come and talk to me and I'm so glad that I can tell you everything I have to say."

Riveting and emotional as "Nuclear Family" in documentary form may be, Russo joked to TCA critics that her daughter deciding not to tell their story in a narrative, dramatized format had actually disappointed her and Young.

"We had a whole list of people that we thought should play us," Russo said. "Angelina Jolie was up there, you know?"

"Nuclear Family" premieres Sunday, Sept. 26 at 10 p.m., with new episodes the following Sundays.

Shares